Amanda St. John is one of thousands of Mainers carrying heavy college debt.

The 32-year-old York native studied for several years at Goddard College in Plainfield, Vt., earning a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts and completing two years toward a master’s degree in medical sociology.

After defaulting on more than $98,000 in student loans, St. John consolidated her debt and now makes $20 monthly payments that don’t even cover the interest, she said. She struggles to make larger payments, working part time at the Greater Portland Convention & Visitors Bureau in Portland.

Her college debt casts a shadow over her vision of the future.

“My credit is so bad,” she said, “I can’t conceive of buying a car or a house or even having a family.”

College debt is a hot topic right now, as high school seniors and their parents pick schools and arrange financing — a daunting task in a state that has one of the highest student-loan burdens in the nation.

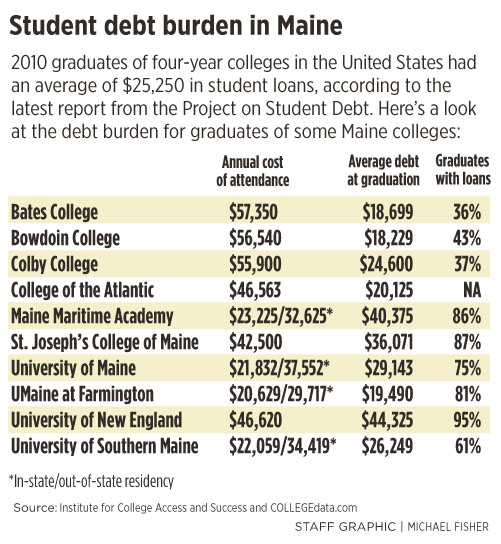

College seniors across the United States are preparing to graduate into a tough job market with an average of $25,250 in student loans, according to the Institute for College Access & Success, pushing the nation’s college-debt total beyond the $1 trillion level reached late last year.

President Obama shined a spotlight on the student-debt crisis last week while campaigning at several colleges across the country, including during an appearance on NBC’s “Late Night with Jimmy Fallon.”

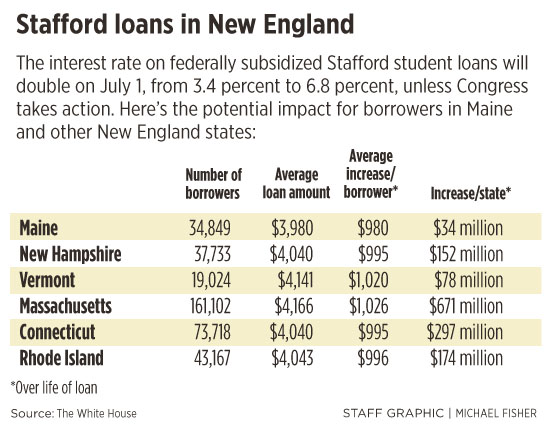

Obama called on Congress to block a July 1 interest-rate increase on federally subsidized Stafford student loans. The rate would double from 3.4 percent to 6.8 percent, affecting more than 7.4 million borrowers nationwide and adding about $1,000 in interest to individual loans averaging about $4,000.

On Friday, the House passed a controversial Republican-sponsored bill that would prevent the rate from doubling for one year and cover the $6 billion cost by eliminating preventive health care funding provided under the Affordable Care Act.

Obama has promised to veto the House bill. In the Democratic-controlled Senate, Majority Leader Harry Reid has proposed an alternative bill that would finance the measure by raising taxes on some high earners.

“Students and their families could owe thousands of dollars more starting this summer if we don’t do anything to stop a doubling of interest rates,” U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree, D-1st District, said Friday, before voting against the House bill.

LOW WAGES MAKE PAYBACK TOUGH

Maine’s college-debt load ranks No. 2 in the nation, after New Hampshire, according to the institute’s Project on Student Debt report released in December. The sixth annual study found that students who graduated from four-year colleges in Maine in 2010 had an average of $29,983 in student loans, more than 15 percent above the national average.

Sixty-eight percent of Maine’s graduates that year had student loans, putting the state’s proportion of graduates with college debt at No. 7 in the nation, according to the report. The study found high-debt states concentrated in the Northeast and Midwest, with wide variations among states, colleges and even campuses.

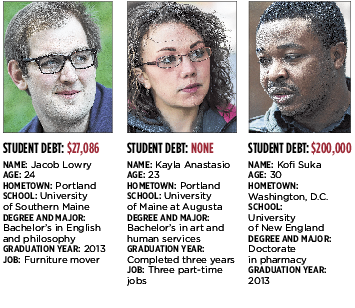

Jacob Lowry and other Mainers say they can’t afford to pay more for college loans.

Lowry, 24, is a junior at the University of Southern Maine who is studying English and philosophy. On Wednesday, he attended an Occupy Maine demonstration against student debt that was held in Portland’s Monument Square.

Lowry said he already owes more than $27,000 in student loans and worries that he won’t be able to find a job after graduation that will pay enough to cover his college debt and other expenses. While he’s in school, he’s working for a furniture-moving company.

“Student debt is so much a part of everyone’s life,” Lowry said. “We’re told to go to school and study what you love and there’ll be a job waiting for you when you get out, but increasingly, that’s not the case.”

Even college students who look forward to high-paid jobs after graduation worry about the impact of rising student debt.

Kofi Suka, 30, is a third-year pharmacy student at the University of New England in Portland. A native of Ghana, in West Africa, Suka is now a U.S. citizen who lives in Washington, D.C., when he’s not attending UNE.

Suka earned a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry on scholarship at George Mason University. He expects to have about $200,000 in student loans when he graduates from UNE next year.

He could make as much as $120,000 per year as a retail pharmacist, he said, but he’ll have to buy professional liability insurance along with paying other living expenses.

“I’m not a billionaire’s son,” Suka said. “If you’re not wealthy, you pretty much have to borrow money to pursue your dreams. But if you don’t choose a reasonable means of making a living, you run the chance of defaulting on your loans.”

Given the rising cost of higher education and student debt, Suka wonders if some people may avoid going to college for lower-paid professions and instead settle for jobs that don’t pay much but allow them to live comparatively debt- and stress-free lives.

“If the cost of college is more than I can afford, I might just as well take an ordinary job and enjoy life,” Suka said.

Tony Thompson, 38, graduated from the University of New England five years ago with a master’s degree in social work.

He works as a social work clinician in Portland. He has $97,000 in private student loans, which is a substantial debt since the military paid for his undergraduate degree.

“It’s a hardship with a mortgage and car payments and all of our other expenses,” said Thompson, who lives in Saco. “I always pay what I can, even if it’s only a little. I stay in contact with (the loan company). They’re pretty understanding. They just want their money.”

CONSULTANT: ANGER IS OVERBLOWN

Fear of college debt led Kayla Anastasio, 23, to attend the relatively affordable University of Maine at Augusta, where tuition and fees are $7,448 per year for state residents. She has completed three years toward a bachelor’s degree in art and human services, hoping to one day work in art therapy.

A Rumford native who lives in Portland, Anastasio said she has no student loans. She prefers to work while going to school and save money for tuition and books. She currently has three jobs: restaurant server, call-center operator and assistant to a disabled person.

“I’m not content unless I have at least two jobs,” Anastasio said. “I like to stay busy. I haven’t taken out student loans because I don’t want to be paying and paying and paying. But I understand if people don’t have the will or ability to do it on their own.”

Anastasio understands because she’s thinking about finishing her degree at the Maine College of Art in Portland, where the cost of tuition, fees, room and board exceeds $40,000 per year. If she does, she’ll probably have to take out a student loan to pay for at least part of it.

“It’s a big decision,” Anastasio said.

Gary Canter agrees with Anastasio. He’s a former high school guidance counselor who has worked as a college placement consultant in Portland since 1995. He says the current controversy over student loans is political “hype” and that anger over the college-debt crisis is misplaced.

“Student loans are not the problem,” Canter said. “You need to choose a college you can afford,” balancing budget against wants and needs.

When someone defaults on student loans, Canter said, “almost always a mistake was made (in choosing a college) and information was lacking from the start.”

Prospective college students and their parents must do their homework, Canter said, and know the difference between reasonable and irresponsible debt. Once they figure out what their “expected family contribution” will be, they should press colleges to make up the difference in financial aid.

“It’s a buyer’s market,” Canter said. College students shouldn’t pay more than they can afford, he said, especially when the cachet that comes from having attended a more expensive or prestigious school often evaporates 10 minutes into a job interview.

However, Canter said, it’s not unreasonable for a student to graduate with about $20,000 in loans. The way Canter figures it, someone with that much debt must earn about $24,000 per year to afford a monthly student loan payment of about $200.

“That’s about the same as a car payment,” he said. “So you drive an old car for a few years after college.”

That’s reasonable, Canter said.

Staff Writer Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at:

kbouchard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.