Aaron Amirault has good reason to question the property tax assessment on his three-bedroom, 1,900-square-foot home on Middle Road in Falmouth.

Amirault and his wife, Sally, bought the two-story house last January for $235,000 — nearly $90,000 below the town’s $322,800 assessed value. When Amirault challenged the assessment, Town Assessor Anne Gregory dropped it to $286,100, whittling his annual tax bill from $4,173 to $3,695.

But the 39-year-old lawn-care contractor still isn’t happy. The lingering $51,000 difference between what he and his wife paid for their house and what the town says it’s worth troubles him like a stone in his workboot. Falmouth’s assessments meet state standards for being close to market value, but to Amirault, the process seems arbitrary and suspect, and his tax bill remains inherently unfair.

“I’m not against paying my fair share,” Amirault said. “I just want it to be based on the real value of my property.”

He’s not alone.

As the median sale price for homes in Maine continues to fall — from a high of $194,000 in 2007 to $169,000 for the year ending Nov. 30 — many homeowners across the state are asking why their property taxes aren’t falling.

The answer they’re most often hearing isn’t likely to please them: The gap between assessed values set by municipalities and market values established by recent sales is still generally narrow, falling within 10 percent statewide.

More importantly, when municipalites do lower assessments, property owners see little change in their tax bills because towns and cities simply raise the tax rate to cover the cost of running local government. The only real way to reduce municipal budgets or tax bills is to reduce spending on police, schools or other public services.

“If you roll back property values for everybody by 10 percent, it shouldn’t change their tax bills,” said Dave Ledew, director of the state’s Property Tax Division.

“Assessors are expected to assign equitable values to similar properties so each taxpayer pays a fair share of the cost of local government.”

STATE’S TWO TESTS OF FAIRNESS

But whether a property owner is paying his or her fair share can be in the eye of the beholder, leading many Mainers to challenge their property assessments.

Two or three people call or visit Gregory’s office in Falmouth each week, asking her to review or reduce their assessments.

She stands by her property values, based on a 2008 townwide revaluation, and makes minor adjustments when warranted. She’s nice about it, but she tells people, “When the market value was going up and your assessed value was lower, you weren’t in here asking for your assessment to be increased. Well, the reverse is true now.”

Still, the high level of public interest led Gregory, a board member and former president of the Maine Association of Assessing Officers, to give a presentation on the local TV channel on the nuts and bolts of property assessments.

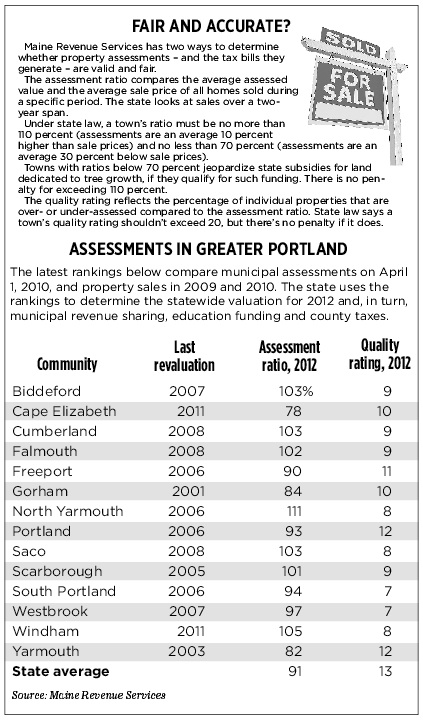

Maine Revenue Services uses two methods to test whether property assessments — and the tax bills they generate — are valid and fair.

The assessment ratio compares the average assessed value with the average sale price of all homes sold during a specific period. Under state law, a town’s assessments should not be more than 10 percent higher or 30 percent lower than average sale prices.

The second method — the quality rating — determines the percentage of individual properties in a town that deviate from the assessment ratio. That number should fall below 20 percent.

Each of Cumberland County’s 14 munipalities passes both tests. (See chart.)

“Our assessments remain equitable,” Gregory said in an office interview. “Just because the real estate market isn’t great right now, it doesn’t mean our assessments aren’t valid.”

In September 2010, 10 homes in Falmouth sold for an average $423,000, with an average assessment of $427,000. That produced an assessment ratio of 101 percent, meaning that assessments were, on average, 1 percent above selling price.

A year later, 12 homes sold in September for an average $461,000, with an average assessment of $455,000. That produced an assessment ratio of 99 percent, meaning assessments were, on average, 1 percent below selling price.

PROCESS PRIMARILY SUBJECTIVE

Gregory and other assessors say they strive to make sure assessments are accurate and equitable so municipal taxes are divided fairly among property owners.

In truth, assessing remains a largely subjective process despite advances in technology, including geographic information systems and real estate appraisal software. Better building materials may have no impact on assessments. A slight waterfront view can boost a home’s value beyond reason.

Maine Revenue Services provides minimal oversight given state laws that set market-related assessment standards but impose few or no penalities. As a result, some municipalities view the standards as guidelines rather than requirements.

While the state’s Property Tax Division encourages munipalities to do regular townwide revaluations to keep assessments current, the process can cost more than $300,000 and take one to two years to complete.

As a result, many towns now make incremental adjustments or do in-house revaluations. Special software allows assessors to keep track of sales and building permits, make changes to individual property assessments and adjust values on similar properties accordingly.

That’s the strategy Rick Mace takes as town assessor in York, which has an assessment ratio of 100 percent and a quality rating of 8. The average selling price for a house in York this year was $445,611, and the average assessed value was $436,648.

It takes about two months for Mace and his staff to update assessments on about 10,600 properties each year. This year, 900 properties increased in value, 4,217 stayed the same and 5,485 fell in value. Some assessments dropped as little as $100; a few increased $100,000 or more.

“Every year, there’s a handful of the same people who come in and question their assessments,” Mace said. “It’s like a game for some of them. I take the time to meet with each of them, because sometimes assessors make mistakes.”

These days, Mace sees more people seeking assessment increases because they want the town’s value to match a higher selling price. It rarely works in their favor. One property owner asked him to increase a $500,000 assessment on a house that was listed on the market for $750,000.

“When I went out to look at the property, I had to reduce it even more,” Mace said. “He wasn’t too happy with me.”

COMMERCIAL PROPERTY A CHALLENGE

Elizabeth Sawyer, the assessor in South Portland and Westbrook, recently met with a resident of an upscale South Portland neighborhood who wanted her to reduce his $700,000 assessment because a house next door recently sold for $500,000.

“He’s convinced the whole street should be reduced because of that one sale,” Sawyer said. “One of our biggest challenges now is educating people about the market.”

Sawyer said there are sane real estate transactions, when houses sell for pretty much what they’re worth. Then there are foreclosures, shortsales and other transactions where the sellers are forced or willing to let properties go for a lot less than they’re really worth.

To keep up with market forces, Sawyer made across-the-board reductions in 2009, by 5 percent in South Portland and by 10 percent in Westbrook; she followed with a 10 percent reduction in South Portland’s land values in 2010.

As a result, South Portland and Westbrook have assessment ratios of 94 percent and 97 percent, respectively, and quality ratings of 7.

Sawyer’s greater challenge has been managing commercial property assessments in a down market.

When the owners of the Maine Mall in South Portland sought an abatement, she reduced their assessment from $268.6 million in 2006 to $252.9 million in 2009 to $219.8 million in 2010. Still, the mall’s owners have appealed the $48.8 million reduction, though it saves them $785,680 on their annual tax bill.

Sawyer also reduced the assessment of the South Portland printing plant of MaineToday Media, which publishes The Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, the Kennebec Journal in Augusta and the Morning Sentinel in Waterville. The real estate assessment dropped from $16.9 million in 2008 to $12 million today, saving the company $78,890 on its annual tax bill.

When commercial assessments drop, other commercial and residential property owners have to pick up the slack, because the cost of running city government is redistributed, Sawyer said.

In Falmouth, Assessor Anne Gregory recently visited Aaron Amirault’s property on Middle Road and reduced his assessment to reflect the lack of a finished basement and a smaller backyard deck.

Comparing the house to other similar properties in town, she figures Amirault got a deal on his 1993 Colonial with a detached garage. She likens it to getting a bargain an anything, from a designer dress to a late-model car. Just because you paid less than the going rate, she says, doesn’t mean it’s worth less.

“We’re trying to predict the value of 4,000 homes in Falmouth,” Gregory said emphatically. “If we get within 10 percent, that’s a bull’s-eye.”

Staff Writer Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at:

kbouchard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.