AUBURN – Surrounded by towering piles of electronic equipment, a half-dozen workers at eWaste Recycling Solutions spend their days prying apart old TV sets and computer monitors.

It takes about three minutes to separate glass, plastic, metals and cathode ray tubes, which may contain lead and other toxic substances. Later, the manufacturers of the products will receive a bill for the work, which, in the case of Sony Electronics Inc., is 36 cents a pound.

“Before, the cost was borne by municipalities, or the consumer paid a tipping fee at the recycling center,” said Rick Dumas, chief executive officer of eWaste, which employs 15 to 25 workers a year.

Dumas and his employees are among the beneficiaries of Maine’s seven-year-old electronic waste law, which was designed to prevent electronic equipment from filling up landfills and releasing toxic substances into the environment.

The law is also one of the environmental measures that may be subject to a repeal effort by Gov. Paul LePage, who is looking to slash environmental regulations that, in his view, get in the way of a friendly business climate, job creation and an improved economy.

In his six-page, 63-point list of ideas for regulatory reforms, LePage proposed reviewing “all consumer products recycling and ‘take-back’ statutes and revise as necessary to develop a policy that ensures that manufacturers do not have to pay to recycle their consumer products and that these standards do not exceed those set in federal law.”

LePage was referring to the state’s so-called product stewardship statute, including the electronic waste law, which requires manufacturers of certain products to pick up the costs of recycling them.

Maine was the second state in the nation, following California, to adopt an electronic waste law in 2004. Today, there are 24 states with similar laws, but no federal law exists.

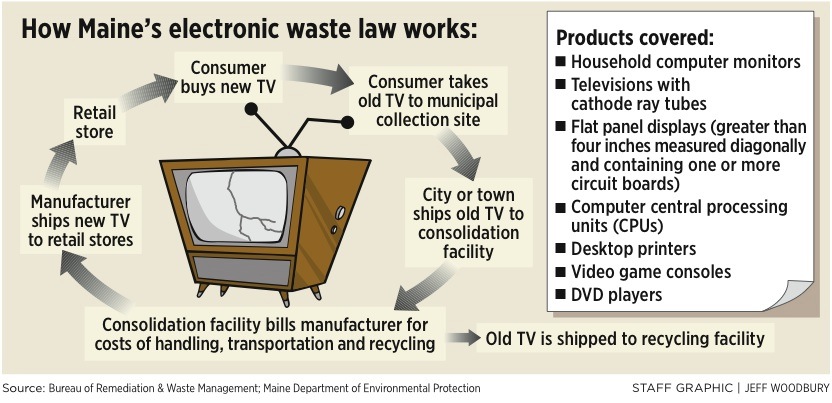

In Maine, manufacturers must pay for the cost of recycling television sets, computer monitors, desktop printers, laptop computers, portable DVD players, game consoles and digital picture frames, which are more costly to recycle than other electronics.

Each manufacturer is responsible for paying companies like eWaste Recycling Solutions for the costs of disposing of their share of the electronics. Manufacturers must pay a $3,000 annual registration fee, and those that don’t participate may not sell their products in Maine. The fees that eWaste Recycling charges manufacturers are approved by the state Department of Environmental Protection.

Cities and towns are required to collect the equipment. Some communities do so at transfer stations, while others organize collection days, sometimes in concert with other communities.

Just how abolishing the electronic waste law would improve the state’s economy or create jobs is unclear.

The electronic waste law spawned at least one company, eWaste in Auburn. It, along with Universal Recycling Technologies in Dover, N.H., which also employs Mainers, handles more than 90 percent of the state’s electronic waste, said Dumas, the eWaste CEO.

No specific answers are yet available from the LePage administration. Dan Demerritt, LePage’s spokesman, said the proposals are in their early stages and details are still forthcoming.

But, Demerritt said, it is the administration’s view that the electronic waste and other product stewardship laws are bad for business and consumers.

The fees charged to manufacturers, for example, are typically passed on to customers in the form of higher prices.

“Maine’s specific take-back rules force manufacturers and retailers who want to operate here to create costly recycling systems that do not exist in other states. For consumers, it means higher prices and fewer choices,” Demerritt said.

The Maine Chamber of Commerce has not taken a position on the electronic waste law. The chamber supported the adoption of the state’s product stewardship law last year, making Maine the first state in the country to set up an ongoing process for the Legislature to add new products to the list.

The list presently includes cell phones, mercury batteries, auto switches and thermostats, and compact fluorescent bulbs.

The Consumer Electronics Association, the Arlington, Va., trade organization for the consumer electronics industry, would welcome changes to Maine’s electronic waste law, said Walter Alcorn, vice president of environmental affairs.

“The Maine program is one of the most expensive state programs in the country, and the $3,000 fee is a long-standing concern because it hits smaller manufacturers the hardest,” said Alcorn.

He said his association is committed to recycling but supports voluntary programs such as Best Buy’s, which takes back electronics at its 1,200 stores.

The Maine Municipal Association, which has embraced most of the LePage deregulation proposals that would affect cities and towns, does not support getting rid of the electronic waste and other product stewardship laws because doing so could raise property taxes.

The electronic waste law has been effective in cutting down on municipal waste. Since 2006, 22 million pounds of electronics were recycled under the program, according to the DEP. That saved municipal taxpayers about $7 million and took 3.3 million pounds of lead and other toxic substances out of the waste stream.

The state’s household electronic recycling rate went from 3.2 pounds per capita in 2006 to 6.19 pounds in 2009, the latest data available.

And there is room to grow because the program is capturing only half of the TV sets and computers being tossed out by households. State Rep. Melissa Walsh-Innes, D-Yarmouth, has filed a bill this session to expand the program to small businesses.

It is true that under the program, Mainers have fewer shopping choices for TV sets. There are 17 manufacturers of TVs and computer monitors on the “do not sell list” distributed to Maine retailers. Those companies elected not to pay the registration fee.

But consumers are saving on disposal costs. Before the law was passed in 2004, municipalities typically charged consumers $25 to dispose of a television set. Now that manufacturers have to pay the recycling costs, handling fees have been reduced to $2 to $4. Some cities and towns, such as Portland, have eliminated fees.

Electronic recycling laws are not under fire in other states, said Jason Linnell, executive director of the National Center for Electronics Recycling.

He said that 65 percent of the country’s population is covered by electronic waste recycling laws.

“No state has rolled back their program. If anything, they are expanding them,” said Linnell.

Staff Writer Beth Quimby can be contacted at 791-6363 or at:

bquimby@pressherald.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.