WASHINGTON – The government’s hunt for Osama bin Laden has left the country questioning whether the tactics used to interrogate suspected terrorists were successful and lawful. With his death, both sides of the debate have regrouped along familiar lines, claiming they were right all along.

But America’s greatest counterterrorism success does not represent a victory for either camp. Rather, it paints a clearer picture of the CIA’s interrogation and detention program, revealing where it was successful and where its successes have been overstated.

At its core, the hunt for bin Laden evolved into a hunt for his couriers, the few men he trusted to pass his personal messages to his field commanders.

After the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, detainees in the CIA’s secret prison network told interrogators about one of al-Qaida’s most important couriers, someone known only as Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti. He was a protege of al-Qaida’s No. 3, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.

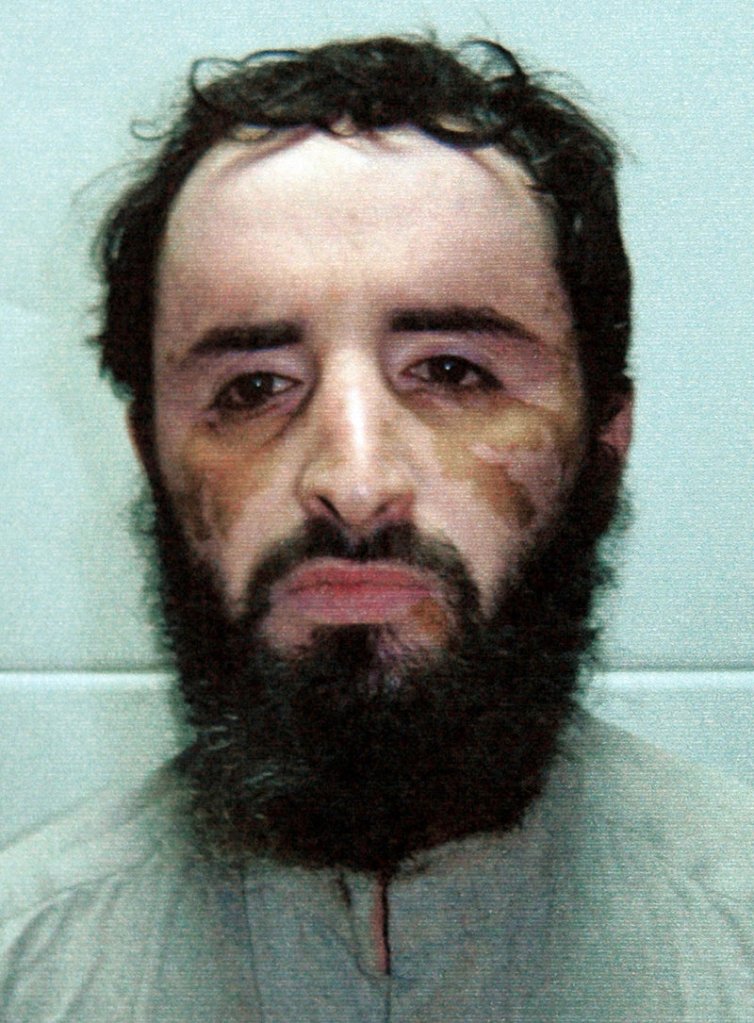

In 2003, the CIA captured Mohammed, the group’s operational leader.

Mohammed was interrogated using what the agency called “enhanced interrogation techniques” such as sleep deprivation and the simulated drowning technique known as waterboarding. Months after being waterboarded, Mohammed acknowledged knowing al-Kuwaiti, former officials say.

“So for those who say that waterboarding doesn’t work, to say that it should be stopped and never used again: We got vital information, which directly led us to bin Laden,” the chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee, Rep. Peter King, R-N.Y., said last week.

But current and former officials directly involved in the interrogation program say that’s not the case.

Mohammed acknowledged knowing al-Kuwaiti after being waterboarded, but he also denied he was an al-Qaida figure or of any importance. It was a lie, much like the stories Mohammed said he made up about where bin Laden was hiding.

Even after the CIA deemed him “compliant,” Mohammed never gave up al-Kuwaiti’s real name or his location, or acknowledged al-Kuwaiti’s importance in the terrorist network.

But the detention program did play a crucial role in the search for bin Laden.

In 2004, top al-Qaida operative Hassan Ghul was captured in Iraq. In a secret CIA prison, Ghul confirmed to the CIA that al-Kuwaiti was an important courier. In particular, Ghul said, the courier was close to Faraj al-Libi, who had replaced Mohammed as al-Qaida’s operational commander.

The CIA had less success when it captured al-Libi.

Al-Libi was not waterboarded. But he did get the full range of enhanced interrogation, including intense sleep deprivation, former officials recalled. Despite those efforts, al-Libi adamantly denied knowing al-Kuwaiti. He acknowledged meeting with an important courier, but he provided a fake name.

Both he and Mohammed withheld or fabricated information, even after the agency’s toughest interrogations.

That gave credence to what many longtime interrogators have maintained, that increasingly harsh questioning produces information but not necessarily reliable information.

Given what they knew from other detainees, CIA interrogators suspected that al-Libi and Mohammed were lying about al-Kuwaiti and that it must be important if they were so committed to withholding this information. So they reasoned that, if they could find al-Kuwaiti, they might find bin Laden.

Years later, thanks to help from other informants and an intercepted phone call involving al-Kuwaiti last year, the CIA was proved right. Kuwaiti unwittingly led the agency to bin Laden’s doorstep in Pakistan.

“They used these enhanced interrogation techniques against some of these detainees,” CIA Director Leon Panetta said this past week. “But I’m also saying that, you know, the debate about whether we would have gotten the same information through other approaches, I think is always going to be an open question.”

The Obama administration has labeled waterboarding torture. While Attorney General Eric Holder has said he will not prosecute any officers who followed the rules laid out by CIA, White House and Justice Department lawyers, he has appointed a prosecutor to review cases in which detainees died.

CIA officers involved in finding bin Laden said they are frustrated that the entire detention and interrogation program and the killing of bin Laden have been reduced to a debate over waterboarding.

“People can debate the value of any single piece of information that may or may not have come from a program like that,” said Rob Dannenberg, the former chief of operations at the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center, who retired in 2007. “But in the aggregate and over the course of time, you are going to unravel the best clandestine organizations in the world with patience and persistence.”

Obama shuttered the CIA’s prison system soon after taking office. Human rights advocates cheered the end of a system in which detainees were held indefinitely, without access to lawyers or the International Committee of the Red Cross, as is normally required.

Critics accused the president of abandoning the strategy that had worked, of capturing terrorists and questioning them. Instead, the U.S. has increased airstrikes from unmanned Predator drones, which have killed terrorists in the tribal regions along the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan.

“We weren’t capturing people anymore, they were just ending up dead in the tribal areas,” said Bob Grenier, who ran the Counterterrorism Center from 2004 to 2006.

When that happens, Grenier said, the CIA doesn’t get to inspect cellphones or documents or whatever else is in the room during the capture.

“They take their secrets with them,” Grenier said.

Obama was unable to fulfill his pledge to close the Guantanamo Bay military prison, where suspected terrorists are held. He had hoped to move many onto U.S. soil for trial, but political opposition stalled that effort. Now, if the CIA captures a major terrorist abroad, it’s unclear what the U.S. would do with him.

Though the CIA prisons are closed, Afghanistan is one possibility. There, the U.S. military maintains a network of secret jails where detainees are being held and interrogated for weeks, including one run by the elite special operations forces at Bagram Air Base in Kabul.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.