WEAVERVILLE, N.C. – Jim Hurst has doted on his trees, arranged in three “families” on a bluff high above the rushing French Broad River.

He installed a drip irrigation system to help rejuvenate this former hayfield’s powdery, depleted soil. To protect against browsing deer, he girded the delicate sprouts in plastic sleeving and wire mesh. In the four years since planting the fuzzy, deep-brown nuts, he nursed the seedlings — through back-to-back droughts, a killing frost, even an infestation of 17-year locusts — applying herbicides and mowing between the rows to knock down anything that might compete.

Then, on a hot day this past June, Hurst moved methodically along the steep hillside, a petri dish in his left hand, and infected the young saplings with the fungus that will almost certainly kill them.

It wasn’t malice, but science — and hope — that led him to take such an action against these special trees.

“My mother’s family never stopped grieving for the (American) chestnuts,” the 51-year-old software engineer and father of two said as a stiff breeze rustled through the 110 or so surviving trees, many already bearing angry, orange-black cankers around the inoculation sites.

“Her generation viewed chestnuts as paradise lost.”

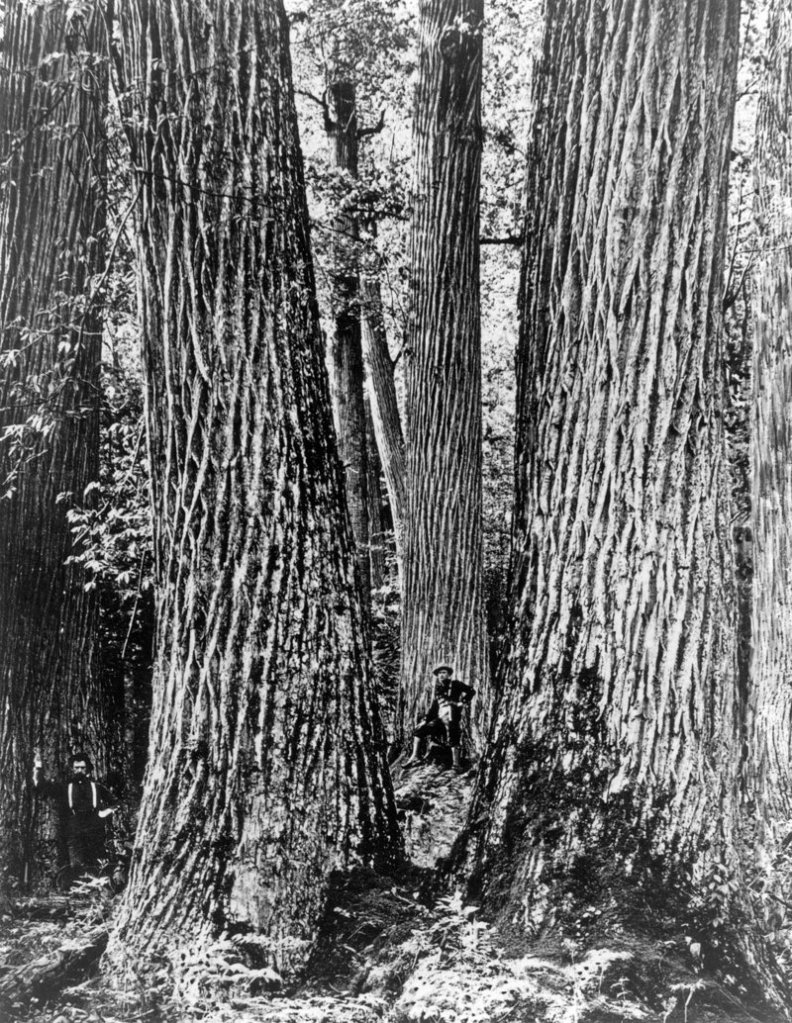

Hurst hopes the trees on his hillside farm — part of a vast experiment in forest plots where this “linchpin” species thrived before the onslaught of an imported parasite — might hold the key to regaining that Eden. The American chestnut once towered over everything else in the forest. It was called the “redwood of the East.” Dominating the landscape from Georgia to Maine, Castanea dentata provided the raw materials that fueled the young nation’s westward expansion, and inspired the words of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Then, the blight struck. By the 1950s, this mightiest of trees was all but extinct — “gone down like a slaughtered army,” in the words of naturalist Donald Culross Peattie.

Now, after 30 years of breeding and crossbreeding, The American Chestnut Foundation believes it has developed a potentially blight-resistant tree, dubbed hopefully, the “Restoration Chestnut 1.0.”

At a national summit in Asheville in mid-October, the group’s board adopted a master plan for planting millions of trees in the 19 states of the chestnut’s original range.

This year, volunteers in state chapters established seed orchards that will soon begin producing regionally adapted nuts for transplanting into the wild. But as those who attended the recent summit heard, much hard work remains — and much uncertainty. The restoration tree is being introduced onto landscape that has long since learned to do without the once-indispensable American chestnut.

Will it crowd out other trees and plants we have come to value in the past century? How do you convince landowners and government agencies that it’s worth the money and effort?

And there are those who will question the wisdom of trying to bring back something that could not survive on its own or, worse yet, “engineering” a replacement that can.

“I think that’s something worth fighting for,” Hurst said. “To fix something that’s broken.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.