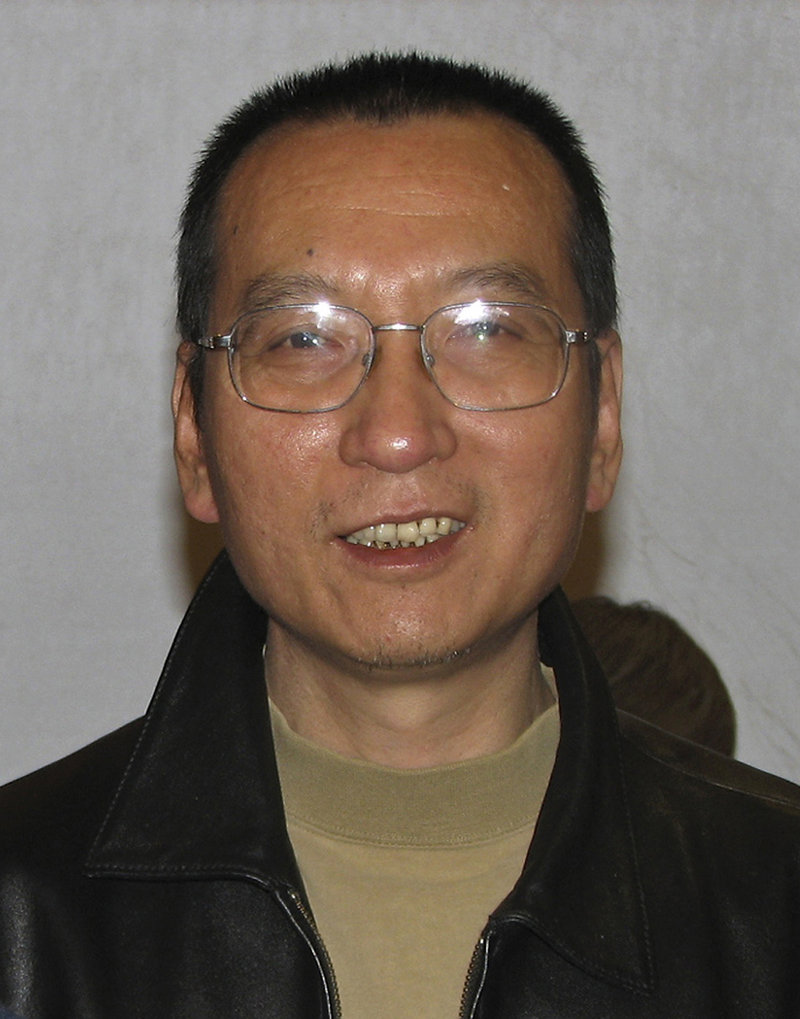

Liu Xiaobo, an irrepressible, chain-smoking Chinese dissident imprisoned last year for subversion, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize on Friday for helping to spearhead a campaign for more freedom in China.

In a statement, the Nobel committee said Liu, 54, deserved the prize “for his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.” Liu joins German pacifist Carl von Ossietzky, who was awarded the prize in 1935 while he was jailed by the Nazis, as the only two to win the prize while in prison.

Analysts said the honor was aimed at pressuring China to ease its crackdown on religious and political activists.

But the government of China denounced the award as “a desecration” and said the honor should have gone to someone focused on promoting international friendship and disarmament.

“Liu Xiaobo is a sentenced criminal who has violated Chinese law,” a spokesman for China’s Foreign Ministry said in a statement. The spokesman, Ma Zhaoxu, said honoring Liu “runs counter to the principles of the Nobel Peace Prize.”

President Obama praised the award, saying the Nobel committee “has chosen someone who has been an eloquent and courageous spokesman for the advance of universal values through peaceful and non-violent means, including his support for democracy, human rights and the rule of law.”

In a statement released by the White House, Obama said that “America will always be a voice for those aspirations that are universal to all human beings.” Although China has made “dramatic progress in economic reform and improving the lives of its people” over the past 30 years, “this award reminds us that political reform has not kept pace, and that the basic human rights of every man, woman and child must be respected,” he said. “We call on the Chinese government to release Mr. Liu as soon as possible.”

After the prize announcement, the Chinese government called in the Norwegian ambassador in Beijing to protest the award, news agencies reported.

The Nobel committee lauded Liu’s efforts over more than two decades to demand freedom of speech, assembly, religion and other forms of expression for Chinese citizens.

China’s “new status” as the world’s second-largest economy “must entail increased responsibility,” the committee said. It said Beijing must heed the call of Liu and others to award its citizens the most basic democratic freedoms.

“Through the severe punishment meted out to him, Liu has become the foremost symbol of this wide-ranging struggle for human rights in China,” the Nobel statement said.

Liu is serving his 11-year sentence at Jinzhou prison in Liaoning, hundreds of miles from his home and wife, Liu Xia, in Beijing.

In an interview shortly before the announcement, Liu Xia said she was thankful that her husband’s physical condition seems to have improved in jail, and grateful that he’s allowed to read and that the two can exchange regular letters.

“We have no regrets,” she said. “All of this has been of our choosing. It will always be so. We’ll bear the consequences together. I’ve known Liu since 1982. I’ve watched him change little by little year by year, and we know that we have to pay the price under the current situation in China.”

In the weeks running up to the announcement, Liu was considered a top contender to win the award. But China’s government had warned Norway not to award Liu its most prestigious prize, saying that the essayist did not qualify for the honor.

Analysts predicted that in the short term, China’s one-party state would react to the award by intensifying an already tough campaign against dissidents, religious activists and non-governmental organizations. Although China outwardly appears strong, with a world-beating economic growth rate, prosecutions for “state security” offenses are approaching numbers not seen since the bloody crackdown on student-led protests around Tiananmen Square in 1989.

But in the long term, a wide spectrum of Chinese and foreigners said, Liu’s award could resonate more deeply within China than any similar act in years — significantly more so than the Nobel Peace Prize that was awarded to the Dalai Lama in 1989 or the Nobel prize for literature given to dissident writer Gao Xingjian in 2000.

First, Liu will be the first Chinese citizen to ever win the award. The Dalai Lama — who after the Nobel announcement called upon China to free Liu — has status as a refugee. And Gao is a French citizen.

Second, Liu, unlike most Chinese dissidents, remains well-known and well-liked in China. Prickly, with a thick northern drawl, tobacco-stained teeth and an infectious laugh, he has always been considered part of the “loyal opposition,” less a theoretician of a democratic revolution than a tough urban gadfly.

Although in and out of jail for two decades for stating his beliefs, writing letters and challenging the state, Liu has escaped the sentence of irrelevance meted out to so many of his dissident contemporaries.

Some observers, however, said the award would feed into a sense among many young Chinese that the West is out to get China and that Cold War thinking still dominates mind-sets in the developed world.

“I worry about the effect of this prize on China’s younger generation,” said Zhu Feng, a professor of international relations at Beijing University. “It will be seen as new evidence about how the West is unfriendly to China.”

Liu’s latest sentence was his longest. Announced on Christmas 2009 — because the Chinese government believes Westerners are less likely to take notice on a holiday — Liu’s sentence of 11 years was for attempting to subvert the state.

His specific crime was that he volunteered to have his name lead a list of signatories to a document called “Charter 08.”

Modeled after the Charter 77 movement in Czechoslovakia during the Cold War, Charter 08 called for greater freedom of expression, human rights and for free elections.

Ultimately, more than 8,000 people have signed China’s charter.

Published on Dec. 10, 2008, the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the charter “was to put a stake in the ground and say here’s an alternate vision of China,” said Perry Link, the renowned China scholar who worked with the group to translate their manifesto into English. “It was definitely a long-term program.”

Among the demands were for a judiciary not controlled by the Communist Party, meaningful elections and the freedoms of association, assembly, expression and religion.

“The current system has become backward to the point that change cannot be avoided,” the charter read. “This situation must change! Political democratic reforms cannot be delayed any longer!”

Liu played an important role as the crafters of the charter hashed out the wording, Link said. He fought to excise any mention of the banned sect Falun Gong from the document because, he argued, the charter’s purpose should not be to deal with specific human rights cases.

And he helped work out a compromise over mentioning the Tiananmen Square crackdown — which was raised in the preamble but not in the body of the charter.

Link, who spent much of that month talking with Liu and others as the manifesto went from one draft to another, recalled that Liu wasn’t a leader of the group in the beginning.

“But once he saw it was going somewhere, he naturally volunteered to be out front,” Link said.

Liu didn’t hog publicity, Link added, “he just doesn’t shrink from putting his head on the line. He was like a moth to the flame.”

After he was sentenced, Liu’s attorney released a simple statement from his client: “I have long been aware that when an independent intellectual stands up to an autocratic state, step one toward freedom is often a step into prison,” it said. “Now I am taking that step; and true freedom is that much nearer.”

Ai Weiwei, a signatory of the Charter 08 document who designed the Bird’s Nest stadium for China’s Summer Olympics, said Friday’s award was at least a sign that “the world is paying attention to China.”

But the award “won’t change much in China,” Ai predicted. “More people need to wake up.”

Liu has taken risks with his life throughout his career. In 1989, he left a cushy post as a visiting scholar at Columbia University to return to China to participate in demonstrations in Tiananmen Square.

On the night of June 3, 1989, he was one of four dissidents who negotiated with the People’s Liberation Army to allow the last several hundred students to peacefully vacate the square. After the crackdown, he spent two years in jail.

Liu was dispatched to a reeducation camp in 1996 for co-writing an open letter that demanded the impeachment of then-President Jiang Zemin.

From then until his arrest in December 2008, two days before the charter was released, Liu lived a life of constant harassment by the security services. He was repeatedly questioned because of his views or his essays, which were passed online by thousands of his readers.

Liu’s wife said the toughest time for her was after he was arrested in 2008 but before he was indicted. He basically disappeared, she said, into the maw of China’s security state.

“For those 6 1 /2 months, I only saw him twice, it was weird for both of us,” Liu Xia recalled. “I was taken to a hotel in a suburb of Beijing, Xiaobo was taken there, too, and he told me he didn’t know where he was.”

But when the indictment came, “I felt very calm,” she said. “I told our lawyer that Xiaobo would probably be sentenced at least 10 years. Then it came out 11, very close to what I expected.”

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.