WASHINGTON — The former high-ranking National Security Agency analyst now sells iPhones. The top intelligence officer at the CIA lives in a motor home outside Yellowstone National Park and spends his days fly-fishing for trout. The FBI translator fled Washington for the West Coast.

This is what life looks like for some after revealing government secrets. Blowing the whistle on wrongdoing, according to those who did it. Jeopardizing national security, according to the government.

Heroes. Scofflaws. They’re all people who had to get on with their lives.

As Edward Snowden eventually will. The former NSA contractor who leaked classified documents on U.S. surveillance programs is now in Russia, with his fate in limbo. The Justice Department announced last week that it won’t seek the death penalty in prosecuting him, but he is still charged with theft and espionage.

Say he makes it out of there. What next, beyond the pending charges? What happens to people who make public things that the government wanted to keep secret?

A look at the lives of a handful of those who did just that shows that they often wind up far from the stable government jobs they held. They can even wind up in the aisles of a craft store.

Peter Van Buren, a veteran foreign service officer who blew the whistle on waste and mismanagement of the Iraq reconstruction program, most recently found himself working at a local arts and crafts store and learned a lot about “glitter and the American art of scrapbooking.”

“What happens when you are thrown out of the government and blacklisted is that you lose your security clearance and it’s very difficult to find a grown-up job in Washington,” said Van Buren, who lives in Falls Church, Va., and wrote the book “We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose the Battle for the Hearts and Minds of the Iraqi People.” “Then, you have to step down a few levels to find a place where they don’t care enough about your background to even look into why you washed up there.”

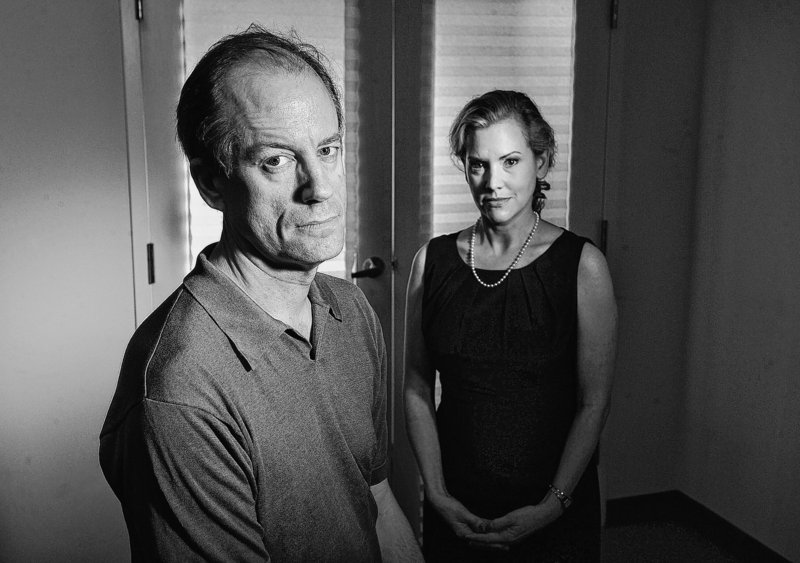

Thomas Drake was prosecuted under the World War I-era Espionage Act for mishandling national defense information.

His alleged crime: voicing concerns to superiors after 9/11 about violations of Americans’ privacy by the nation’s largest intelligence organization (NSA) and later, in frustration, speaking to a reporter about waste and fraud in the NSA intelligence program. (He says he revealed no classified information.)

He lost his $155,000-a-year job and pension, even though in 2011 the criminal case against him fell apart. The former top spokesman for the Justice Department, Matthew Miller, later said the case against Drake may have been an “ill-considered choice for prosecution.”

Drake, now 56, is tall and lanky and dresses as though he’s ready, at any moment, to go on a gentle hike. He is the type of person who likes consistency. He went to work at Apple the day after the charges against him were dropped, surprising his co-workers who thought he would at least take a day off. In 2010, he got an adjunct professor job at Strayer University but was fired soon after, he says, while he was under government investigation.

“I was just blacklisted,” he said, adding that he started his own company but has only had minor work. “People were afraid to deal with a federal government whistleblower.”

Sometimes Washington is just the last place you can stand to be.

Sibel Edmonds was once described by the American Civil Liberties Union as “the most gagged person in the history of the United States.” And she was a regular on Washington’s protest circuit.

She was fired from her work as a translator at the FBI for trying to expose security breaches and cover-ups that she believed presented a danger to U.S. security. Her allegations were supported and confirmed by the Justice Department’s inspector general office and bipartisan congressional investigations, but she was not offered her job back.

She also published a memoir, “Classified Woman — The Sibel Edmonds Story.”

Then last summer, Edmonds, 43, decamped with her 5-year-old daughter and husband to Bend, Ore., which is known as the sunny side of the state. The July weather is 77 degrees without humidity, and there are 33 independently owned coffee shops and nine microbreweries.

“I am touring every single one. Plus, we don’t even have air conditioning here,” she said. “We open the windows and feel the breeze.”

She is still dedicated, she says, to the cause of exposing injustice and making information free. She spends hours running “Boiling Frog Post: Home of the Irate Minority,” a podcast and website that covers whistleblowing and tries to create broader exposure for revelations. She is also founder and director of the National Security Whistleblowers Coalition.

“I think in the current climate, Congress and Washington is a last resort,” she said. “We are going directly to the people and focused on releasing information. And I don’t have to do that from Washington.”

“The connection is really bad, it must be the NSA surveillance program,” Richard Barlow says jokingly when speaking to a reporter on his cellphone from his motor home outside Yellowstone National Park.

“I’m out here with the grizzly bears,” he says. “But this is where I’m comfortable. I’m a 58-year-old seriously damaged, burned-out intelligence officer.”

Barlow says he suffers from chronic PTSD, which makes it hard for him to deal with stress and sometimes other humans. He finds comfort in his three dogs: Sassy, Prairie and Spirit.

His supporters say that shouldn’t be surprising considering what he went through.

Barlow started his career as a rising star tasked with organizing efforts to target Pakistan’s clandestine nuclear-buying networks. He won the CIA’s Exceptional Accomplishment Award in 1988 for work that led to arrests, including that of Pakistani nuclear scientist A.Q. Khan.

He testified before Congress under direct orders from his CIA chain of command, but he says he later became the target of criticism from some of those in the CIA, who were supporting the jihadists (including Osama Bin Laden) in the first Afghan war against the Soviets.

He says he chose to leave the CIA, and in early 1989, he went to work as the first weapons of mass destruction (WMD) intelligence officer in the administration of President George H.W. Bush. Barlow continued to write assessments of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program for then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney. He concluded that Pakistan already possessed nuclear weapons, had modified its F-16s to deliver these weapons, and continued to violate U.S. laws.

The intelligence would have legally precluded a sale of $1.4 billion worth of additional F-16s to Pakistan.

But in August 1989, Barlow learned that the Defense Department had asserted that the F-16s were not capable of delivering Pakistan’s nuclear weapons. Barlow said that Congress was being lied to, and he objected internally.

Days later, he was fired.

“Back then I was disgustingly patriotic and I thought the government is allowing Pakistan to develop and spread nuclear weapons and I got destroyed for trying to stop it,” he said.

He was 35 at the time. His marriage to his 29-year-old wife, who also worked at the CIA, was shattered.

Today, he spends his days, in the wilderness, fly-fishing and bird hunting with his dogs.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.