A group of scientists led by Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences has ventured into the middle of the South Atlantic to study the effects of climate change, ocean acidification and other factors on a type of microscopic plant.

Their research has implications for one of the most important organisms in the oceanic food chain.

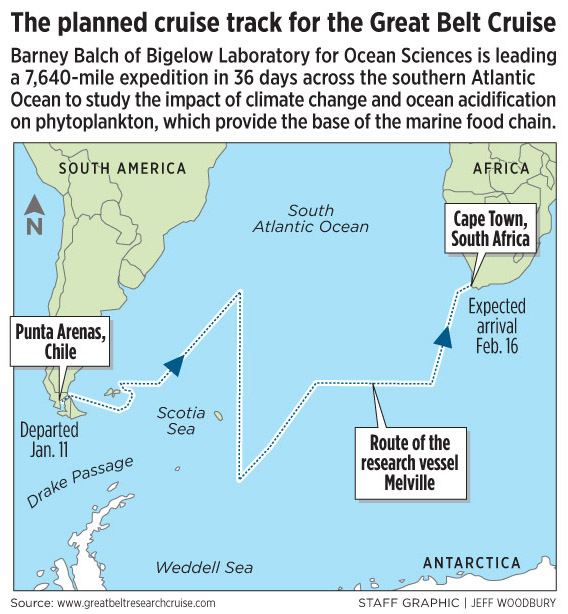

The expedition, led by Barney Balch of the Boothbay Harbor lab, is spending 36 days between the tips of South America and Africa, collecting seawater samples during one of the world’s largest recurring phytoplankton blooms.

“The water is brilliant green, an amazing sight from horizon to horizon,” said Balch, speaking by phone Monday from the research vessel Melville. Six other scientists and staffers from Bigelow and a Colby College chemistry professor are among 23 scientists participating in the 7,650-mile voyage.

Six days into the expedition, Balch said the scientists are already getting results.

Theirs is the first systematic study of the coccolithophore phytoplankton, a microscopic marine plant that covers itself with hard calcium carbonate scales and lives near the ocean surface. Coccolithophores are the base of the marine food chain, and live throughout the world’s oceans. But they are particularly plentiful in the South Atlantic, enough so that their highly reflective scales can be detected by satellites.

The expedition is focusing on about two-thirds of what is known as the Great Southern Coccolithophore Belt, where the plankton blooms in the southern hemisphere’s spring and summer.

The researchers are trying to assess how coccolithophores are affected by increases in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels. The excess carbon dioxide is absorbed by the ocean, forming carbonic acid, which causes the ocean to become more acidic.

Researchers want to know whether the increased acidity is interfering with the chemical process by which coccolithophores form their scales. If the organisms were no longer able to build the shells and their numbers dwindled, it would have huge consequences for the oceans’ ecosystems.

The scientists are working in summertime temperatures of about 50 degrees Fahrenheit, in rolling seas with water temperatures hovering near 40. They are two hours ahead of East Coast time.

So far, the only wildlife spotted have been albatrosses and petrels, which fly in to examine the ship before flying off. The only other human activity seen was the lights of squid boats one night off the Argentine coast.

“Other than that we are all alone,” said Rebecca Fowler, Bigelow’s education director, who is blogging about the expedition.

The research is being financed with a $5.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration is providing satellite imagery. Several public schools in Boothbay Harbor, Mount Vernon, and in Mississippi and Utah, are following the expedition through online activities.

The work entails taking hundreds of very precise water samples. Some of the samples are analyzed on board and others will be examined in land-based labs.

“Some of the analytical instruments we can’t bring out to sea, like a scanning electron microscope. There are some things you can’t do on a rolling ship,” said Balch.

The scientists work in 12-hour shifts around the clock to make the most of their time aboard. They also work at night so they don’t disturb the phytoplankton, which are light sensitive.

Other scientists aboard the R/V Melville are conducting other experiments with the coccolithophores.

Bigelow senior research scientist Ben Twining is analyzing how trace metals, including iron, zinc and cobalt, affect the growth of the coccolithophores. Scientists believe some of these metals, particularly iron, may stimulate scale growth.

Because they are working with metals, they must take extra precautions.

“It is interesting because working on a steel ship we have to go to great lengths to collect water that is not contaminated,” said Twining.

He and his team conduct their experiments in a plastic-encased shipping container to prevent the seawater samples from coming into contact with steel or the boat’s exhaust.

The Bigelow team also includes research associates Bruce Bowler, Dave Drapeau and Sara Rauschenberg and research technician Laura Lubelczyk. Colby’s team includes chemistry professor Whitney King, who is working on chemical analysis, and student intern Annie Warner, who graduated from Colby in December. There are also teams from the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences, and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Fowler has been working with the students who are following the research. She said the expedition is like nothing she has experienced before. She said she is looking forward to the leg of the journey when they near South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

“We could see some whales, porpoises, maybe penguins and icebergs. Everybody is excited,” she said.

Staff Writer Beth Quimby can be contacted at 791-6363 or at: bquimby@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.