The long road back is a place Rachele Burns knows well.

The frustration. The rehab. The fight to stay positive. The quick smile that flashes easily even when her body isn’t cooperating with her dream to play Division I basketball at the University of Maine.

Burns made her UMaine debut this fall, after missing all of her freshman season recovering from a third surgery on the anterior cruciate ligament in her right knee.

But then, after just her fifth game back, Burns went down again, this time tearing the ACL in her left knee.

Personally, the former standout guard at Gorham faces a grueling journey back, both physically and mentally.

Statistically, she stands for an injury that has become an epidemic among female athletes.

Female basketball players seem particularly vulnerable for reasons that are not fully understood in medicine.

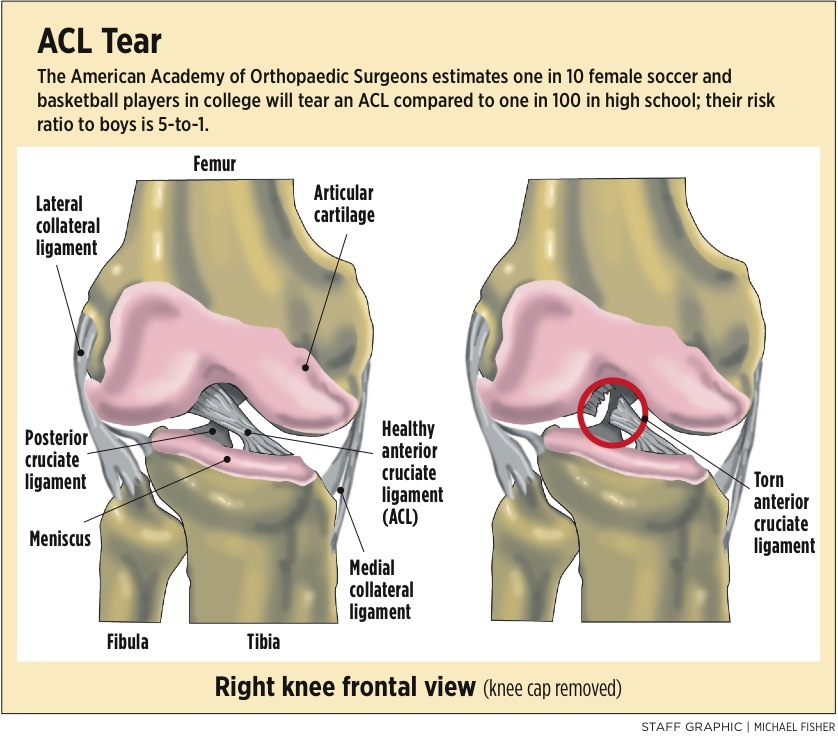

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons estimates one in 10 female soccer and basketball players in college will tear an ACL, compared with one in 100 in high school; their risk ratio to boys is 5-to-1.

“Let’s be real. It does stink. And mentally it will be hard,” said Burns. “But what I’ve learned from all this is you can’t be negative about it. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. I’ll have to focus. I’ll have to work my butt off every single day.

“I’m so close to something I’ve always wanted to do.”

Burns’ resolve has motivated her teammates.

“I’ve been through it, too,” said forward Tanna Ross, who tore her ACL in high school. “So for me it’s easy to see the tremendous heart and love for the game she has. She has no doubt in her mind that she will return.”

STRUCTURAL DIFFERENCES

Burns expects to schedule her ACL surgery with Dr. Thomas Gill, at Massachusetts General, sometime next month. He’s the same doctor who performed the surgery on New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady and wide receiver Wes Welker.

The ACL is a ligament that runs through the middle of the knee, connecting the femur to the tibia. It provides stability and minimizes stress across the joint.

Structural differences exist in the joint between the sexes, said Dr. Thomas F. Murray Jr. of OA Centers for Orthopaedics in Saco.

The size of the femur bone is different, the space where the ACL lives is tighter in a girl than a boy, and the ligament size is smaller in a girl than a boy.

“You can’t change any of those things,” said Murray.

What can be changed is conditioning and the strength of the muscles that surround the joint — both play a part, he said, as does biomechanics.

In basketball in particular, the biomechanics of a player’s vertical leap and agility tend to play a big role in making the ACL vulnerable to tear.

“What happens for girls in general, it’s not how they jump, but how they land,” said Murray. “Their knee tends to turn in or buckle. Boys land with a wider base of support.”

FIVE GAMES, 74 MINUTES

Burns’ tear to her left knee happened Dec. 18 while she was practicing with Maine at its Florida tournament just before Christmas.

She was in the middle of a one-on-one guard drill when her left knee buckled.

“It felt weird. But every time I’ve done it it’s felt different, so I couldn’t tell if I blew my knee out or not,” said Burns.

She stopped practicing, iced it, and went in for an MRI upon the team’s return to Maine. Within two hours she learned she tore the ACL and had a medial meniscus tear.

“My doctor said ‘Rach, I don’t get why this has to keep happening to you. All I’ve seen is you working hard to play the sport you love.’ He just told me, ‘It’s not fair. It’s not fair at all,’” Burns recalled.

Burns first tore her right ACL in high school during basketball season. She returned to play soccer the following fall and tore it again. During her rookie season at Maine she tore the same ligament during the team’s annual preseason blue-white scrimmage and fought back to return this year.

Her college career to date has spanned 74 minutes in five games. She has scored a total of 17 points.

Before college, she was regarded as one of the better female players to rise from a Maine high school, with the movement, court sense and drive to play at the Division I level.

Her decision to battle the new injury came quickly: “I played five games. But I want more. When I first stepped on that court it was the best feeling.”

REPEATED INJURIES RAISE CONCERNS

Burns, like any athlete returning from a major surgery, will have to undergo rigorous rehabilitation that will span some six months.

Re-injury after ACL surgery can be a major concern.

“I don’t know this player’s specific circumstance, but it’s not uncommon to hear about multiple ACL tears in female basketball players,” said Murray. “It happens. And again, that athlete excluded, if we’re talking about once, twice, it’s a concern. A third time you start to wonder what are we not doing? Is it somewhat Darwinian?”

That’s a concern for Burns, though she has no plans to consider ending her career. “What I’m focused on right now is the present, not the future,” she said. “I’m guessing along the road, someday, I’m going to have to get a knee replacement on my right side. When I’m older, who knows?”

Maine Coach Cindy Blodgett said watching Burns struggle has been difficult but inspiring for everyone closely involved.

“She has great fight in her. A resolve in trying to overcome. And that is a great quality that will serve her very well post-college,” said Blodgett. “For her, part of it is survival. I think she’s wise in her approach to be positive and decide to fight back. What’s your other option? To go into a bubble? You can get depressed. You’re going to face those challenges regardless. So you might as well be ready. She has done a phenomenal job dealing with this.”

Blodgett wouldn’t, however, offer a long-term prognosis: “The first step is to get the surgery. The second big step is doing the rehab. People who never had this injury or never played Division I athletics probably don’t have a good grip (of how hard that is). It’s coming back from four ACL tears to play Division I athletics. This isn’t rec league. This is rigorous, 12 months out of the year. It’s admirable to fight back, but we also have to make sure she can walk when she’s 40. That’s my job. My job is to look out for her.”

THE PLAN IS SIMPLE

Rehab programs often center around strength training and conditioning that result in improved agility and vertical leap.

Orthopaedic Associates runs a training center in Saco designed to strengthen the joint for athletes looking to return from surgery or prevent the injury.

In general, said Murray, athletes can focus on preseason conditioning for muscles, endurance and agility drills.

Returning to the court or field comes with risk.

“There is always concern for repeat injury. I’m sure her doctors will talk to her about the risks associated, should you keep going back,” said Murray. “That conversation will happen. But every patient has their own set of values.”

For Burns, the plan is simple: She can’t imagine anything but returning to the court, to the familiar feel of a basketball in her hands, a court alive with the game she loves.

“I have to believe everything happens for a reason,” said Burns. “I didn’t want to believe I’d have to go through another six months of this. But you take what life gives you. You give it 110 percent. And you realize how precious life is.”

Staff Writer Jenn Menendez can be contacted at 791-6426 or at:

jmenendez@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.