AUGUSTA – It’s one sentence at the end of a brief letter that infuses history with a remarkable sense of fate.

It’s also one of more than 300,000 Civil War-related items in the Maine State Archives — and thousands more held by museums and historical societies across the state — that are being dusted off and reviewed on the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Fort Sumter, the April 12-13 fight near Charleston, S.C., that triggered the bloodiest period in U.S. history.

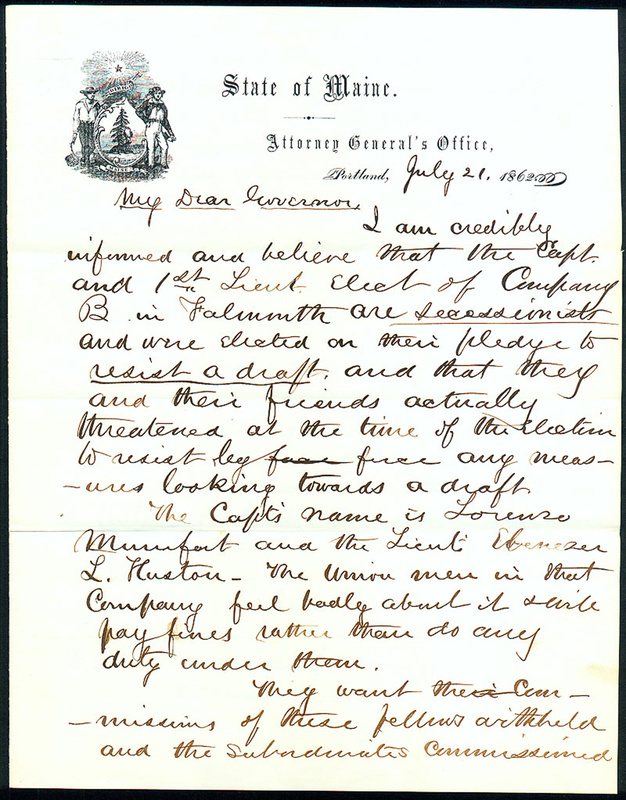

The letter in question was written in July of 1862, more than a year into the war. Maine’s attorney general, Josiah Drummond, sent the note from Portland to inform Gov. Israel Washburn that a pair of Falmouth militia officers were secessionists who planned to resist a draft into the war.

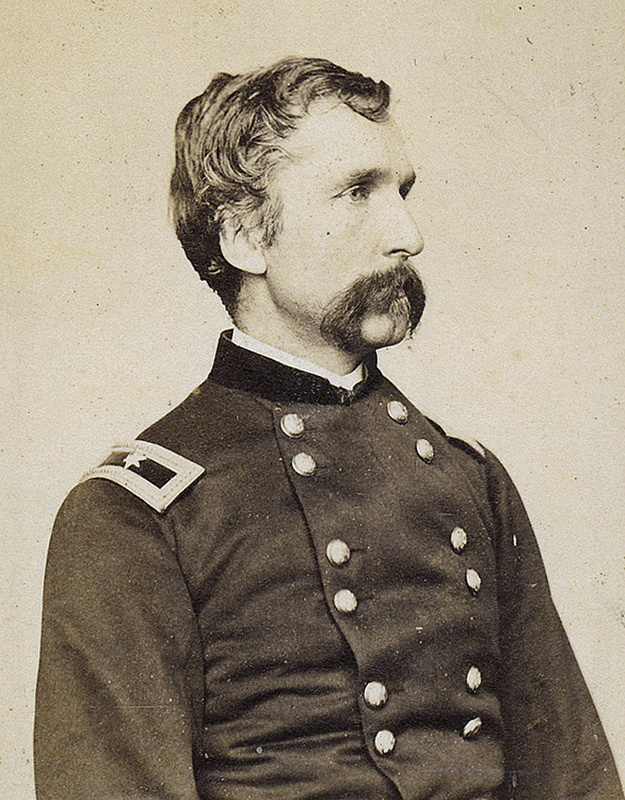

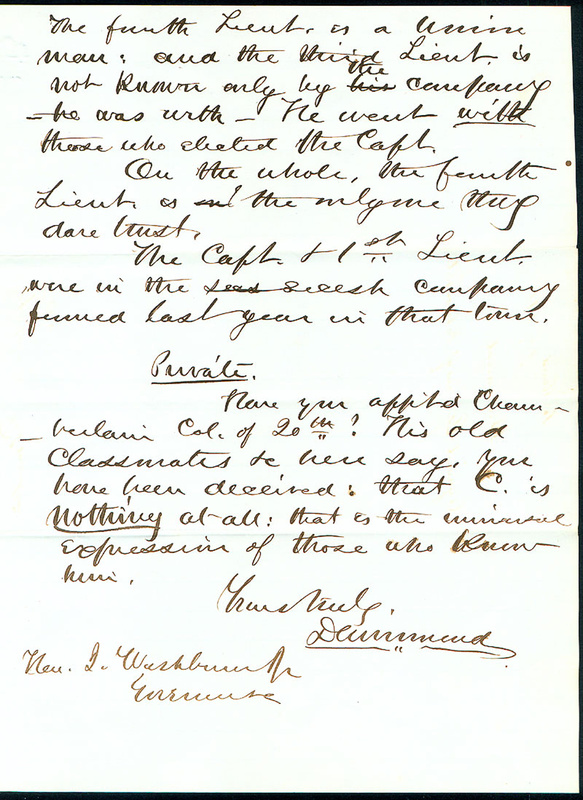

Drummond ended his letter with a scathing, by-the-way postscript on Washburn’s plan to appoint Joshua Chamberlain, a Bowdoin College alumnus and professor, to an officer’s post in the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

“His old classmates etc. here say you have been deceived: that C. is nothing at all: that is the universal expression of those who know him.”

Drummond underlined “nothing” for emphasis.

Washburn ignored Drummond’s warning and appointed the reluctant Chamberlain lieutenant colonel of the regiment, which went on to distinguish itself a year later in the defense of Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Chamberlain rose to the rank of brevetted major general and was shot several times during the war, sustaining injuries that plagued him until his death in 1914 at age 85. On April 12, 1865, Chamberlain, flanked by his men, presided over the formal surrender of arms by Confederate troops at Appomattox, Va.

After the war, he received the Medal of Honor, was elected governor four times, served as Bowdoin’s president for more than a decade and remains one of Maine’s favorite sons.

But what if Washburn had heeded Drummond’s warning? What if Chamberlain had declined the appointment?

“Who knew what was going to become of these people?” said David Cheever, state archivist. “They were absolutely blind to the circumstances they were about to undertake. These were ordinary people in extraordinary times.”

Nearly every Maine family at the time was touched by the war. About 70,000 Maine men were drafted or volunteered — more than 10 percent of the overall population and about 60 percent of eligible men ages 18 to 45, Cheever said.

On Friday, the Maine State Archives will launch a four-year commemoration of the state’s role in the Civil War with a special presentation, “Saving the Union: The Call for Volunteers,” at the Augusta Civic Center. The 1 p.m. event will include historical readings by state officials, musical performances and re-enactment groups recalling Maine’s entry into the war.

In addition, 27 museums and historical societies across the state are collaborating to create the Maine Civil War Trail and mount coordinated war-related exhibits in 2013, marking the 150th anniversary of Gettysburg.

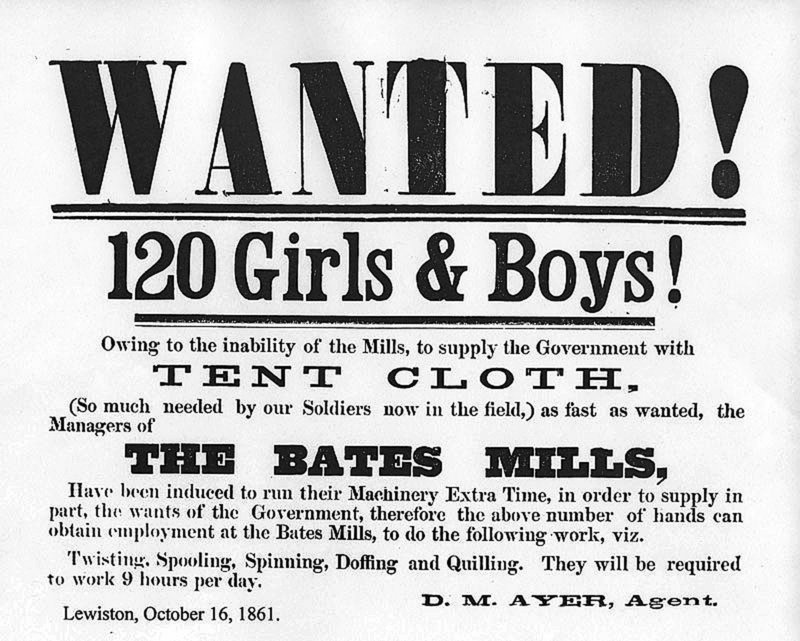

The exhibits will stretch from the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath to the Bangor Historical Society. They will tell the story of draft riots in Kingfield and children in Lewiston mills making cloth for soldiers’ tents.

The trail is being organized by Kim MacIsaac, director of the Fifth Maine Regiment Museum on Peaks Island, which is holding an open house from 1 to 4 p.m. today.

“Maine’s role in the Civil War is largely unknown today,” MacIsaac said. “Everyone knows about Joshua Chamberlain, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg.”

Despite its relatively small population — just 628,279 residents in 1860 — Maine was a fast-growing and influential state because of its manufacturing, shipping, forestry and fishing industries, MacIsaac said.

“And we have plenty of documents and artifacts across the state illustrating Maine’s role in the war,” MacIsaac said.

It’s not surprising that Maine is such a rich repository of Civil War memorabilia. Mainers tend to save things. Old jars for canning vegetables. Scrap wood to build hunting camps. Grocery bags for all sorts of uses.

Maine’s Civil War collections are, however, uniquely comprehensive, organized and well documented, according to Cheever, the state archivist.

The state archives alone contain 14,640 pages of company muster rolls, 180,000 war-related letters, several hundred lithographs, nearly 500 war-related books and journals, the adjutant general’s annual reports, 55,000 service cards, 38,000 veterans’ grave cards, 500 pieces of war-related legislation and five volumes of State House telegram logs. Many of the items are posted online at www.maine.gov/sos/arc or may be viewed at the archives.

The simplest documents tell extraordinary stories.

In a telegram sent in May 1861, the state’s newly appointed surgeon general, Dr. Alonzo Garcelon of Lewiston, notified Gov. Washburn of an outbreak of measles in the Fourth Maine Infantry Regiment that was mustering at Rockland. Garcelon, who would become governor in 1879, asked if he could quarantine the sick soldiers and inoculate the rest.

“Washburn authorized what was then a novel medical procedure,” Cheever said.

Legislative records show that 60 percent of the state’s annual budgets during the war were spent on the war effort, Cheever said. At one point, while legislators argued over funding the purchase of blankets for Maine soldiers, the state took its first casualty of the war. A soldier died of pneumonia while mustered outside the State House in the freezing cold.

The archives also contain more than 3,100 cartes de visite, or calling cards, that feature photos of Maine soldiers. The Union Army didn’t issue dog tags, so many soldiers carried the popular 2-by-4-inch cards so they could be identified if they were killed in battle.

Unfortunately, unsanitary camp conditions proved more dangerous than bullets and caused many soldiers to contract every imaginable disease. Of an estimated 620,000 men who died in the war, Union and Confederate soldiers combined, 414,000 or two-thirds died from disease. Among Maine’s casualties, 3,184 men were killed in battle and 5,257 died from disease.

Chamberlain, Maine’s most famous Civil War soldier, contracted malaria following his success at Gettysburg and was relieved of duty in late 1863 until he recovered. He returned in early 1864 to command the 20th Maine in the 10-month Siege of Petersburg.

In June, Chamberlain was shot through the hip and groin, a near-mortal wound that forced him to wear an early catheter and undergo several futile operations throughout his life to relieve relentless pain and infections.

Regardless of his injuries, Chamberlain was back on the battlefield by November 1864.

“There was always the possibility that your mortal demise was at hand,” Cheever said. “Many more died from disease than were killed in battle, and those who didn’t die often wished they had.”

Staff Writer Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at:

kbouchard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.