As chair of School Administrative District 60 (although expressing my personal opinion), I was troubled by the misleading and erroneous statements in the Washington Post article you published on the results of the recent Program for International Student Assessment tests (“U.S. students losing ground to Asian, European counterparts,” Dec. 3).

We must stop using these tests as some sort of measure of national strength. The idea that the U.S. score on a test of 15-year-olds is a judgment on the world’s most powerful nation is absurd.

The U.S. has always performed at or near the average, and yet we’ve had the world’s largest economy since the 1920s. The list of our national achievements, such as six manned round trips to the moon, only demonstrates the uselessness of tying these tests to national economic performance.

Comparing gross averages among groups is always difficult, and really can’t be done unless the differences between the groups are controlled for. Here, the key differences are the populations of students, national culture and poverty.

• For example, Tom Loveless of the Brookings Institute notes that China has a special deal allowing Shanghai – a city of elites – to be treated as an independent country.

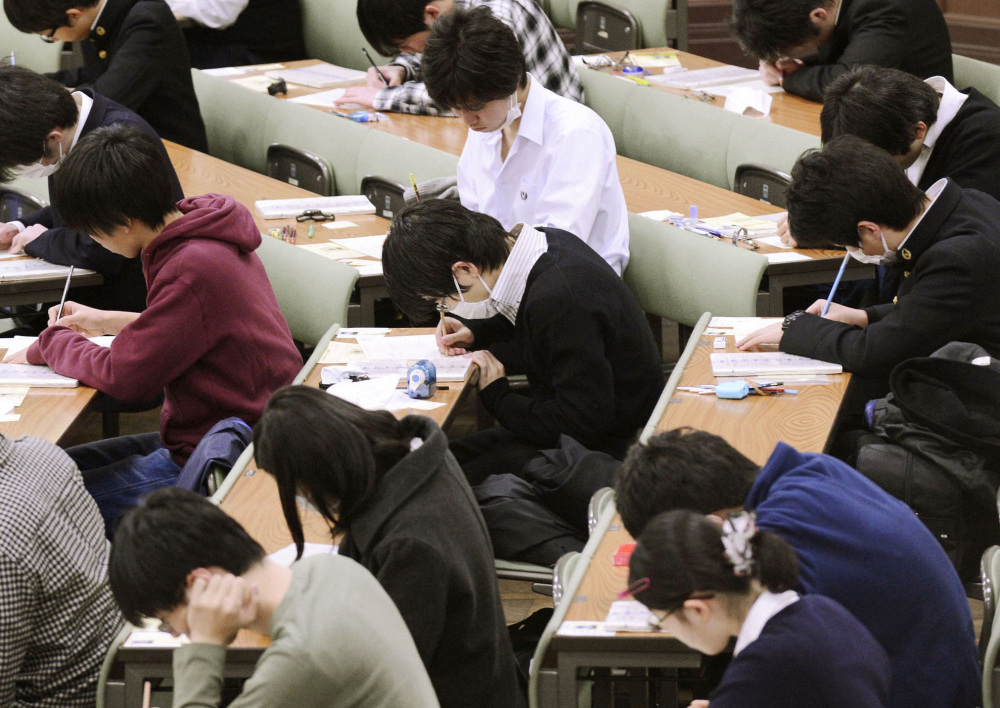

• And as another Post article (“Asians lead the globe on exams, but paying a price”) in the Dec. 5 edition describes, the top-performing Asian countries have national policies that make PISA scores a priority.

• Finally, when one compares schools in other countries with U.S. schools having fewer than 10 percent of students receiving free- and reduced-price lunch, the U.S. students score first in reading and science, and fifth in math.

Clearly the past two decades of school reform (No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top) have failed. Maybe it’s time to stop listening to reformers and their silly comparisons, and get back to educating our children.

David Lentini

North Berwick

Dana Goldstein’s commentary about the Common Core (“The real problem with Common Core,” Dec. 1) raises some excellent questions about the standards’ ability to effectively represent all students’ best interests.

We all agree that our curriculum can be more rigorous, but the question we should be asking is, “Is implementing testing the best way to improve students’ educational experience?”

As a fifth-grade teacher of 26 years, I have seen the amount of time that we have for direct instruction and for student learning experiences be eroded by the addition of curriculum and more standardized testing. Several weeks of school each year are now consumed by various tests and by the preparation and practice for those tests.

Testing success has never been proven to ensure success in college or success in a future career. It is a somewhat narrow skill. More time spent learning new concepts and skills and practicing those skills as a part of a relevant and engaging learning experience would translate to better-prepared citizens.

Testing is not the only way to ensure more rigorous instruction and standards. Other approaches include:

• Improving teacher education.

• Raising the standards to enter the teaching profession.

• Increasing the involvement of educators who actually work with children in the educational planning for our schools.

• Focusing on the inequality of education in the schools of Maine.

• Improving the professional standing of educators in our society.

• Focusing on research that demonstrates what types of learning experiences are most developmentally appropriate for different age groups.

Testing is a glib response at best. Our students are the guinea pigs for these tests. Educators’ concerns are ignored. Testing corporations continue to rake in huge profits. After all these years of MEAs, NWEAs, NECAPS and now the Common Core, does anyone feel like student learning has improved?

Valerie Razsa

Gray

Mobile crisis unit sounds great, but we need details

In her recent Maine Voices column (“An emergency room isn’t always the best place for an emotional crisis,” Dec. 5), Tasha Saunders recommends calling a mobile crisis unit instead of heading to the emergency room in the event of a mental health crisis.

These units, she says, travel around to perform assessments and can often help those they serve avoid going through the ER and incurring long waits and high costs. This sounds like an excellent resource.

She asks why people are not using them. The answer may be that many – like myself – have never heard of mobile crisis units, and therefore would not know how or where to contact one.

Unfortunately, she did not supply this information. Is there a way to get it?

Karen Lewis Foley

Topsham

Charities should rethink using ‘adopt’ in appeals

Most of us would agree that contributing to those in need is an important part of the holiday season. And just after Halloween, a multitude of organizations appeal to our sense of kindness and generosity by launching “Adopt a” campaigns – for instance, we may “Adopt a Turkey,” “Adopt a Veteran” or “Adopt a Child for Christmas.”

As an adoptive parent, I believe using adoption language in this way is disrespectful, and I urge these organizations to use a different term when asking for charitable donations or asking for charitable time.

I assume that these organizations are unaware of the impact of their language, and truly mean well as they create their campaigns. I understand that the needs are great and the language must garner attention, and “adopt” is an emotionally loaded word.

It appeals to our sense of compassion on a visceral level. It infuses our donations with a greater meaning. Dropping money in a bucket seems flimsy compared with adopting a cause.

But please consider how “Adopt a” campaigns can be hurtful, especially to an adopted child. These temporary “adoptions” promote the stigma that adoptive families are not “real” families.

Using the word “adoption” in this way conjures the stereotype of a poor, lonely, lost soul who needs saving, associating adoption with pity. It also promotes the idea that adoption is about money. These stigmas and stereotypes are not reality for adoptive families, and adopted children often feel confusion and shame in response to society’s portrayal.

I applaud people’s kindness and generosity and in no way wish to discourage it, nor do I wish to make anyone feel badly for supporting these charity drives. But it would truly be a gift if organizations would choose to use the word “sponsor” in place of “adopt” when asking for charitable donations or time.

Donna LaNigra

Gorham

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.