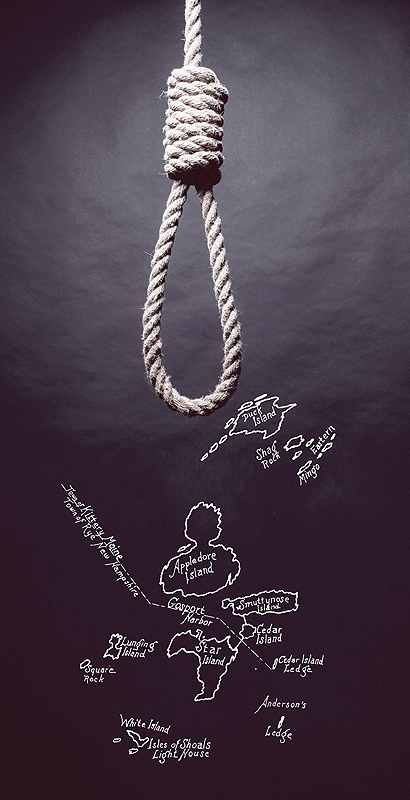

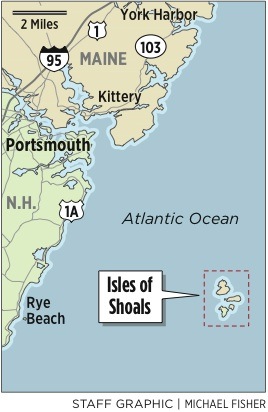

One of Maine’s most bizarre murder cases took place 140 years ago, March 5, 1873, on Smuttynose Island, one of the Isles of Shoals located off Portsmouth, N.H., but within the limits of the state of Maine.

The outcome would fuel the long-simmering controversy over the death penalty, ultimately killing Maine’s 1837 capital punishment law.

Smuttynose was home to a Norwegian fisherman named John Hontvet, his wife, Maren, her sister Karen, their brother Ivan Christenson, and his wife, Anethe. When John and Ivan left Smuttynose on the morning of March 5 to row to Portsmouth for bait, little did they know they would return to the scene of one of Maine’s worst crimes of the century.

As John and Ivan came ashore for bait, they were met by Louis Wagner, a Prussian fisherman who was previously in Hontvet’s employ, and who had lived with the family for just under a year. When the expected bait did not arrive by train, Hontvet remarked to his brother-in-law that they would not be able to return home that night. The Norwegian also made the mistake of mentioning how much he had just cleared in his fishing business.

The two remarks served as a green light to Wagner. On that moonlit March night and with a favorable tide, the 29-year-old Wagner stole a dory and set out for Smuttynose around 8 p.m.

About midnight, a figure slipped into the island’s lone cottage and quietly fastened the door of the bedroom occupied by Maren and Anethe. The midnight marauder ransacked the house for his expected bounty — some $600, according to John Hontvet. He instead found Karen Christenson asleep on a lounge in the kitchen — who made the mistake of waking up.

The intruder seized a chair and began striking her repeatedly until she fell against the bedroom door. The clock fell from the mantel and froze 1 a.m. as the hour of the murder.

Karen’s fall against the door unfastened the latch, and Maren threw it open to discover the murderer poised with a chair in the air, set to strike again. Frantically pulling Karen inside, Maren barracaded the door and directed Anethe to jump out the window and scream in the hopes of alerting neighboring islanders.

Anethe never made it. The intruder bludgeoned her as she screamed in recognition, “Louis, Louis!” Maren Hontvet ran from the house in her nightdress and hid in a rocky cave near the shore for the rest of the night.

In the morning she crept back to the cottage, where she found the bodies of her sister and sister-in-law. The little dwelling had been rummaged, but the killer failed to find Hontvet’s currency hidden in a trunk. His paltry bounty consisted of three $5 bills, some silver change and a few coppers bearing Norwegian stamps.

After finding the money, Louis Wagner fixed himself a snack in the kitchen before rowing back to Portsmouth.

He turned up at his boarding house where he explained his rough appearance — and absence — as the result of too much ale followed by a drunken stupor. Later that day Wagner hopped a train to Boston about the same time Hontvet and his brother-in-law returned to Smuttynose and made their chilling discovery.

By the end of the day police had located Louis Wagner and placed him under arrest. He was returned to Portsmouth, where a mob surrounded him with lynching on its mind.

Wagner was taken to the York County Jail in Alfred to await trial for murder. On June 18, 1873, he was convicted of murder and was returned to the jail — briefly. He staged a sensational escape before finally being captured in New Hampshire.

In September of that year, Wagner was sentenced to be hanged after one year’s confinement at the Maine State Prison in Thomaston.

Why one year? The sentence was consistent with Maine’s 1837 capital punishment law, which stated a sentence could not be executed until the convicted had been confined to the state prison for one year and one day. Wagner would be one of the last to benefit from this law.

The 1837 Maine law also had another stipulation: The sentence could not be completed until the governor issued a warrant ordering the execution, which had no time limit prescribed.

This clause, coupled with Maine’s strong sentiment against the death penalty, meant no murderer had been led to the gallows for 30 years.

Gov. Joshua Chamberlain recommended to the Legislature in 1867 to abolish the 1837 law or require the governor to issue a warrant for execution in a fixed time. No action was taken on either recommendation.

With the Legislature continuing to leave the death penalty squarely in the hands of its governors through the mid-1870s, the executive branch was entering its own protest: They didn’t want to be, for all intents and purposes, the hangmen.

Finally, in 1875, the Maine Legislature responded by requiring the governor to sign a warrant for execution within 15 months of sentencing.

It was this amendment that was ultimately responsible for slipping the noose around Wagner’s neck. But Wagner didn’t go quietly. He surprised his executioners by maintaining his innocence, and the following year, 1876, the death penalty was abolished.

But not for long. Resurrected in 1883, the law managed to pay one last hangman’s salary.

David Wilkenson of Bath was hanged in 1885 for the murder of a Bath policeman, William Lawrence, who happened upon Wilkenson robbing a store. When the officer closed in, Wilkenson fired and killed the policeman.

The case was speedily wrapped up and Wilkenson was arrested, tried, convicted and executed. He would be the last to die at the hands of the state.

On March 16, 1887, state Rep. William Engel of Bangor introduced a bill for the repeal of the death penalty one year later with these words: “Repeal the obnoxious law, and rise one step in civilization.” Religious and activist groups throughout the state applauded the death of the death penalty.

In a final twist to the saga, the murder trial of Louis Wagner, an immigrant from Prussia, marked the first time in Maine history that an immigrant was tried for the death of another immigrant, Maren Hontvet of Norway. Anethe Christenson’s murder did not go to trial.

Karen Marks Lemke of Lisbon Falls is an education professor at Saint Joseph’s College in Standish.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.