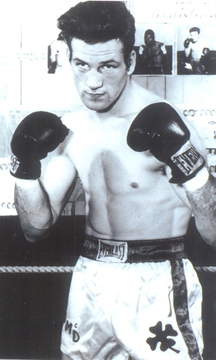

By day he was Officer Jim McDermott, keeping the peace in his adopted city of Holyoke, Mass. By night he was Irish Jimmy McDermott, the fighter who returned to Portland once or twice a month to step between the ropes of the boxing ring at the Portland Expo.

He had earned the cheers that echoed off the old arena’s walls by winning and remembering his roots. To the thousands of fight fans who paid $3 or $1.50 for a ticket to the Thursday night fights some 45 years ago, McDermott was the kid off the Scarborough farm who had made something of himself as a man.

“It’s true,” said McDermott. “I’d be nothing without boxing.”

Saturday night, Bob Russo of the Portland Boxing Club will pay tribute to McDermott and dozens of other men who made Portland one of the busiest fight towns on the East Coast. Russo will do so by promoting the first fight card of young pro prospects and amateurs at the Portland Expo in 20 years.

Ryan Kielczewski of Quincy, Mass., is 24 years old, unbeaten in 17 super featherweight fights and in the main event. Current and former Portland Boxing Club members Russell Lamour and Jorge Abiague of Portland, and Jimmy Smith, formerly of Biddeford now living in Rhode Island, are on the undercard, as is Brandon Berry from tiny West Forks Plantation.

McDermott doesn’t know their names, only that their common ground is the desire to move ahead in their lives and have the confidence to do it. McDermott wasn’t a contender for the world light heavyweight title. He was a busy New England fighter whose pro record of 52 wins (31 by knockout), 16 losses and three draws is impressive in any era.

He was a draw for promoter Sam Silverman, especially when he fought Pete Riccitelli of Portland, whose flamboyance played off McDermott’s man-in-the-street persona. They were the local Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier rivalry and fought five times. McDermott won two of the five.

They weren’t friendly outside the ring and certainly not inside. Riccitelli died almost penniless in December 1997 of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. He was 54. Russo, who was a young boy running boxing gloves from the ring to the Expo dressing rooms when Riccitelli and McDermott fought, organized a memorial service the following spring.

McDermott, 71, lives in a large retirement community in central Florida called The Villages. He works a heavy bag three times a week. We spoke recently by phone. He sounded well.

He left the Portland area shortly after he married at 16 and fathered a child at 17. “I was the son of Jack McDermott and people didn’t let me forget it. I had to start over somewhere else.”

McDermott said his father was physically abusive, even after his son became a popular fighter. Jack McDermott showed up one night inside his son’s dressing room at the Expo minutes before a big fight. The father slugged him, the punch landing near an eye. Jack McDermott needed to prove he could still beat his son.

“I never touched my father,” said Jim McDermott. “I want you to know that.” That he was telling me something so personal was meant to show what he did with his life.

“I got my GED (general education development diploma) in my 30s. I went to college. I got into local politics (in Massachusetts). I ran for alderman, or city councilor as you would call it. I lost my first two elections by four votes each time.

“I won the next seven. My campaign slogan was simple: “I’ll fight for you, just like I fought for myself.” Powerful words if voters looked at that record.

For the first four years, McDermott fought mostly in Massachusetts. He became a headliner at the Expo around 1966. Silverman paid his fighters in cash. The money came from the box office. Successful fighters like McDermott might have gotten between $800 and $1,200.

“If you lost, you got a couple of hundred less for the next fight. Sam (Silverman) said it was because my value went down. When I won he only gave me $10 or $20 more for my next fight. He said I was supposed to win.”

McDermott took his fight earnings and threw it into a drawer when he got home.

His wife, who could “take a nickel and grow a dime” banked it.

McDermott’s big payday came far away from the Expo. He fought contender Frankie DePaula at Madison Square Garden in 1968.

McDermott was knocked down five times and knocked out in the fourth round.

“I froze. I was in Madison Square Garden. I was so ashamed. But the money helped pay off an apartment house I bought and put a new roof on it.”

“McDermott was a fighter’s fighter,” said Tony Lampron, who fought McDermott once, in 1970. Lampron put himself through what is now the University of Southern Maine with his purse money. Years later he trained Joey Gamache, the world lightweight champ from Lewiston.

“Jimmy was a fearsome competitor with a big right hand,” said Lampron. “I had a pretty good left jab and I outboxed him.”

Lampron won a 10-round unanimous decision and earned $800. But then, his tuition that semester was $350.

“I thought it my crowning fight of my career,” said Lampron. “You know, he spoke to me only once in the time I knew him. It was that night, during the fight. He whispered in my ear: ‘Tony, I heard about your left jab but I didn’t know until now how good it was.’ ”

The decision and the money meant a lot to Lampron at the time. The one sentence McDermott ever said to him meant the world.

Steve Solloway can be contacted at 791-6412 or at:

ssolloway@pressherald.com

Twitter: SteveSolloway

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.