PHIPPSBURG – For months, Dick Hill has been nervously watching the erosion at Popham Beach State Park.

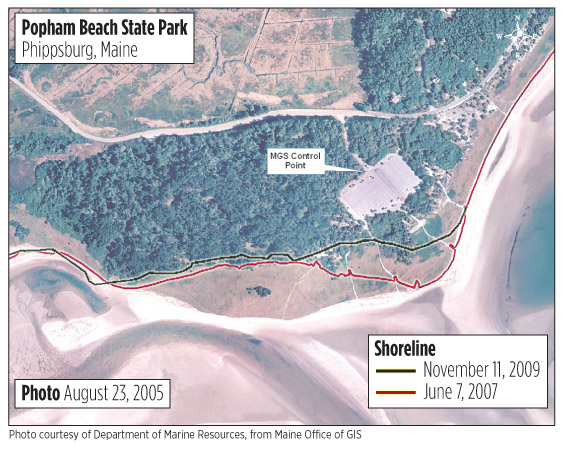

Since November, the shifting Morse River has eaten away the sand dunes to within 25 yards of the park’s bathhouse and septic system, toppling hundreds of trees and further threatening a beach that, for the past few years, has disappeared at each high tide.

Last week, Hill organized a meeting to rally support for a dredge-and-fill operation to put the Morse River back on its original course — a move opposed by abutting landowners.

But this weekend, an unusual trifecta of ocean surf and tides could solve the decades-old erosion of Popham Beach.

”Mother Nature is going to do the heavy lifting for free,” state marine geologist Stephen Dickson gleefully predicted last week.

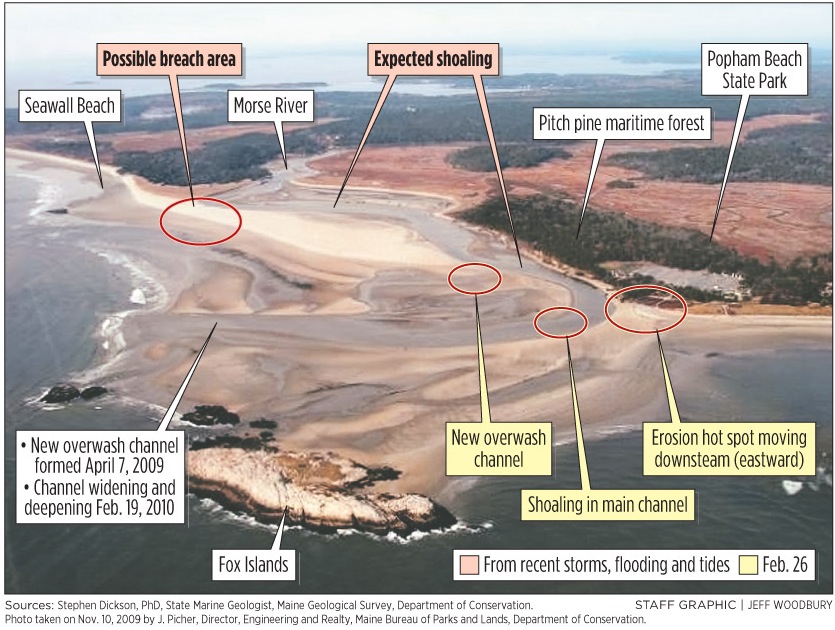

Dickson said the storm system Thursday and Friday created a tidal

surge and pounding surf from 10- to 15-foot waves offshore, followed by astronomical high tides Saturday and today. That may be enough to recut the original channel, which Dickson said would result in a visibly enlarged beachfront with room for sunbathers even at high tide as early as this summer.

”You might see this once in a lifetime,” said Dickson, who has spent his professional career studying the sands at the mouth of the Kennebec River.

The sands at Popham Beach have been shifting since the glaciers departed 20,000 years ago, leaving behind mountains of sand that washed down the Kennebec River to form a beach system unique to the Maine coast. Today, sands extend out several miles along an area stretching from Small Point Beach at the tip of Phippsburg Peninsula to Reid Sate Park at the tip of the Georgetown peninsula on the mouth of Sheepscot River.

The sand bars attract birds. Sand dollars cover the sandy underwater delta. The area is a magnet for winter flounder, which prefer sandy ocean bottoms.

The Morse River, which lies on the western end of three-mile-long Popham Beach, carries the tides from the ocean into the marshes behind the beach. The river channel naturally changes course every 15 years or so, moving eastward and back, from a straight path to the ocean to an angled approach.

”Like a tail on a dog wags back and forth,” said Dickson.

But for the past decade, the tail has continued to wag toward the state park, causing the beach to erode more than at any time in the past century.

A series of easterly storms in the past couple of years has accelerated the erosion. That has pushed the high tide mark inland by about 180 feet — to within 75 feet of one of two new bathhouses that opened last summer, part of a $1.4 million improvement project.

Hundreds of trees fell into the river. With about 10 feet of shoreline vanishing each week, park officials obtained a special permit from the Army Corps of Engineers in November for a project to stem the erosion.

The permit allowed the state to rig a temporary sea wall by bundling the fallen trees and securing them with ropes to others on high ground. The temporary wall has worked.

”We have lost inches rather than hundreds of feet since we did that in early November,” said John Picher, director of engineering and realty at the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands.

At the same time, bureau officials met owners of property abutting the Morse River. They hoped to get permission to cut a channel through the sand bars now blocking the river’s direct outlet to the ocean, and to block off the new channel that has been carved out.

The abutters, including the Bates-Morse Mountain Conservation Area, the Small Point Association and the Nature Conservancy of Maine, said they were not interested in human intervention in the area, preferring to let nature take its course.

Laura Sewall, director of the Bates-Morse Mountain Conservation Area, said it was not clear that cutting a channel would permanently solve the problem, and abutters were worried about how the work would affect wildlife. The conservation area is used for educational research.

”It could not serve as a laboratory that teaches us about natural processes,” said Sewall.

Clammers were equally displeased at the prospect of human interference and the potential loss of clam beds that had been uncovered by the changing course of the river.

”Who is going to pay the clammers for the loss of all of these clams?” asked Richard Lemont, a former longtime Phippsburg Shellfish Committee chairman.

But beachfront residents such as Dick Hill, worried that the Morse River would erode the beach, were anxious to see the channel cut.

”My family has been going to that park since the turn of the last century,” said Hill.

He said if the erosion were to reach the park’s septic systems, the entire beach area might have to be shut down because of the resulting pollution.

Other visitors to the beach — there are 175,000 annually, making it one of the most heavily used state parks in Maine — say it would be great if they no longer were forced to abandon the beach for a couple of hours around each high tide.

”I just want to make sure it is still here so we can use it,” said Susie Reinheimer of Bowdoinham, who was riding her horse, Cody, on the beach last week.

Will Harris, Bureau of Parks and Lands director, said the channel-cut proposal has now been shelved, and moving the building and septic system is not fiscally feasible. No other practical solutions have surfaced.

”We have done pretty much what we can do,” said Harris.

Which means Harris and others are hoping that Dickson is right, and the storms and high tides this weekend will deepen a fledgling channel that has developed and send the Morse River back on a straight course. After Thursday and Friday, several more feet had been eaten into the shoreline, and more trees had toppled near the bathhouse.

But there were signs that the erosion had shifted further east. Dickson said it will be clear by Wednesday, once the high tides wane, whether the river has changed course.

He said the new channel has to be scoured out to a depth greater than the existing channel, like a seesaw. Then the sand will begin to build back on the park side of Morse River.

”It could tip the balance and help save the Popham State Park,” said Dickson.

Staff Writer Beth Quimby can be contacted at 791-6363 or at: bquimby@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.