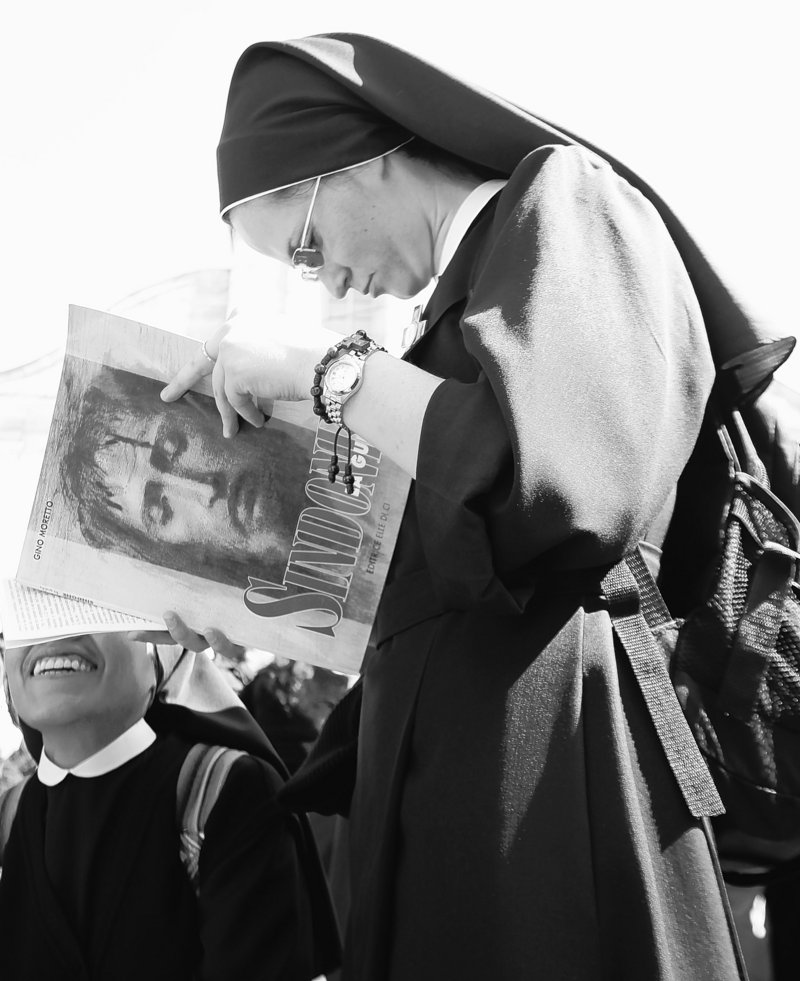

TURIN, Italy — The long linen with the faded image of a bearded man is the object of centuries-old fascination and wonderment, and closely kept under wrap. Starting Saturday, and for the coming six weeks, both the curious and those convinced the Turin Shroud is the burial cloth of Jesus Christ can have a brief look.

late Friday, 1.5 million people had reserved their three-to-five-minute chance to gaze at the cloth, which is kept in a bulletproof, climate-controlled case. Organizers said earlier this year they hoped some 2 million pilgrims and tourists would see the linen during the special viewing from April 10 to May 23.

That number doesn’t include Pope Benedict XVI, who will fly up to Turin, Piedmont’s capital in northwest Italy, on May 2 to pray before the shroud.

Traditionally, the public gets a peek at the 14-foot-long, 3.5-foot-wide cloth only once every 25 years. But recent decades have seen much shorter intervals. The shroud went on display in 1998 after a 20-year wait and then in 2000 during Millennium celebrations.

Church officials resisted putting the cloth on display when tourists poured into Turin in 2006 for the Winter Olympics. But, as city officials recently put it, in a nod to the “importance to the economy and employment” of this city that is automaker Fiat’s hometown, they allowed that this is being billed as the “first showing of the new millennium.”

Since the linen’s previous showing a decade ago, restorers have removed patches sewn on by nuns in 1534, two years after fire damaged the case then holding it, Shroud Museum director Gian Maria Zaccone said in an interview with Associated Press Television News.

Taking off the patches allowed the linen to be fully extended and let restorers smooth out creases in what for centuries had been a rolled-up cloth, making for what restorers hope will be better preservation.

“A challenge to the intelligence” is how John Paul II defined the cloth in 1998 when he journeyed to Turin to view it. In a major papal pronouncement about the shroud, the late pope asked experts to study it without preconceptions using “scientific methodology” while keeping in mind the “sensibility of the faithful.”

His balanced instruction reflected a Vatican tiptoe around the issue of just what the cloth is, calling it a powerful symbol of Christ’s suffering while making no claim of its authenticity.

A Vatican researcher said late last year that faint writing on the linen, which she studied through computer-enhanced images, proves the cloth was used to wrap Jesus’ body after his crucifixion.

But experts stand by carbon-dating of scraps of the cloth that determine the linen was made in the 13th or 14th century in a kind of medieval forgery. That testing didn’t explain how the image of the shroud — of a man with wounds similar to those suffered by Christ — was formed.

However, some have suggested the dating results might have been skewed by contamination and called for a larger sample to be analyzed.

Among those in Turin on Friday for the start of the viewings this weekend was Antonio Lambatti, a professor of Christian history at the University of Parma, who describes himself as a skeptic.

“In my judgment, it’s a fake,” Lambatti told APTN. He cited historical research, specifically a declaration by a church official in 1355 that the cloth was a “representation” of the original cloth.

But the fascination about the shroud “goes beyond history and archaeology,” Lambatti acknowledged. “It implies a choice of faith.”

Besides the 16th-century blaze, the cloth has had other brushes with disasters, including a 1997 fire in the cathedral.

It also might have survived the covetous clutches of Hitler.

In the early weeks of World War II, the cloth was secretly whisked from its resting place in the cathedral to a monastery in Montevergine in the southern Apennine mountains, recalled Rev. Andrea Davide Cardin, director of Montevergine’s state library.

“It wasn’t so much that Hitler was looking for it, but that the Nazi hierarchy wanted it as a symbol of power, of omnipotence,” Cardin said.

Because of a friendship between the monastery’s chief abbot and the Savoys, the Piedmont royal family, long custodian of the shroud, Montevergine was chosen for safekeeping, and a hiding place carved in a wooden altar in a chapel of the abbey, Cardin said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.