When we talk about our own culture, we talk about how we are distinct from anyone else. What we cringe at, however, is culture that goes beyond the simple pride of identity to make insidiously greater claims.

Nazi and Soviet art, for example, pushed past indigenous culture to enlist themselves in propaganda wars.

Yet certainly, the vast majority of art that engages with identity is not propaganda.

Sometimes, identity-oriented art takes the form of documentary — such as the photos of a doomed Brazilian slum by photojournalist Noah Addis. They make for an unusually strong combination of brutal human narrative and simply gorgeous photography.

One image particularly resonated with me: a dark-skinned little girl with a pink backpack and an oversized white baby doll is seen from behind scampering over garbage and through a ruined and empty slum — a maze of broken walls, filth and crumbled building materials. She is heading through ever darker passages.

For us, the scene is almost inconceivably nightmarish, but for her, it’s simply the way home.

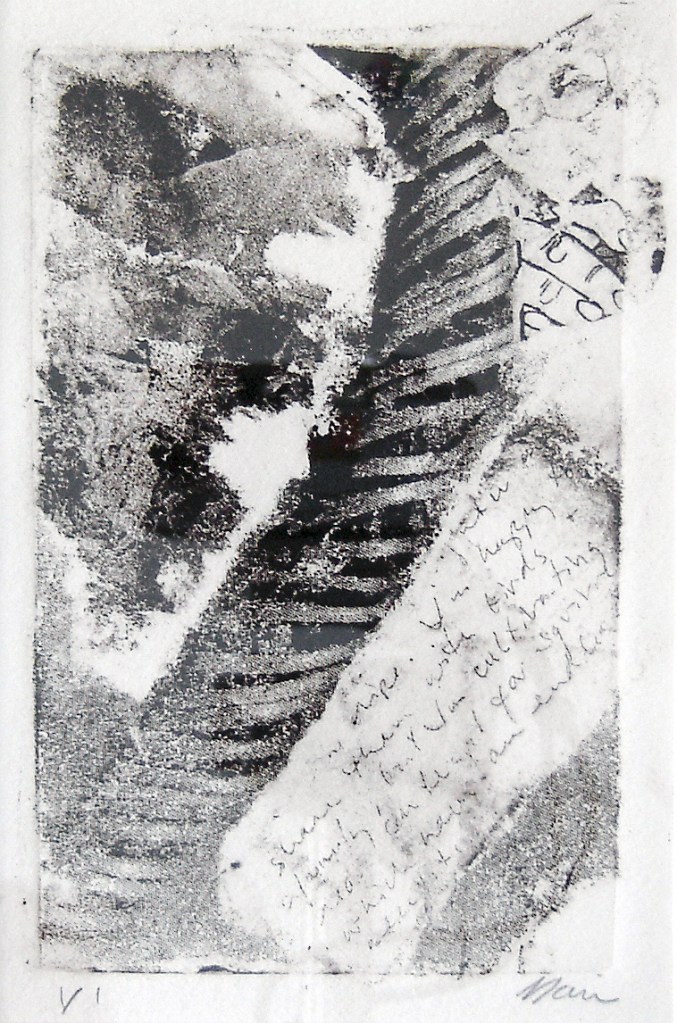

An unusually innovative, honest and engaging show of identity-oriented art is Marin Magat’s exhibition at Running With Scissors, “The Last Magat?” In it, the artist shows works by herself and three previous generations of women who have carried the Magat name.

In prominent label copy, Magat openly explains how the women in her family have been the artists while the men have passed on the name. The Bates College graduate informs us how she has chosen not to take her husband’s name and muses about what will happen when they have children — since she is the last of her named line.

While Magat shows some real promise as a printmaker, her exhibition virtually explodes with the conceptual and cultural potential of her straightforward questions.

With his exhibition, “Genderwork,” Jack Montgomery joins Addis and Magat in revealing that poignantly unanswered questions are often a vehicle for compelling art.

A great photographer, Montgomery is a straight-talking, 60-year-old father from Freeport with several adult children. His take on identity exudes not only the calmly broad acceptance that Mainers have, but that distinctively fatherly combination of deeply protective warmth coupled with a razor-sharp eye.

Considering that Montgomery is shooting people he isn’t sure he should describe as transgendered, cross-dressers or something else, his respect for his few models is almost shockingly apparent.

“Genderwork” at Susan Maasch may be bold and brilliant, but it is a small show, and Montgomery seems to be a master of this scale. He makes the point that the more we see, the more we learn about someone — but this master of empathy also lets us know that the fundamentals of humanity are at hand even in a single encounter.

Montgomery presents portraits of “Goldie” both in 2002 and more recently. Portrait photography contains a large element of theatricality, and Montgomery clearly welcomes this as the site of collaboration.

While theatricality is almost always a negative for me, here it is about empowerment rather than artifice by allowing for the agency of the subject.

We see Goldie in profile flexing a fit arm swathed only in feathery tattoos — vital and gendered, but illegibly so. We see Goldie years later play both sides in equally compelling and equally beautiful photos: showing off a bright red Spanish dress and plopped confidently back in a director’s chair — blue suit, blue eyes, drawn-on goatee, cowboy boots and the most cavalier posture imaginable.

The theatrics, however, are not studio tricks. They are elements of Goldie as a real person. Montgomery’s touch is masterful, just enough to remind us he’s there to bring light on the scene rather than pull any curtains over our eyes.

The most interesting piece in the show is a large-scale print masquerading as a proof sheet. It’s like a cross-section, but cut the long way.

We see old and new together, acting as though they were all shot at once. While the large-scale photos are gorgeous and worthy in this faked proof sheet, we feel Montgomery’s exquisite thoughts on identity teeter and totter between the seen and the unseen.

They hint that we should value what we don’t know as much as what we know.

For a nation of individuals, Montgomery’s work is an elegant reminder that we shouldn’t be afraid of diversity — or empathy.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.