I love going to exhibitions by graduating artists to see the new crop of talent and get an idea about what’s going on with particular programs.

The exhibition of works — painting, film, photography, drawing, printmaking and installation — by 16 senior art majors on view in the Bates College Museum of Art is rich and ranging. It shows intelligence and talent, along with a whole pack of interesting flaws.

Student work is literally made for criticism (by the instructor, class “crits,” grades, etc.), so it’s easy to approach with questions about content and whether or not it is successful. Instead of insisting that you revere the work (like in a museum) or admire the work (like in a gallery) or enjoy the work (like in a friend’s home), art in thesis shows tends to exude a message akin to: “Here’s what I did: What do you think?” I like that direct humility.

I was most impressed with the two animated film artists. Both have cryptic pieces about children, which is ironic because it is the only work not particularly suitable for children in an otherwise great show for the family.

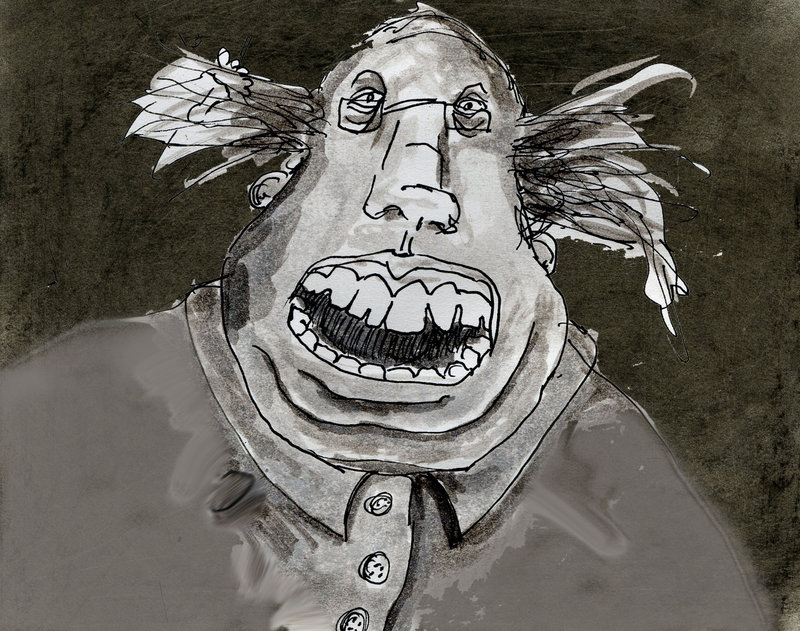

Kelly Gollogly’s “The Boy Who Could Not Not Worry” is a bow to creepy children’s books along the lines of Edward Gorey. It is the story of a pathologically anxious child who seeks a mechanical cure for his gloom from a weird inventor. The boy is appalled by the inventor and finds the confidence he previously lacked in deciding to stand up for himself and reject the treatment.

Some of Gollogly’s ink-and-wash drawings are terrific, and she makes great use of them in a minimally animated approach tied to online children’s books and edgy online animation. Her accompanying statement, however, makes a claim that could offend a bunch of people — that mental illness is on a “spectrum” and we each have control of “our own mind.”

In fact, the artist statements (mounted as label copy) are the worst thing about the exhibition as a whole, but it’s still interesting to read them. The artist may have put only 1 percent of her time into the statement, but the casual viewer might let it count for most of her understanding of the work. I thought Allison Spangler’s series of nudes seen from behind standing outside in the snow was terrific — but her statement’s weakness took it down a few notches for me.

The best statement was Matthew Reynolds’ case for experience over narrative, in which he notes: “I am not interested in posing questions of meaning to my audience.” His film “Rescue Party” was as innovative and strong as it was disturbing. I hesitate to discuss how this film unfurls, because what appear to be mistakes (like an inverted reflection) later reveal brilliantly subtle meaning when the piece suddenly flips from silly to brutal. Reynolds is a guy to watch.

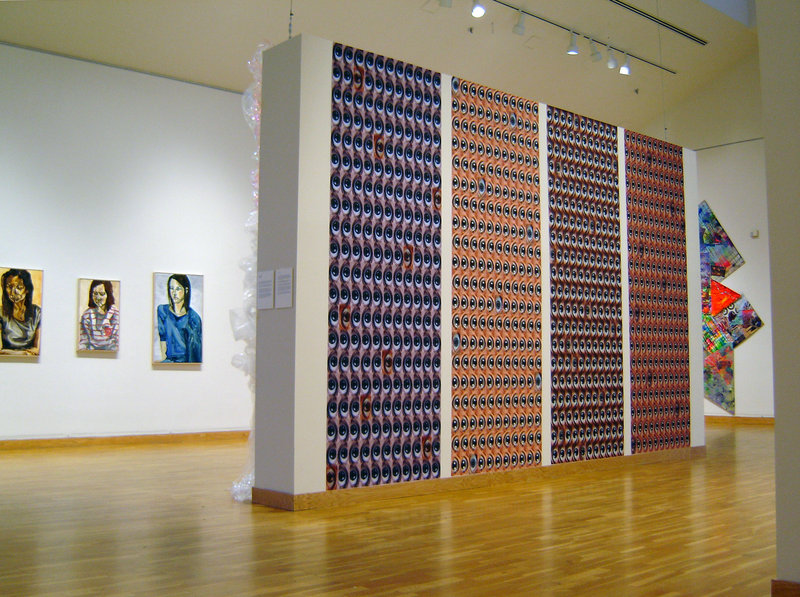

There is much enjoyable work: Lisa Hartung weaves digital photos of eyes into dense wallpaper with ocular columns snaking from floor to ceiling. Olga Grigorenko’s surprisingly elegant flyswatter prints on telephone book pages smartly muse on how the modernist grid — or any grid — is defined not by its lines but by the marginal spaces between them.

Annie Connell’s beautifully finished ink on vellum “splayed series” drawings feel like life-sized images of the body revealed for surgical procedure. Heidi Judkins’ wall installation of bubble wrap and other industrial materials delivers a clear message and the boldest visual presence in the show.

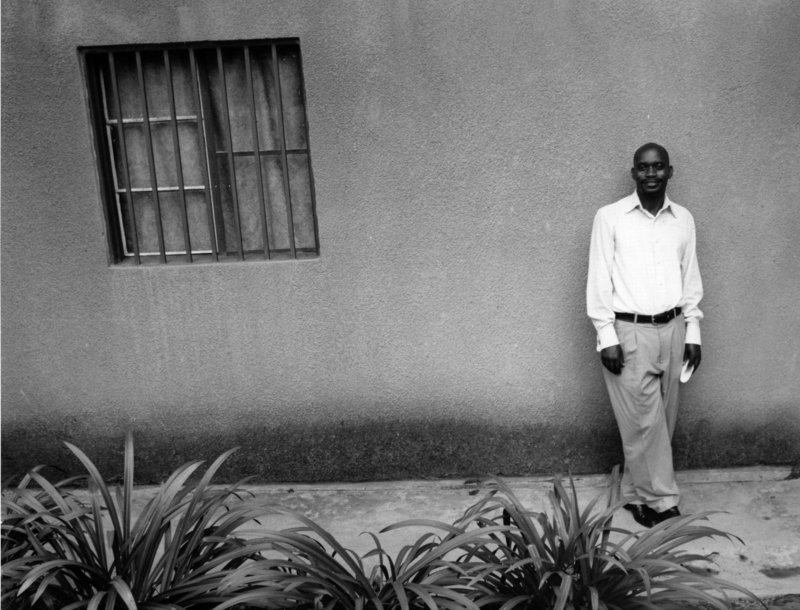

Emma Scott’s scattered photographic portraits of people orphaned by the Rwandan genocides are pulled together by handwritten letters from their subjects. One, written by “Elise” in flowing French, has been haunting me since I read it: “Mais vivre avec les blessures, c’est le combat de chaque jour.” (“But to live with these wounds is to face combat every single day.”)

Even the work I didn’t particularly like was fun to consider. Sarah Ewing’s close-up photographs of necks and shoulders just don’t warrant her comment: “I like shocking and provocative art.” Elizabeth Denham writes: ” ‘Crappy’ and ‘pop’ are really the only words I can use to describe my aesthetic” — it’s a tongue-in-cheek dare, but unfortunately apt.

I don’t know if there are future superstars among them, but the Bates art majors are a pack of smart, young people with talent and ideas who are presenting an interesting and enjoyable show.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.