ORRINGTON – At this time of year, the Penobscot River flows dark and deep, draining the second-largest watershed in New England — and one of the most pristine.

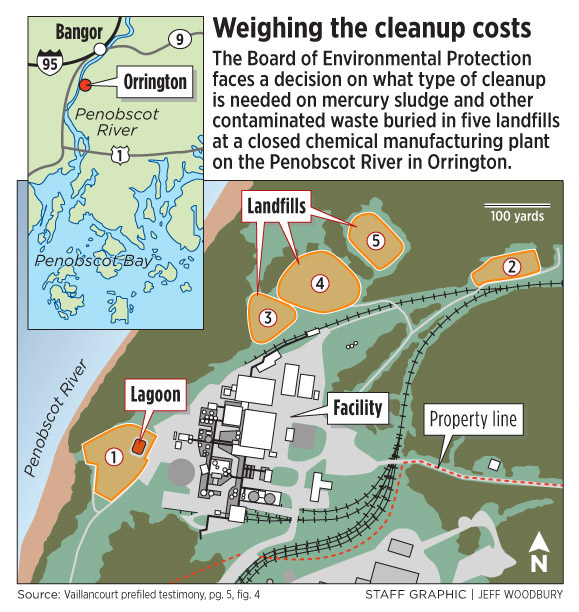

But as the river passes through the town of Orrington, it picks up an added ingredient: mercury leaking from five landfills on the riverbank at the former HoltraChem Manufacturing Co. plant. The polluted water then flows past Bucksport and into Penobscot Bay, past the coastal tourist towns of Castine, Camden and Rockland, the big summer homes on the islands of Islesboro, North Haven and Vinalhaven, and into the fishing grounds of the Gulf of Maine.

“This is not just an Orrington issue. This river is so valuable to Maine’s economy,” said Ryan Tipping-Spitz of Bangor, an organizer with the Maine People’s Alliance, an advocacy group that has been pushing for a cleanup at HoltraChem for decades.

The mercury contamination at the plant, once described by Gov. John Baldacci as the worst hazardous waste site in the state, has been the focus of a cleanup effort dating to the 1980s.

Now, the extent of the cleanup lies in the hands of the Board of Environmental Protection. It will meet Thursday to consider two approaches.

One, backed by its own staff in the Department of Environmental Protection, would order Mallinckrodt LLC, the company responsible for the site, to remove all five contaminated landfills at a cost of $250 million. The other, proposed by the company, would remove one landfill, at a cost of $100 million, and leave the rest.

At issue is whether the mercury contamination can be left safely in the ground or whether removing it all is the safest solution. For many of the 3,622 residents of this Bangor suburb, those questions still have no clear answers — despite years of study by government regulators and private consultants.

“Does anybody really know?” asked Lee Washburn, who has lived next to the plant since 1991.

The chemical plant opened in 1967 on 235 wooded acres next to the river. It was owned by International Minerals and Chemical Corp., which later became the Mallinckrodt Group, a Hazelwood, Mo., subsidiary of Covidien, a global health company.

The plant manufactured chlorine, caustic soda and chlorine bleach for the paper industry, using a manufacturing process that used mercury. Sludge left over from the process, containing mercury and various chemical compounds, was buried in five landfills on the site until 1981.

Mallinckrodt sold the plant in 1982. The plant’s last owners, HoltraChem, are no longer in business, so Mallinckrodt is the only operator of the plant left to pick up the cleanup costs.

Mercury released from the HoltraChem plant washed into the sediments of the river and has been detected in the tissue of fish. Almost all human exposure to mercury, which can damage the brain and kidneys, is through fish consumption.

Eels, lobster, Nelson’s sharp-tailed sparrows and other wildlife in or near the Penobscot — especially near the plant site — have higher mercury concentrations than populations in any other river in Maine.

So far, Mallinckrodt has spent about $40 million on the site. Most of the buildings and 1 million pounds of contaminated soil have been removed, and a treatment system has been installed to extract mercury from the groundwater.

The Maine People’s Alliance and the Natural Resources Council of Maine, the state’s major environmental advocacy group, sued the company in federal court. A judge ordered Mallinckrodt to fund a two-part, $4 million independent study to determine the feasibility of cleaning up mercury contamination downriver from Orrington. That study is still under way.

The next step is to deal with the 80,000 pounds of mercury remaining in the landfills.

In 2008, the DEP ordered the company to remove all 360,000 tons of contaminated soil. Mallinckrodt appealed the order, and the matter was sent to the Board of Environmental Protection, a group of 10 laypeople who review appeals of DEP decisions. The board, appointed by the governor, had never handled a case involving such a potentially expensive cleanup.

The hearing last winter involved two weeks of testimony from expert witnesses, as well as representatives from the town of Orrington and the Maine People’s Alliance. Mallinckrodt’s witnesses include Woodard and Curran, a Portland-based environmental firm hired by the company to review cleanup alternatives.

Woodard and Curran recommended removing the landfill closest to the river — which all parties agree on — while leaving behind the four remaining landfills, which the engineers deemed stable.

At the same time, the company made a number of pledges to the town, agreeing to take ownership of the 12 contaminated acres that have been in the town’s possession since HoltraChem shut the plant down and dissolved the business.

Mallinckrodt said it would set aside an unspecified amount of money to cover the ongoing cost of monitoring the site and help the town develop roads and water lines on the rest of the parcel, which the town wants to turn into an industrial park.

The DEP argued that no one can predict whether the landfills, none of which meet today’s minimum standards, will remain stable. The department said tests show groundwater is still filtering into several of the landfills.

The state experts argued that removing the soil, using methods that would not release mercury into the atmosphere, and taking it to a special waste center is the only permanent way to ensure that the mercury does not continue to leach into groundwater and the river.

As part of the hearing process, the board asked the Orrington Board of Selectmen to indicate which plan was the most acceptable. Selectmen heard presentations from both sides and unanimously voted in favor of Mallinckrodt’s proposal.

Chairman Howard Grover said he trusted the data presented by Woodard and Curran, and it made sense to accept the company’s offer now. Grover said he was concerned that Mallinckrodt, which created a new subsidiary that is now the entity responsible for the cleanup, doesn’t have the assets to cover the larger, $250 million project.

The company denies the new subsidiary has anything to do with the Orrington site, but it declined to say whether it can afford the more expensive cleanup.

“We have been committed, we remain committed. Our focus is, ‘What is the right thing to do from an environmental standpoint?’” said JoAnna Schooler, company spokeswoman.

Company officials say they have worked hard to keep the community informed of the cleanup’s progress, sending out newsletters and speaking directly to the town for more than two years.

“We really believe we have an obligation to this community about what we had been doing for the past 10 years,” said Schooler.

Residents upset with the selectmen’s vote collected enough signatures to force a referendum.

In the weeks leading up to the vote, Mallinckrodt and the Maine’s People Alliance launched vigorous campaigns with door-to-door canvassing and mailings. On April 23, a voter turnout of 27 percent backed the company plan, 381-357.

Orrington resident Danielle D’Auria, mother of a 2-year-old daughter, voted for the DEP proposal.

“DEP has nothing to gain or lose by proposing this full cleanup plan, whereas the company obviously has money to lose,” said D’Auria.

Other residents wondered whether the five- to six-year cleanup sought by the DEP would create more pollution from the digging, despite assurances by the state that it would not.

“It comes down to, ‘Do you believe landfills that are behaving at this time?’” said Washburn, the plant neighbor who voted for the company proposal.

Others said the vote was divisive.

“To me, nobody wins. All it does is split people up,” Grover, the selectman, said of the referendum.

The board is set to begin its deliberations Thursday. The process should entail several sessions in the next few weeks, before the board takes a vote and drafts an order. Both the DEP and Mallinckrodt may then comment on the order before the board issues a final ruling.

Either side can appeal to Superior Court.

DEP Commissioner David Littell has said he expects that is what Mallinckrodt will do if the board orders all the soil removed.

“It is much less expensive to pay attorneys to fight the remedy than to actually clean up the site,” said Littell.

Schooler said her company will continue to push for its proposal.

Tim Conmee, an Orrington resident and member of the Maine People’s Alliance, said he is not optimistic that the cleanup will end happily for taxpayers.

“We will be stuck with the bill anyway,” he said.

Staff Writer Beth Quimby can be contacted at 791-6363 or at:

bquimby@pressherald.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.