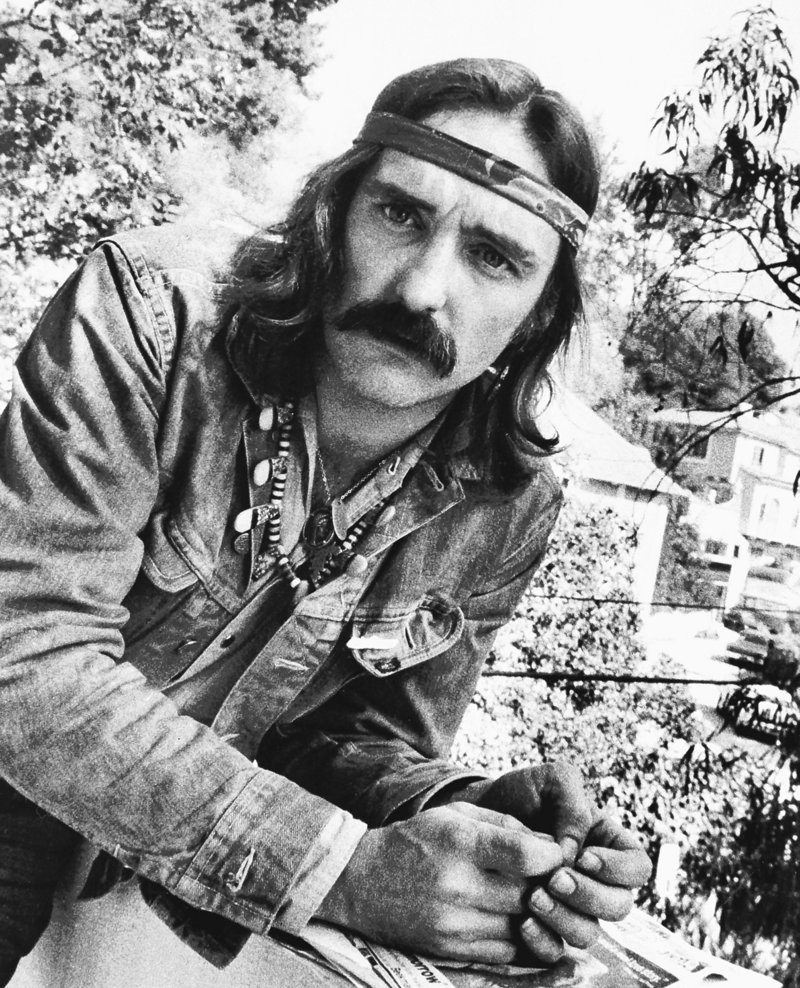

LOS ANGELES – Dennis Hopper, the high-flying Hollywood wild man whose memorable and erratic career included an early turn in “Rebel Without a Cause,” an improbable smash with “Easy Rider” and a classic character role in “Blue Velvet,” has died. He was 74.

Hopper died Saturday at his home in Venice, Calif., surrounded by family and friends, family friend Alex Hitz said. Hopper’s manager announced in October 2009 that he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer.

The success of “Easy Rider,” and the spectacular failure of his next film, “The Last Movie,” fit the pattern for the talented but sometimes uncontrollable actor-director, who also had parts in favorites such as “Apocalypse Now” and “Hoosiers.”

He was a two-time Academy Award nominee, and in March, he was honored with a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame. But after a promising start that included roles in two James Dean films, Hopper’s acting career languished as he developed a reputation for throwing tantrums and abusing alcohol and drugs.

Married five times, Hopper led a dramatic life to the end. In January, he filed to end his 14-year marriage to Victoria Hopper, who stated in court filings that the actor was seeking to cut her out of her inheritance, a claim Hopper denied.

SUCCESS WITH ‘EASY RIDER’

For “Easy Rider,” Hopper collaborated with another struggling actor, Peter Fonda, on a script about two pot-smoking, drug-dealing hippies on a motorcycle trip through the Southwest and South to take in Mardi Gras in New Orleans.

On the way, Hopper and Fonda befriend a drunken young lawyer (Jack Nicholson, whom Hopper had resisted casting, in a breakout role), but they arouse the enmity of Southern rednecks and are murdered before they can return home.

Fonda produced “Easy Rider” and Hopper directed it for a meager $380,000. It went on to gross $40 million worldwide, a substantial sum for its time. The film caught on despite tension between Hopper and Fonda and between Hopper and the original choice for Nicholson’s part, Rip Torn, who quit after a bitter argument with the director.

The film was a hit at Cannes, netted a best-screenplay Oscar nomination for Hopper, Fonda and Terry Southern, and has since been listed on the American Film Institute’s ranking of the top 100 American films. The establishment gave official blessing in 1998 when “Easy Rider” was included in the United States National Film Registry for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

Its success prompted studio heads to schedule a new kind of movie: low-cost, with inventive photography and themes about a young, restive baby boom generation. With Hopper hailed as a brilliant filmmaker, Universal Pictures lavished $850,000 on his next project, “The Last Movie.”

The title was prescient. Hopper took a large cast and crew to a village in Peru to film the tale of a Peruvian tribe corrupted by a movie company. Trouble on the set developed almost immediately, as Peruvian authorities pestered the company and drug-induced orgies were reported.

When it was released, “The Last Movie” was such a crashing failure that it made Hopper unwanted in Hollywood for a decade.

A LIFE OF COMEBACKS

Shunned by the Hollywood studios, he found work in European films that were rarely seen in the United States. But, again, he made a remarkable comeback, starting with a memorable performance as a drugged-out journalist in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 Vietnam War epic, “Apocalypse Now.”

He went on to appear in several films in the early 1980s, including the well-regarded “Rumblefish” and “The Osterman Weekend.”

But alcohol and drugs continued to interfere with his work. At one point he became so hallucinatory that he was committed to the psychiatric ward of a Los Angeles hospital.

Upon his release, Hopper joined Alcoholics Anonymous, quit drugs and launched yet another comeback. It began in 1986 when he played an alcoholic ex-basketball star in “Hoosiers,” which brought him an Oscar nomination for best supporting actor.

His role as a wild druggie in “Blue Velvet,” also in 1986, won him more acclaim, and years later the character wound up No. 36 on the AFI’s list of top 50 movie villains.

POLITICS UNPREDICTABLE

He returned to directing, with “Colors,” “The Hot Spot” and “Chasers.”

From that point on, Hopper maintained a frantic work pace, appearing in many forgettable movies and a few memorable ones, including the 1994 hit “Speed,” in which he played the maniacal plotter of a freeway disaster.

For years he lived in Los Angeles’ bohemian beach community of Venice. In later years he picked up some income by becoming a pitchman for Ameriprise Financial, aiming ads at baby boomers looking ahead to retirement. His politics, like much of his life, were unpredictable. The old rebel contributed money to the Republican Party in recent years, but voted for Barack Obama in 2008.

Hopper also tried his hand at a number of artistic pursuits including photography, sculpting and painting. His art, dating to a 1955 painting, is the subject of a show opening July 11 at the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Geffen Contemporary space in downtown Los Angeles. The title of the exhibition, “Double Standard,” is taken from a 1961 Hopper photograph of two Standard Oil signs seen through an automobile windshield on historic Route 66 in Los Angeles.

Dennis Lee Hopper was born in 1936, in Dodge City, Kan., and spent much of his youth on the nearby farm of his grandparents. He saw his first movie at 5 and became enthralled.

After moving to San Diego with his family, he played Shakespeare at the Old Globe Theater.

Scouted by the studios, Hopper was under contract to Columbia until he insulted the boss, Harry Cohn. From there he went to Warner Bros., where he made “Rebel Without a Cause” and “Giant” while in his late teens. Later, he moved to New York to study at the Actors Studio, where Dean had learned his craft.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.