MONTCLAIR, N.J. – After careers in human resources and business consulting, Marianne Bays is tired of the corporate world. The 57-year-old’s choice for a change: trying to become one of New Jersey’s first legal pot dealers.

In January, New Jersey became the 14th state to allow the sale and use of medical marijuana. The law goes into effect July 1, but it’s expected to take several months before the state has regulations in place and the “alternative treatment centers” where patients will be able to get cannabis.

For now, Bays and others — perhaps dozens of them — are quietly setting up nonprofit groups that will apply to run the first treatment centers in the most populous state outside California to allow medical marijuana.

Bays has been telling family and friends about the new career, which she is planning when she’s not working her temporary job helping run the Newark office for the U.S. Census.

“So far, nobody’s looked at me and said something negative to me about it,” said Bays, who has a doctorate in business organization. “They’ve laughed.”

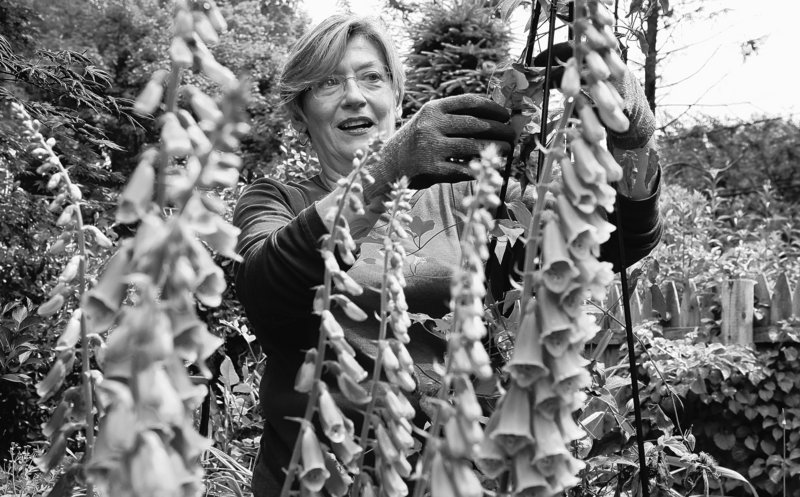

The buttoned-down Bays doesn’t fit the “Pineapple Express” stereotype of a bud purveyor. She loves gardening, but the only herbs she grows are culinary — like rosemary and basil.

She and her husband live in a spacious home in Montclair, a famously open-minded New York City suburb. She says marijuana has always been available in her social circles. But she said school and work never left her much time to indulge.

Over the last few years, she’s learned that some family and friends have found marijuana to ease symptoms associated with conditions from multiple sclerosis to migraines. The drug is used to treat pain, nausea and lack of appetite.

She threw herself into learning more, including classes at Oaksterdam University, an Oakland, Calif., school dedicated to the pot business. She’s also traveled in California with a friend — who suffers from multiple sclerosis — who was able to go into pot dispensaries because of her condition. Bays would wait outside, then quiz her friend about the operations.

Another of the likely marijuana provider applicants in New Jersey is Anne M. Davis, a lawyer who also consults with several people interested in opening treatment centers.

She says she’s hearing from current drug dealers who want to go legit, caregivers who already procure marijuana for the sick, and career changers — especially commercial real estate agents who have fallen on slow times. Some of the dispensaries in California, where medical marijuana laws are less restrictive, are looking into opening branches here, Davis said.

There are people with smart business plans and people experienced with growing the plants — illegally, of course.

“They think, ‘Hey, I’m going to open this great business and I’m going to make a fortune,’” Davis said. “But that’s not what it’s going to be. It’s going to be very strictly regulated in New Jersey.”

Those regulations are not yet written, and Gov. Chris Christie, who says he supports the medical marijuana bill, is trying to win a delay to give his administration extra time to write them.

Still, the state’s new law offers a glimpse at how the clinics will operate.

It requires at least six nonprofit groups be given the first licenses. They must be spread around the state. Subsequent clinics could be for-profit.

Unlike other states, New Jersey will not allow patients to grow their own. Instead, that will be handled by the centers that distribute marijuana. Patients will be tracked and allowed to buy only 2 ounces per month.

Only doctors who have ongoing relationships with the patients will be able to approve marijuana use for them. Only people with certain medical conditions will be allowed to use. Cancer, glaucoma and any prognosis that gives the patient less than a year to live are on the list; headaches are not.

Bays and another potential treatment center operator, Joseph Stevens, both say they would have their growing operations located away from the treatment centers for security reasons. Their business plans call for growing indoors so that harvesting can be done year-round.

Stevens said town officials in the place he wants to operate have accepted the idea, but he’s not yet ready to say where it would be.

Pretty much the only thing he’s made public so far is a logo for his establishment, called The Health Clinic and bearing the not-so-subtle motto: “A HIGHER standard of care.”

Stevens, 37, said that 15 years ago, when his father was dying from non-Hodgkins lymphoma, a doctor suggested marijuana to ease the pain. His dad refused because it was illegal. Stevens thinks his father may have tried it if it were legal.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.