The “Mill-ennial” is a juried exhibition for artists connected to the Saco, Biddeford and Old Orchard Beach area. The organizers hope this will be a continuing biennial: This first incarnation makes a great case that the project will not only survive, but thrive.

The juror for the Mill-ennial was Saco’s own Fred Lynch: a painter and art professor (USM, Colby, Haystack) whose concurrent solo exhibition will be on view at the Portland Museum of Art through July 11.

While Lynch’s name brings credibility and prestige to the Mill-ennial, his eye delivered the real goods: 61 strong works by 39 artists.

The theme of the show is simple enough, and Lynch chose quality and achievement regardless of medium. The Mill-ennial includes painting, photography, assemblage, sculpture, fiber, ceramics, paper, installation and other media that range from representational to abstract, political, expressionist, whimsical, technical, decorative, serious and more.

The show breathes and flows in its space at the Saco Museum. Jessica Skwire Routhier — the museum’s director — installed the show. (Her show “Making History: Art and Industry in the Saco River Valley” is also terrific).

Because of the range of subjects and media in the Mill-ennial, it would be misleading to try to encapsulate it in some glib turn of phrase. What Lynch and the included artists achieve, however, is palpable: a persuasive portrait of a highly accomplished, intelligent and ambitious local art community.

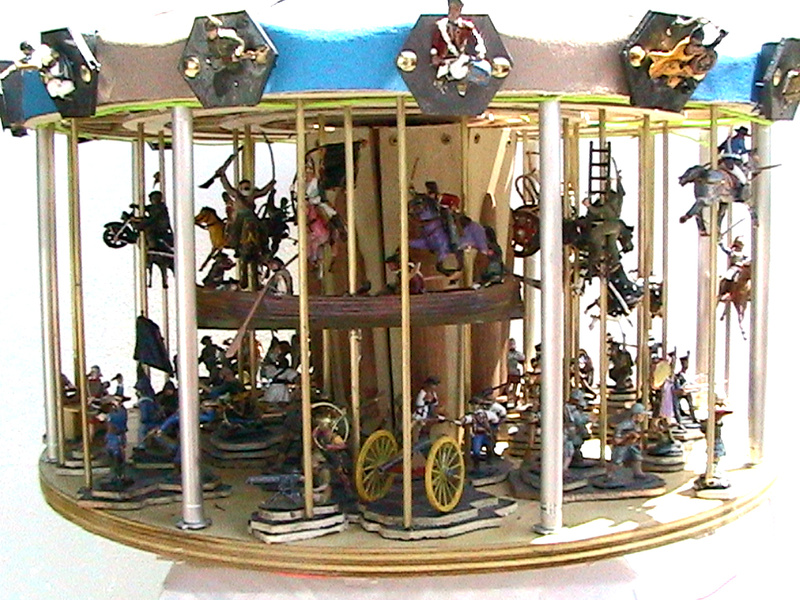

Lynch gave his juror’s award to Omer Gagnon’s “Carasoul of War” — a sparky merry-go-round featuring scores of toy soldiers battling with just enough exuberance to reach the uncomfortable. The piece is difficult to pin down: Is it a boy’s fantasy toy flourishing the heroic pomp of battlefield pageantry? Or is it a broader message that war will keep us going around in circles over and over again in endless cycles void of achievable destination?

Lynch seems to go with the visually smart, so, for most viewers, the ?-toy versus cynical commentary question about this unusual piece will probably not fall on the political side.

The strongest part of the show is the back wall of the Saco Museum. It might seem bleak, but it contains much of the show’s most ambitious and serious work.

The grittiest presence is Deborah Randall’s “Dry Land” — an intense tableau of a ploughed field with a dinghy plopped on the tilled foreground. The paint — knifed on with grimly audacious power — shows threatening skies over an apparently war-stricken landscape. The oar-less boat seems to be more of a reminder to build an arc in times of pestilence than any hint of helpful water.

Kelly Sue Rioux’s “Until I am bones (Adam and Eve)” presents the first-ever couple in a huge, heavy frame as dual marriage portraits separated by an apple-decorated canvas. Adam looks toward the pretty Eve, but her coquettish gaze is decidedly fixed on the viewer. Her assertiveness is presented as the original sin — an unflinchingly tough take on a tender subject.

Donna Caron’s huge concrete sculptures tower as figurative monoliths. Each stands on a single leg — armless, headless and pocked with shells and seaside detritus: ageless ocean guardians, spare and severe.

My favorite work of the bleak corner is Tanya Fletcher’s “Apple” — a dark brown, photorealistic oil painting (made reductively by removing paint to reveal lighter areas) of a huge hand holding a humongous apple in perfect profile. The four panels come together to reveal a coolly elegant image — relaxed and confidently appealing.

There are too many excellent works to list here, but some that stand out are Rick Green’s exquisitely dense encaustic topographical view of a Maine island; Pat Campbell’s double-layered and swirling rice paper “Mandala” of flickering waves; Meryl Ruth’s hysterically smart lobster teapot — with the guts to hold itself up by a pop/kitsch ’80s checkered handle; Nancy Bell Scott’s sharply composed book cover collages; and Anastasia Weigle’s smartly crafted assemblages that suavely lead from the historical through the personal and into the creepy.

The major flaw of the Mill-ennial is its bifurcated imbalance. After the handsome installation at the Saco Museum, the works of George Hughes (which, for me, tilt Lynch’s take on Gagnon to the political) and Celeste Roberge in the North Dam Mill feel ignored like an embarrassing appendage: They seem swallowed by the huge space and installed as though an afterthought. While the works themselves are interesting, trekking to see them after the main show was deeply disappointing. Maybe next time the Mill-ennial should take over the whole space for a shorter run with installations and a Salon des Refus? (or something). Whatever happens, no part of the show should feel so half-hearted.

Still, the exhibitions in the Saco Museum are definitely worth seeing, and I absolutely hope to see the Mill-ennial for years to come.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.