WISCASSET – Thomas Reis slowly piloted a 31-foot boat last week under a rusty railroad bridge that spans the Sheepscot River, north of this scenic village. Back and forth he went, in and out between the granite piers. It looked like Reis was searching for something under water.

In a sense, he was.

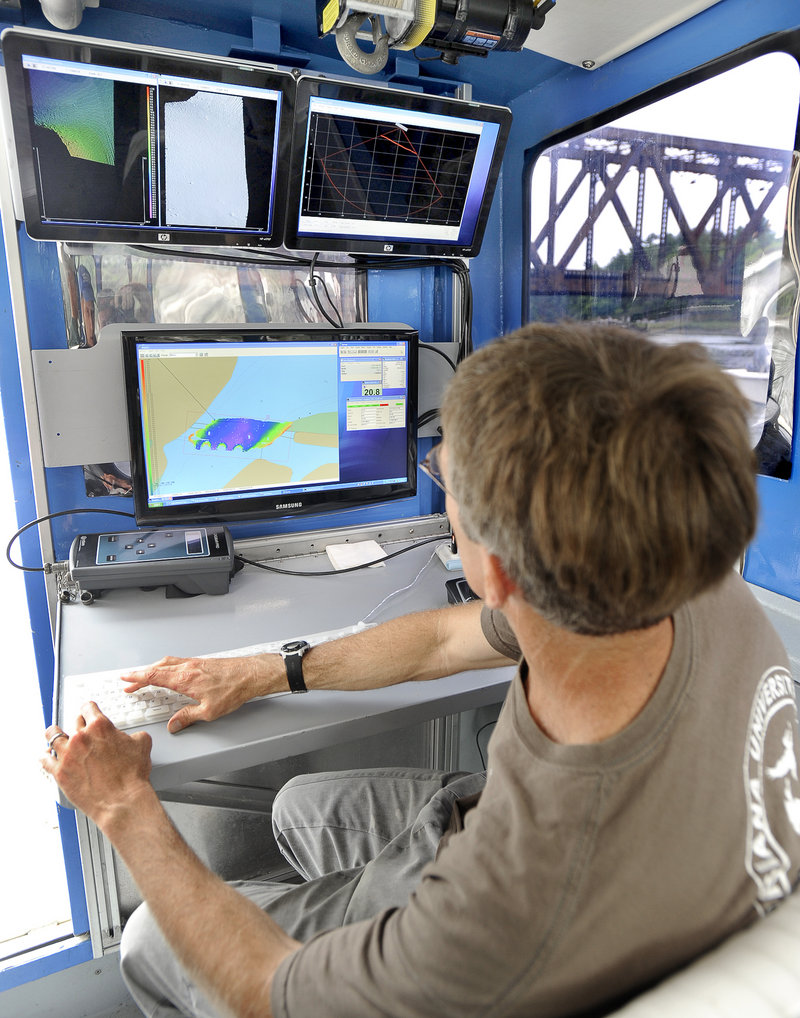

Attached to the hull of Orion, the custom-built survey vessel, is a sophisticated sonar device that can read and map the underwater environment with great precision. Inside the pilot house are computer screens and monitoring devices that capture and decipher what the sonar is seeing.

Orion was gathering information to help determine whether the old railroad bridge, which carries tourist trains along the coast, is at risk of collapsing into the river.

For the second summer, the Maine Department of Transportation has hired Substructure Inc. of Portsmouth, N.H., and Reis, its president, to look for trouble spots at bridges where it’s too dangerous for divers. The work offers a glimpse at how the department ensures the safety of about 500 bridges that cross deep water, and how new technology is playing a role.

Drivers may recognize an aging bridge by rusting metal or a deteriorating deck. What they can’t see, on a bridge that crosses water, is the condition of the piers and footings below them. There’s no way to see whether fast-moving water has eroded the stream bed and undermined the foundations of the piers or abutments, a condition called scour.

Scour is a big deal. In 1987, the Schoharie Creek Bridge, carrying the New York State Thruway, collapsed when its foundations were undermined after record rainfall. Ten people died. The accident prompted better bridge design and inspection, including a federal requirement that spans crossing water be checked at least every five years.

“That’s how most bridges in the country are lost, through scour,” said John Buxton, who heads the Maine Department of Transportation’s bridge maintenance division.

Scour can be subtle, Buxton said. Rivers typically flow faster around piers, the in-water supports, and abutments, which hold up the ends of a bridge. A storm can scoop out a stream bed, creating what’s known as a scour hole. That hole can later fill with sediment and be hard to detect.

Maine has 3,900 bridges over public ways. The state inspects more than 2,000 a year.

Bridges over shallow water can be inspected by workers wearing waders. Deep-water crossings are scrutinized by divers. But in some places, poor visibility, strong currents and deep water make the divers’ job hazardous and hard to do well.

Last year, Maine began using Substructure to inspect three challenging spans on the Kennebec River: the Kennebec Bridge in Richmond, and the Sagadahoc and Carlton bridges in Bath. Those jobs cost a total of $18,000.

“It’s pricey but worth the investment,” Buxton said.

Orion, the survey vessel, is outfitted to create high-resolution underwater images that can be used in dredging, habitat assessment, search and recovery operations, and evaluating structures such as bridges and jetties.

The Sheepscot River railroad bridge is upriver from the span that carries Route 1 between Wiscasset and Edgecomb. It’s owned by the state and leased to the Maine Eastern Railroad.

Orion’s crew began its work last week at low tide, a time when it’s easier to squeeze under the bridge.

On board was Carl Edwards, who heads the Department of Transportation’s dive team. His crew goes under water to inspect more than 120 bridges each year.

Edwards knew of multibeam sonar surveys, but didn’t know that a company in the area was doing the work until he met Reis a couple of years ago. Maine expects to use the technology only in the most extreme dive conditions, Edwards said, because it is expensive.

“But it eliminates the risks of putting a diver down and gives us a better picture,” he said.

Inside the pilot house, Tom Waddington, the company’s senior scientist, sat at a keyboard and a bank of computers. He could see the water depths represented by shades of color, an important indicator of scour holes.

Reis steered Orion in an overlapping course around the abutments and piers. By moving back and forth away from the four piers, the equipment could map the river bottom, where scour is most likely.

The sonar soundings are done in conjunction with a Global Positioning Satellite survey point, so Substructure can produce maps of the underwater environment with an accuracy measured in centimeters.

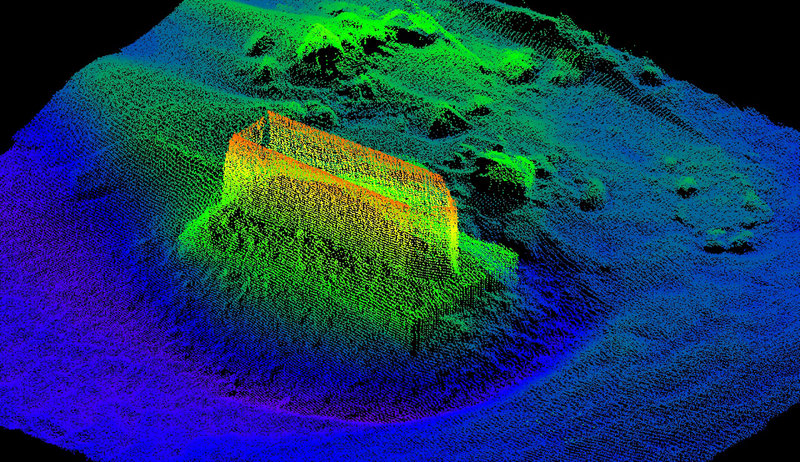

Such accuracy is important for creating baseline data. In the years ahead, the Department of Transportation can compare the bathymetry — water depths — from early surveys. Signs of increased scour around bridge supports will be easier to spot. If it looks like trouble, Edwards and his divers can repair damaged piers or fill scour holes.

It will take weeks of work with data processing and imaging software for Reis and Waddington to refine the baseline information collected in Wiscasset and present it to the Department of Transportation.

Images created last year at the Kennebec River bridge clearly show the bathymetry, with a purple shade indicating deep water upriver from a pier and its foundation. Reis and Waddington were back at the Kennebec River bridge last week, doing a second survey.

The bridge’s piers are set on ledge, Edwards said, so he’s not concerned about the present condition. The follow-up images that are being prepared will measure any changes in the water depth.

“It’s out of sight, out of mind,” Edwards said. “There might not be anything wrong with a bridge, except scouring.”

Staff Writer Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at: tturkel@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.