The concept of the Big Year has a long history in birding. During a Big Year, a birder seeks to identify as many birds as possible in an area of interest. That area might be a county, a favorite patch of birding habitat, a state or even a continent.

The first well publicized Big Year was done by Roger Tory Peterson and his British colleague, James Fisher in 1953. Peterson wanted to show his friend the diversity of the North American avifauna. Over 100 days, the two traversed the continent from Newfoundland down the East Coast to Florida, and from Texas and the desert Southwest up along the Pacific coast to Alaska. Fisher and Peterson wrote “Wild America,” an engaging account of their trip.

Scott Weidensaul repeated Peterson’s and Fisher’s trip on its 50th anniversary. “Return to Wild America” chronicles the changes in our bird fauna since the “Wild America” trip.

A notable North American Big Year was Kenn Kaufmann’s effort in 1973, when he managed to find 666 species. Kaufmann did his trip on the cheap, thumbing his way back and forth across the continent. “Kingbird Highway” is his account of that Big Year.

One other notable Big Year book is Mark Obmascik’s “The Big Year,” in which he describes North American Big Year efforts in 1998 by three birders, one of whom found an eye-popping 745 species.

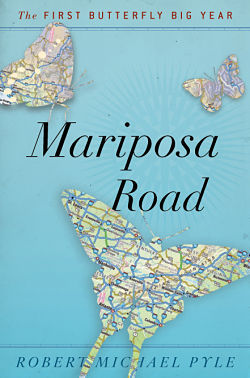

Just last month, a book describing a different kind of Big Year hit bookstore shelves. Robert Pyle did a North American Big Year in 2008 for butterflies. “Mariposa Road” is the lively and charming account of his adventures. Mariposa, by the way, is Spanish for butterfly.

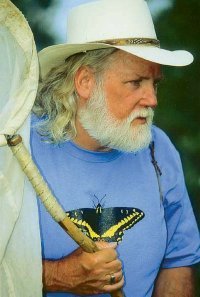

Pyle is an accomplished nature writer. His 14 books include “Wintergreen,” the winner of the 1987 John Burroughs Medal for Distinguished Nature Writing. He has been studying butterflies since his childhood in Colorado. He has a doctorate from the Yale School of Forestry, where he studied under Charles Remington, one of the foremost butterfly biologists of the 20th century.

Pyle has had a varied career (the Nature Conservancy, visiting faculty member at a number of colleges, scientific consultant and museum curator), but the two themes that span his career are butterfly conservation and nature writing.

In 1971, Pyle established the Xerces Society, a conservation organization devoted to invertebrates. The organization is named after a butterfly, the Xerces blue, a now extinct butterfly that used to live on dunes near San Francisco. Urban development caused the extinction of this species.

Inspired by the birding Big Years of Peterson and Kaufmann, Pyle decided a grand tour of North America to gauge our butterfly populations was in order. His Big Year resulted in $45,000 for the Xerces Society through a Butterfly-a-thon in which donors pledged money for every species seen.

Pyle and his wife live modestly in Washington state, so expenses had to be carefully monitored. Most of the driving was in Pyle’s Honda Civic named Powdermilk (over 350,000 miles on the odometer) and plane tickets came from speaking engagements around the country. In all, he plunked down about $16,000 for his yearlong adventure.

His Big Year carried him on several cross-country junkets, including Alaska and Hawaii (seeing 15 of the 18 species that occur there).

Of the roughly 800 species in North America, he saw 478 species. He was hoping to crack 500 but his wife’s unexpected health problems forced him to abandon some of his trips (he regretted not visiting Vermont or Nova Scotia).

He briefly visited Maine, getting to see the Clayton’s copper near Winn.

Even if you don’t know a hairstreak from an elfin, reading this book can give great joy.

There is the exhilaration of seeing a rare butterfly or particularly beautiful common ones, with the disappointment of missing hoped for species. Fickle weather plays a big role in butterfly hunting; butterflies are not active during inclement weather.

Pyle notes the birds, snakes and other wildlife he sees, too.

He is a gregarious person, and introduces us to many butterfliers around the continent. Pyle is quite a character himself. His tendency to be late and his forgetfulness make for a number of riveting anecdotes.

As an example, he left a yogurt container of some of his specimens at a restaurant and had to go dumpster diving days later to search for them.

I admire his graceful writing style, filled with clever allusions and puns.

I grinned when he wrote about an expedition to find Behr’s sulphur. Checking his equipment, he was loaded for Behr’s.

Herb Wilson teaches ornithology and other biology courses at Colby College. He welcomes reader comments and questions at:

whwilson@colby.edu

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.