Is LNG dead in Maine?

The answer is likely to come in the next year or two.

Since 2003, a succession of proposals to build a terminal along the Maine coast to import liquefied natural gas have failed. The most recent, Calais LNG, withdrew its permit application with state environmental regulators last week. Unable to find new money after a primary investor pulled out, the developer blamed lingering impacts from the global financial meltdown.

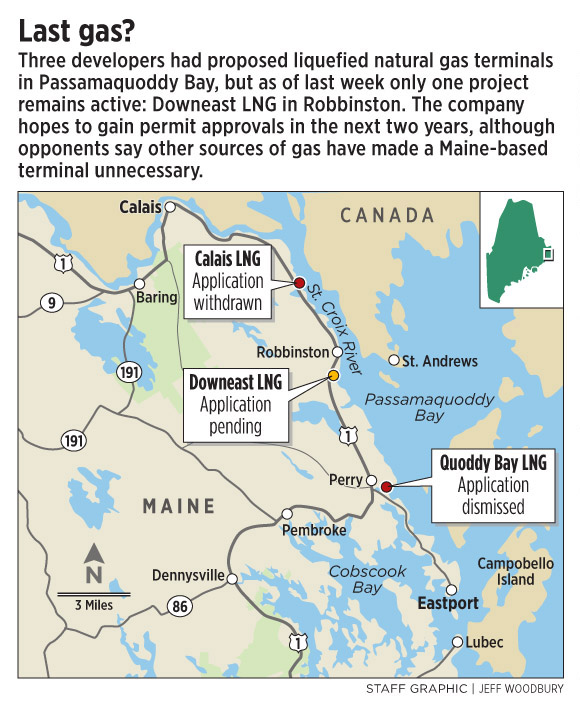

Calais LNG was one of three terminals planned for the St. Croix River and Passamaquoddy Bay, on the Maine-New Brunswick border. Following its demise, and with the failure of an earlier competitor, Quoddy Bay LNG, a single project now represents the final hope for bringing a new source of natural gas directly to eastern Maine.

“We always believed we’d be the last man standing,” said Dean Girdis, co-founder and president of Downeast LNG.

Downeast LNG has a site in Robbinston, downriver from Calais. It’s slowly moving through the regulatory process and hopes to gain federal permits next year, and state permits in 2012. The project’s private investors, who Girdis says have spent $17.5 million so far, continue to see unmet, future demand for natural gas in New England that can be satisfied by LNG.

Diverse interests — including outgoing Gov. John Baldacci, the state chamber of commerce and organized labor — have rallied behind the terminal proposals. They say LNG is critically important for creating jobs, displacing oil and providing cleaner, less-costly energy for the state’s industries.

But advocacy groups and residents in both the U.S. and Canada who are worried about the effects of LNG on tourism, fishing, navigation and the environment disagree. They say Downeast LNG is doomed by the same forces that hobbled Calais LNG: a new glut of natural gas that has reduced the need for imported LNG and has scared away investors.

“LNG terminals in Passamaquoddy Bay just don’t have a future,” said Sean Mahoney, vice president of the Conservation Law Foundation in Maine.

Newly discovered shale gas deposits in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast states will boost the region’s supply, Mahoney’s group asserts. Aided by the recently-opened Canaport LNG terminal in New Brunswick and two small, floating terminals off Massachusetts that can feed pipelines in Greater Boston, New England will have an adequate supply for many years, the group says.

But Girdis and other LNG advocates say critics are overlooking a key detail. Two major pipelines through southern New England that can carry gas from the shale basins — the Tennessee Pipeline and the Algonquin Pipeline — already are at capacity in the winter and have no room, and no political support, to expand. A consultant’s report done last month for Downeast LNG highlighted this conclusion, adding that New England already gets a large share of gas shipped from Europe.

“Markets in the Northeast will be among the last in the U.S. to receive shale gas on a consistent, year-around basis because, for shale gas, the Northeast is still the end of the line, while, for LNG, the Northeast is closer to the middle of the stream,” it said.

This is an important distinction, according to Tony Buxton, a Portland lawyer who represents industrial interests in Maine and had worked for Calais LNG. Maine pays a premium for natural gas, Buxton said, partly because of Canaport’s ability to influence prices. The wholesale cost of gas also affects the price of electricity, which fuels many of the region’s power plants.

If Maine had an LNG terminal with storage tanks and a firm, year-round delivery schedule, Buxton said, that could make it profitable for developers to build lateral lines to eastern Maine mills that now burn hundreds of thousands of gallons of oil every year.

“No one will build a pipeline unless there’s a firm, year-round supply,” he said.

Nationally, though, the outlook for new LNG import terminals is bleak.

Nine U.S. terminals operate today, including the nation’s oldest, in Everett, Mass. More than a dozen have won federal permits, part of a wave of projects planned to meet an expected gas shortage that evaporated during the recession. Only a few are moving ahead now and a couple of them, in Texas, are instead being fitted to ship domestic gas overseas.

But Maine and New England are in a different situation, according to Bill Cooper, president of the Center for LNG, an industry trade group. LNG terminals are designed to operate for roughly 40 years, over many cycles of market conditions. The Everett, Mass., terminal is at capacity and the region’s only new facility with storage is in Canada.

“Do you want to base the next 40 years on one new terminal?” Cooper asked. “You can’t make long-term energy decisions based on (today’s) market.”

At Downeast LNG, Girdis is taking that long view. He has been working full-time on the project since 2004. Under the most optimistic timeline, it wouldn’t be operating until 2016.

A Boston native who spent summers as a child in the Old Orchard Beach area, Girdis has worked in the LNG sector around the world. Now based in Washington, D.C., he studied 30 possible LNG sites from Connecticut through Maine. Passamaquoddy Bay, with its protected harbors and deep water, ranked highest.

Downeast LNG’s prime financial backer is Kestrel Energy Partners, a New York private equity investment firm led by Paul Vermylen, whose background is in the oil and financial industries. Girdis said Kestrel plans to spend $19 million to secure federal and state permits.

Downeast LNG has also drawn interest from an international company that wants to build and operate the terminal, Girdis said, as well as a gas supplier. But nothing can move ahead without permits.

Downeast LNG’s attempt to gain a federal environmental permit has been delayed by requests for additional information. That’s pushing the process — and a decision by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission — into early next year. If successful, Downeast LNG will need to resubmit permit applications to the state.

Project opponents are hopeful that the obstacles that brought down Calais LNG and Quoddy Bay LNG also will trip up Downeast LNG.

Ronald Shems, a lawyer for Save Passamaquoddy Bay, said the experience of the bay’s other two LNG proposals suggests that energy projects aimed for the wrong locations die for reasons other than pure opposition. “We may not have to put the nail in the coffin,” Shems said. “The market, FERC and state regulators may do it for us.”

Staff Writer Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at:

tturkel@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.