The English ensemble drama “Another Year” stars Jim Broadbent as a civil engineer who takes geological core samples of the world we stand upon and determines how much stress it can bear. In a way, that’s what Mike Leigh’s film does.

Leigh digs deep into the lives of his characters and tests their resilience as they face the slings and arrows of late middle age. Some drink away their worries, others joke, a few assume stiff upper lips, and a couple stare into the future as if facing a firing squad. It’s a core sample of human experience in an average, regular year from spring through winter, with life and death and hope and disappointment layered atop one another.

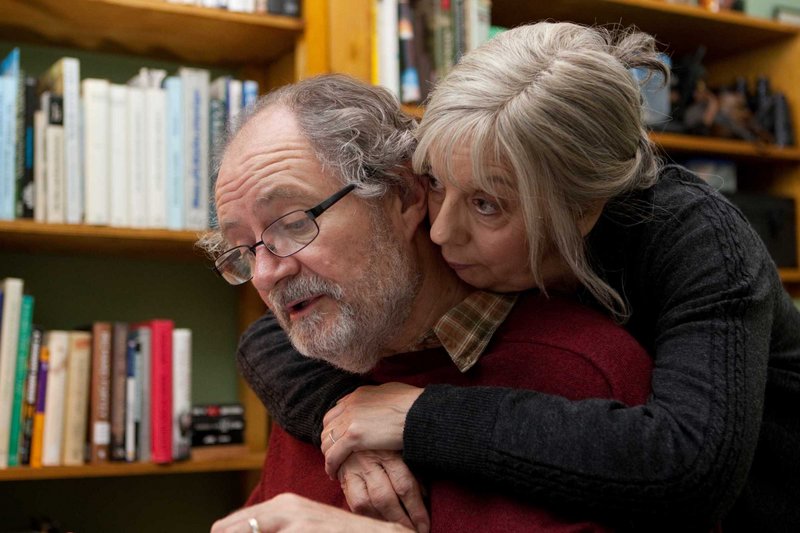

There are several varieties of midlife crisis on display here, all the more captivating because of the characters’ can’t-complain, carry-on attitude. Broadbent’s Tom is one of the lucky ones blessed with a compatible, loving partner in Gerri (Ruth Sheen, who possesses the world’s most winsome overbite). They have weathered life’s traumas through consistency (they tend tomato plants and throw regular garden barbecues), compassion (Gerri is a medical clinic therapist) and holding tight to their values.

Tom, who has kept his old Che Guevara posters, concedes that such liberal gestures as recycling don’t have much impact, but one does it anyway. “Must set a good example,” he says. He’s a good man but a trace too smug and judgmental, more a gracious host than an openhearted friend. You can practically smell the sandalwood incense when the old bohemian comes onscreen.

The contented couple are the stable center of a solar system of co-workers, pals and relatives who pass near and recede as the seasons turn. You are never quite sure who will turn out to be an important character in the flow of Leigh’s naturalistic films. A character might enter seeming significant and disappear or drift in and surprisingly take center stage.

Gerri’s chipper, birdlike secretary, Mary (Lesley Manville, in a performance so three-dimensional it reaches into the auditorium), flirts incessantly, overestimating her dimming sex appeal and clinging to youth with a colorful wardrobe and a dilapidated red subcompact. Despair flits around the edge of her crow’s feet, and when she visits friends for dinner and consolation, her evening out often turns into an inebriated sleepover.

Then there’s Tom’s old college mate Ken (Peter Wright), the sort of man who wouldn’t consider eating on an empty stomach. Hoovering up food at an alarming rate, he’s trying to fill an emotional hole with chips and ale.

“Life’s not always kind, is it?” clucks Gerri. That point is driven home dramatically in the prologue scene of an unrelated character’s medical interview. Imelda Staunton is searing as Janet, an embittered woman visiting Gerri’s clinic for sleeping pills. Gerri asks how happy she feels on a scale of 10. “One,” Janet snaps. “What would improve your life?” Gerri presses. “A different life,” she retorts.

Leigh, a director who creates his stories through long periods of rehearsal and improvisation with his cast, specializes in indirect, understated, nonverbal expressions of emotion. Here, as always, he is perceptive about the ways people come close to saying what they mean but never quite come out with it. Janet’s pessimism sets a rare note of candor. Leigh’s characters often try to fool themselves, as Mary the functioning alcoholic does when she insists “No, I’m really comfortable with where I am in my life.”

The lucky ones here are Tom, Gerri and their grown son Joe (Oliver Maltman), who finds a sweet, funny girlfriend in Katie (Karina Fernandez) when they’re both stood up. They can laugh off life’s embarrassments. Mary, who reacts to the new girl in Joe’s life with needy, possessive jealousy, sabotages the only friendship in her life offering solid emotional support. Her old friends, who accepted her zany ways without reproach, withdraw, setting up the story’s fourth-act crisis.

As winter approaches and the film’s visual palette shifts from floral warmth to overcast chill, every character has cause to consider how they negotiated the year’s turning points. The fade-out, constructed around a sustained moment of silence and a slow zoom in on a single character’s face, proves that quiet, understated moments can have more power than a barrel of special effects.

“Another Year” is one of the finest dramas in ages.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.