SPRINGFIELD, Ill. – After two decades of debate about the risk of executing an innocent person, Illinois abolished the death penalty Wednesday, a decision that was certain to fuel renewed calls for other states to do the same.

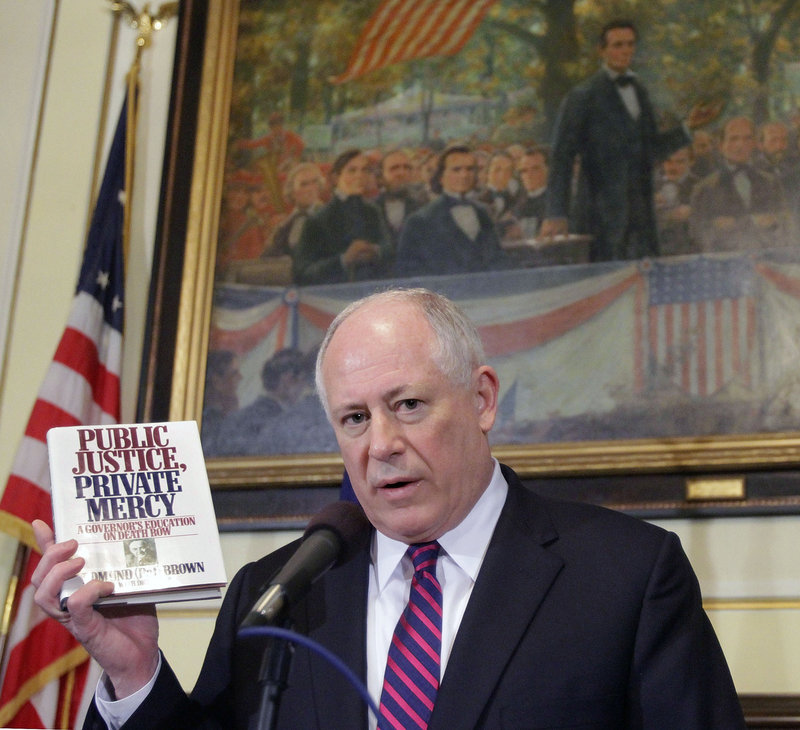

Gov. Pat Quinn, a Democrat who has long supported capital punishment, looked drained moments after signing the historic legislation. Lawmakers sent him the measure back in January, but Quinn went through two months of intense personal deliberation before acting. He called it the most difficult decision he has made as governor.

“If the system can’t be guaranteed, 100-percent error-free, then we shouldn’t have the system,” Quinn said. “It cannot stand.”

Illinois becomes the 16th state in the nation without a death penalty more than a decade after former Gov. George Ryan imposed a moratorium on executions out of fear that the justice system could make a deadly mistake.

Quinn also commuted the sentences of all 15 men remaining on death row. They will now serve life in prison with no hope of parole.

In his comments, the governor returned often to the fact that 20 people sent to death row had seen their cases overturned after evidence surfaced that they were innocent or had been convicted improperly.

Death penalty opponents hailed Illinois’ decision and predicted it would influence other states.

“This is a domino in one sense, but it’s a significant one,” said Mike Farrell, the former “MASH” star who is now president of Death Penalty Focus in California.

The executive director of a national group that studies capital punishment said Illinois’ move carries more weight than states that halted executions but had not used the death penalty in many years.

“Illinois stands out because it was a state that used it, reconsidered it and now rejected it,” said Richard Dieter of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington.

New Jersey eliminated its death penalty in 2007. New Mexico followed in 2009, although new Republican Gov. Susana Martinez wants to reinstate the death penalty.

In New York, a court declared the state’s law unconstitutional in 2004.

The U.S. is one of the few industrialized countries that still practices capital punishment. The European Union, for instance, bans executions by any member nations.

Quinn’s decision incensed many prosecutors and relatives of crime victims. Robert Berlin, the state’s attorney in DuPage County, west of Chicago, called it a “victory for murderers.”

The governor reflected on the issue week after week, speaking with prosecutors, crime victims’ families, death penalty opponents and religious leaders. He consulted retired Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa and met with Sister Helen Prejean, the inspiration for the movie “Dead Man Walking.

Quinn “realized that it’s a righteous and a moral decision to end this system that almost took my life,” said Gordon “Randy” Steidl, who spent 12 years on death row after being wrongly convicted in the 1986 murder of two newlyweds.

In the future, “there won’t be any more Randy Steidls that are standing in a court of law that are innocent and facing a sentence of death. At least they’ll be alive to prove their innocence on down the road.”

A Chicago woman whose teenage son was gunned down in 2006 said the killer, who has never been caught, should not be allowed to breathe the same air she breathes.

“I am a Christian. I never believed in killing nobody else,” Pam Bosley said, explaining her change of heart after her son was shot outside a church. “But the pain you suffer every single day, I say take them out.”

Quinn said capital punishment was too arbitrary.

A prosecutor in one county might seek the death penalty, while another prosecutor dealing with a similar crime might not, he said. And death sentences might be imposed on minorities and poor people more often than on wealthy, white defendants.

A Gallup poll in October found that 64 percent of Americans favored the death penalty for someone convicted of murder, while 30 percent opposed it. The poll’s margin of error was plus or minus 3 percentage points.

The high point of death penalty support, according to Gallup, was in 1994, when 80 percent were in favor.

Doubts about Illinois’ death penalty grew steadily throughout the 1990s with each revelation of a person wrongly sentenced to die.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.