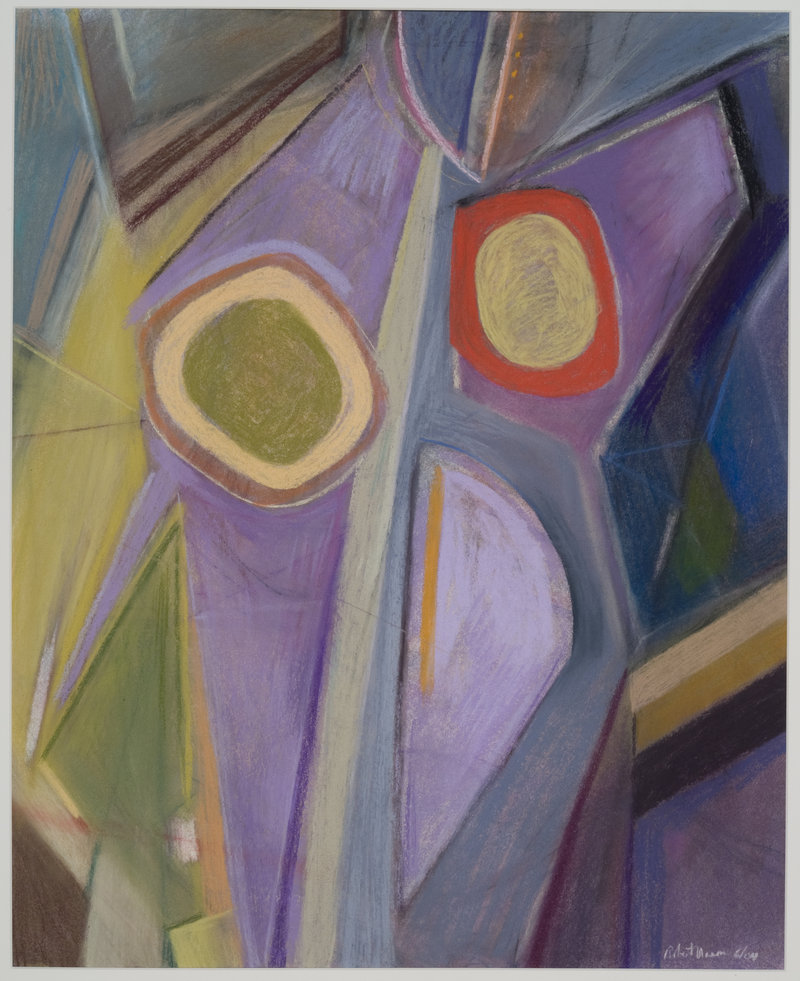

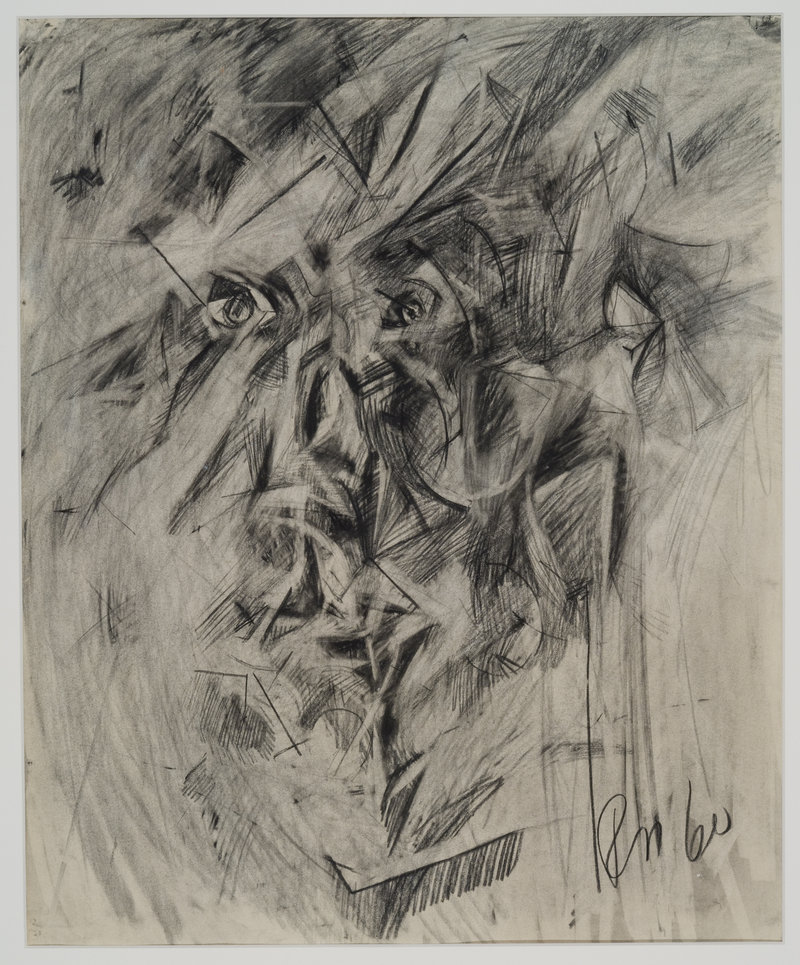

“Journeys to the Interior” at Addison Woolley Gallery is a rare pleasure. It brings forth the work of a reticent, at least in local terms, intellectual and beautifully accomplished painter.

The artist is Robert Nason, and the show is touched by a sense of discovery. Here, on Washington Avenue, are paintings by a formidable artist, schooled in history, with an oeuvre that transcends synthesis. And he seems to have simply materialized for the event.

For viewers, the show is one of those unexpected rewards that go with the years of viewing. We are an inbred, mutually supportive community of remarkable strength — but perennially lacking in freshness.

“Journeys” provides the missing quality. Its attitudes are fresh to Maine, but not to art history or indeed to the artist himself. On quick review, the work is grouped into two periods, the ’60s and the late ’90s.

It would be convenient to say that the early group reflects the School of Paris and the later makes reference to what has taken place in this country more recently, but it doesn’t read that way. The latest paintings can embrace erstwhile surreal elements or the fractured dispersions of early Cubism, while both periods reach out to tightly considered forms of geometric abstraction.

My point is that this is beautiful work evoking the pleasures of history, but not a synthesis of it. It is more than a matter of borrowing forms for aesthetic convenience; rather, it’s a matter of pursuing a consistently independent vision within the context of great achievements of the past. There is a world of difference between the two. The willingness to intelligently embrace history gives these beautiful paintings an evocative quality that is wholly distinct from their substantive achievements.

THE EDGE OF EXTINCTION

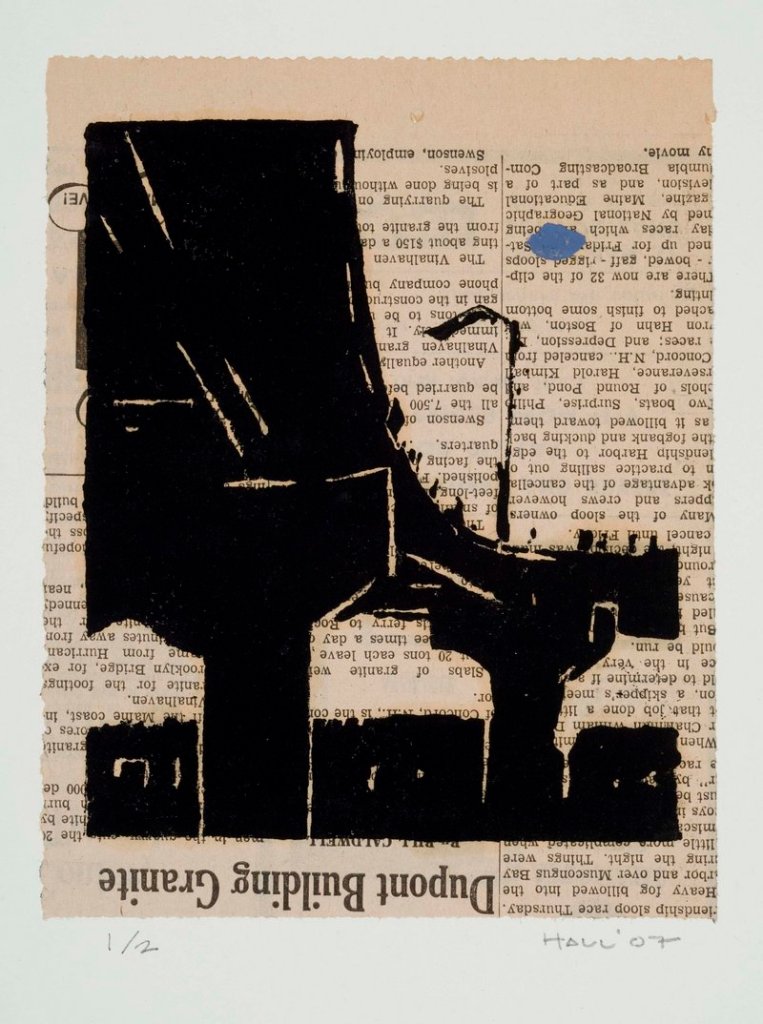

I have confessed to a predisposition toward Tom Hall’s prints. I know Hall’s work; there is a solid consistency to it that I find reassuring and, all in all, it is irresistible to me.

Hall sometimes prints on newsprint or on old grocery bags. The work is generally in black-and-white monotype, and its appearance on such casual materials is touchingly fugitive. There is ephemerality to monotype, and both newsprint and bags are born to expire. It may all disappear one day.

In Hall’s exhibit at the June Fitzpatrick Gallery, they have a commonality with the earliest forms of collage — made of newsprint, cardboard and other disposable stuff, they too lived on the edge of extinction.

This quality, with the impenetrable blackness of Hall’s images, sets up a tension that I can almost touch. The images are intent on extracting the life force from the coarse underlying paper which, in turn, hastens their own demise.

The images are generally of dark woodlands, and they can be seen on Saturdays in March and always by appointment at the gallery.

STRONG SCULPTURES

I now suggest that you direct your stalking to “A Conference of Birds II” at Gleason Fine Art. The exhibit is gathered from among gallery residents and a few irregular migrants. There are 16 attendees in all; all conform to the gallery’s adherence to highly accomplished, representational work.

There are some beautiful images and strong sculpture in this show. I’ll start with a note about the sculpture. Representational sculpture hasn’t gotten much attention for decades. Sometimes demoted to be garden pieces, they lose their finesse among the flowers and their status among the arts.

Even pieces intended for indoor presentation are often sited for their decorative value and lose out to more easily approached paintings. This is a pity, because there are carvers among us who produce wonderfully intense work, and workers in wrought iron that so dematerialize mass that it acquires the vitality characteristic of drawing.

In this show, I note the work of Patrick Plourde in metal, the carvings of Cabot Lyford and Don Justin Meserve, and the fantasies in wood by Donna Dalton. (As a group, they’re called “Wheeled Wooden Birds,” and if you’ve never seen a flycatcher riding on a dragonfly, Dalton’s carvings offer a new slant on natural history.) I also note the upward litheness work in bronze by Andreas von Huene. His creatures poke in swamps, but are fully able to rise.

Dalton’s carvings suggest folk art, and that leads me to the work of Jeff Barrett, which comes close to the tramp art of the 1930s. His largest piece in this show is a comprehensive account of a lobster bake in high wood relief fully outfitted with the requisite gull and a distant lighthouse. It’s a full-color achievement in kitsch, and looks terrific.

Genetta McLean’s “Mantegna’s Screen” is a major painting by an artist who brings Renaissance technique and a Renaissance sensibility to her work. I can’t identify the two fetching black-and-white birds that sat for their portrait, but I’m guessing they’re magpies.

Scott Kelley is an established painter of birds, and pre-eminent among those so engaged in these parts. His work can be lyrical and, when of eiders against a flat, colorless background, verges on the surreal. Two works by him in this show — a double-crested cormorant and an osprey — are major efforts, powerful and sinister, but the illogical eiders carry the day.

I also note “Based on a True Story” — a colored block print of a cormorant caught in a lobster trap by Kim and Philippe Villard — and a group of four patterned prints of black birds and cormorants by Gayle Frass and Duncan Slade.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 45 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.