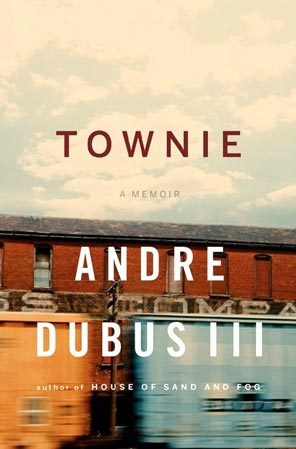

With 1999’s “The House of Sand and Fog,” which was an Oprah Winfrey-blessed best-seller and National Book Award finalist, novelist Andre Dubus III (pronounced dub-YOOSE) finally escaped the shadow of his father, acclaimed short-story writer Andre Dubus II.

Until “Sand and Fog,” the younger Andre was forever explaining to journalists and others that he wasn’t that Andre Dubus.

He followed that novel with 2008’s wrenching “The Garden of Last Days,” the best fictionalized look at the events leading up to 9/11 that I’ve read.

Now Dubus turns his focus inward with the memoir “Townie,” an enormously affecting, often disturbing look at his youth in a series of depressed Massachusetts mill towns along the Merrimack River. Dubus has an eye for searing detail that is unequaled so far this century, at least in my reading, and he employs that here to maximum effect.

It’s hard to believe that the same keenly articulate man who wrote the elegant prose of “Sand and Fog” and “Garden” is the same Andre Dubus described in these pages: a skinny kid who learned to fight as a way to protect himself and those he loved. (He had good reason to believe they needed him; during the course of his teen years, his younger brother Jeb tried to kill himself, and his older sister Suzanne was gang-raped.)

He grows stronger and it slowly dawns on him that some of his enemies are actually afraid of him; he calls the emotion this invokes “earned and glorious and edged with blood.” Soon teenage Andre craves the crunch of fist against bone with as much fervor as his contemporaries covet drugs and alcohol.

During the same period when he was brawling in the riverfront alleyways, though, Dubus was surrounded by his parents’ artsy, literary friends, and their sensibilities seeped into him as if by osmosis. Dubus describes living next door to the Vonneguts: “The father, Kurt, would walk down to our house every afternoon and sit with us four kids in the living room and watch Batman on the small black-and-white.”

“Townie” serves as a sort of singed valentine to the elder Dubus (he died in 1999), who’s depicted as a complex, loving man who couldn’t fully commit to anything but his literary work. Although it’s ultimately a loving representation of his father, the younger Dubus doesn’t flinch when describing his frequent frustration with, and even rage at, his dad. When he phones to tell his dad that Suzanne has been raped, he feels “this dark joy spreading through my chest at having just done that to him, the one who should have been here all along, the one who should never have left us in the first place.”

Dubus’ backward vision of his mother, Patricia, is more universally flattering, especially with regard to her mettle while facing single motherhood and poverty. “I don’t believe she ever filled a (gas) tank,” Dubus recalls. “So many times she’d pull up to the pumps, dig through her purse for change, smile at the attendant, and say something like, ‘A dollar and fourteen cents’ worth, please.’ “

The first hint of Dubus’ future as a writer comes about 100 pages in, when, sitting in the back of a paddy wagon after a street melee, he talks the other guy into feeling sorry for him.

” ‘Cancer,’ he tells his tormenter. ‘It’s in my bones. … I just came here to have some fun, that’s all.’… I looked back at him, and it was like looking into the face of a small boy, his eyes on me but also on himself, on his own, hopefully distant, mortality.”

Ah. The power of storytelling.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.