“The Hidden Presence of Places” is a respectful bow to a pre-eminent American artist, photographer Paul Caponigro. A large and beautifully composed effort by the Farnsworth, the show traces the work of a man whose presence in photography increases as the weight of that form diminishes.

As classic photography – a system of producing images through the manipulation of optics, light-sensitized material and chemistry – continues its ineluctable decline, a master such as Caponigro moves further into the realm of the giants.

This grand event portrays the benefits conferred on him by a lineage leading through Edward Weston and Minor White and his assumption of the burdens that accompany them. To create empathetic images that are wholly dependent on the tuning of the eye and in the ultimate mastery of classic techniques is his continuing obligation to history and to the art form itself.

That Caponigro has acquitted himself brilliantly on both counts is a long-established fact. This splendid exhibition reminds us of that achievement.

Inevitably, however, the event is touched by nostalgia – not for Caponigro, who continues to make pictures with depth and gravity, but for the art as we have received it. It reminds us that the photography that we have known has been deprived of much of what succeeding generations would have added to it. Technologic cleverness is a poor trade for the brand of integrity assumed by Caponigro.

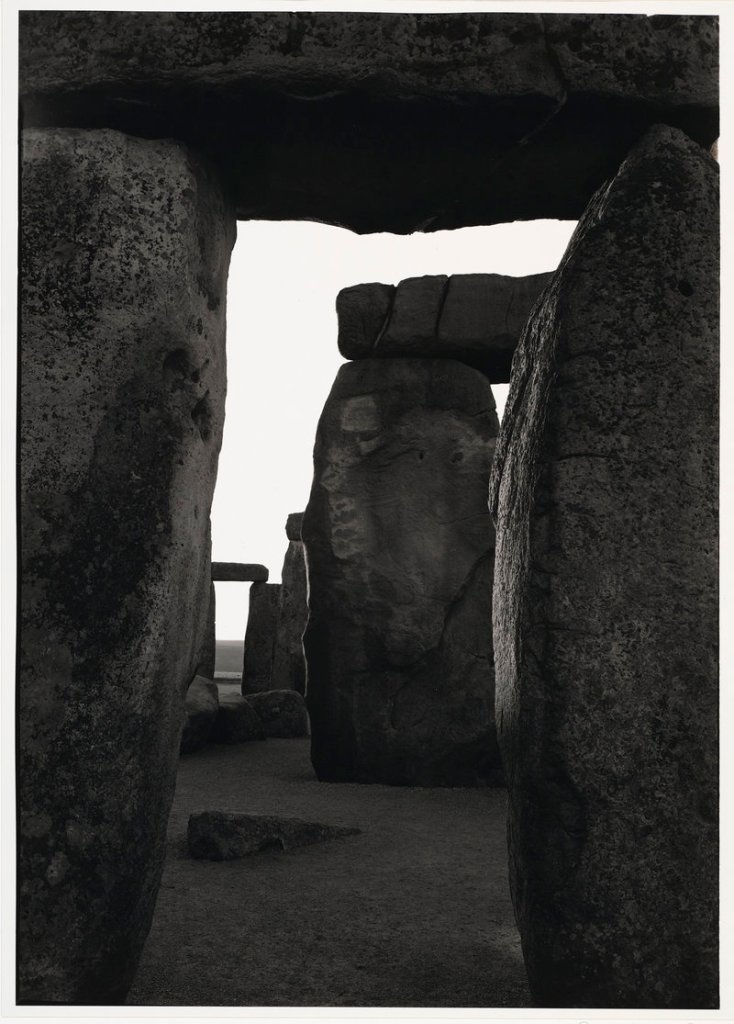

The exhibition is presented in a sequence of sections coincident with the sequence of his career. It carries the viewer through the intuitions in his early images of the natural world made in Massachusetts (he was born in Boston and has lived in Cushing for several decades), his adjustment from the East to the West Coast, his travels with Minor White in the West and their excursions into Zen, his return to the East and Boston, his intervals in Ireland in the 1960s, in Japan in the 1970s, among the megaliths of Collanish in the Hebrides in 1972, his work at Stonehenge in that year and in the years 1967 and 1970, his images in France in 1987, and a great deal more.

Some of his works that fit into these venues and have since achieved iconic status are absent from this exhibition. I have in mind the running deer of County Wicklow made in 1967, the image of the root-encumbered tree at Avebury of the same year, and most of the wonder-infused images of Stonehenge.

I assume that the absences were intended to give focus to lesser-seen examples of his work, particularly those that exemplify a seeking of silence. As a whole, the exhibition can be thought of as stations in such a search.

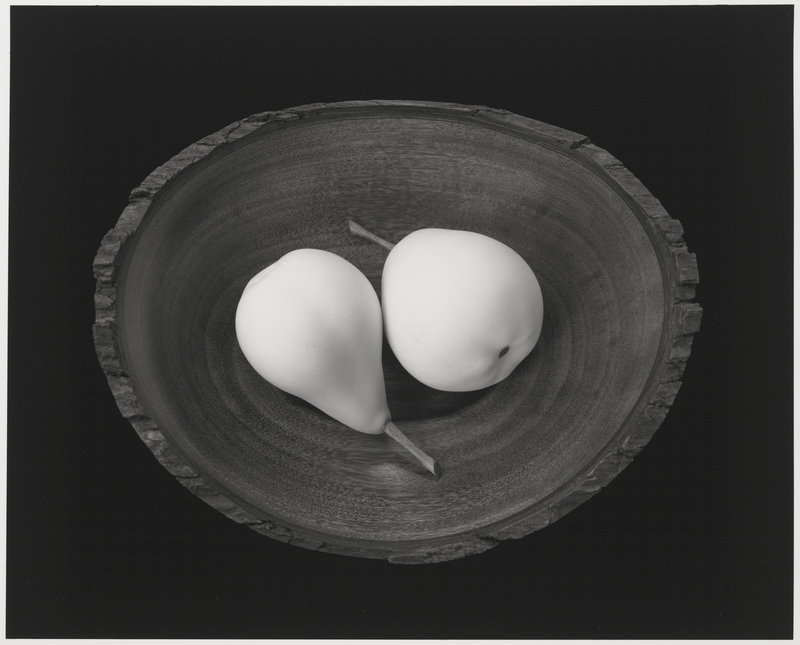

This is easily seen in immaculate still lifes such as “Two Pears” (1999) and “Abalone on Paper” (2009), and as easily in his work on the ancient Celtic churches of Ireland. They sit in unyielding severity, staunch, silent, judgmental. Here, I have in mind the magnificent “Clonfert, Romanesque Door” (1967).

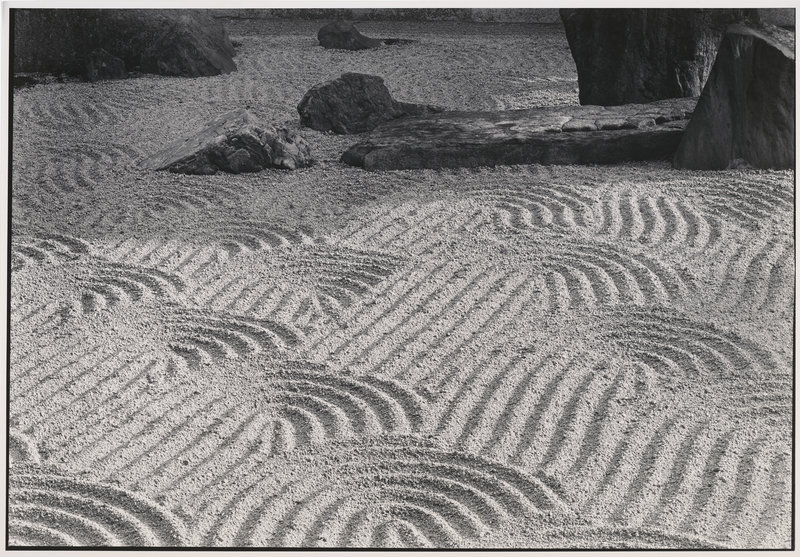

The silence in his temples at Kyoto is more gentle and internal. It considers the floor at Tofukuji, so worn down by shoeless feet that its knots form a private topography, and the heart-touching Hiei-San Temple, almost formless in the early mist. Neither appear to have ever spoken. Perhaps they were built in silence.

This is a magnificent tribute to an artist who, for every good reason, has been given the museum’s 2011 Maine in America Award. His contributions to the art of photography can sometimes, in the words of Kenneth Clark, appear to be the divine agitation of the creative artist.

ROBERT HAMILTON’S PRIMAL COLORS

The agitation in the work of the late Robert Hamilton (1916-2004) is of a different stripe. In its exhibition “The Last Paintings,” the Center for Maine Contemporary Art offers Hamilton’s final and most dream-laden work.

Although I think of myself as familiar with his paintings, I was unprepared for the richness of this exhibition. I use that term in connection with the work itself, for while the show is quite small, the painter offers us references to his fantasies with such generosity that they warm the cockles of your heart.

Much of this is drenched in out-of-the-can primal color. Hamilton’s colors set the universe of his dreams ablaze. The contrast between their ferocity and the painter’s account of romantic voyages, imagined but never taken, give his paintings eternal buoyancy. His dreams will ever float on their energies.

The work at CMCA is not a complete account of Hamilton, but it does hint at the essential character of his art. Hamilton sustained his work on the boundaries – the edges – of the unconscious. His dreams, the scramblings of his memory, his fantasies about other places and the slow urgency to reach them combine to convince us that a world of the imagination exists. I somehow think that he believed that it did.

There is too much in this show and in his work in general that is concerned with travel for there to be no destination. Under these circumstances, imagination itself can be the destination. To journey to a realm created by one’s own vision justifies the cost of the ticket. Hamilton took repeated trips to that realm.

In doing so he rowed up the Nile, was a passenger in spooky railroad carriages, hitched rides with the circus and often belted along in his old World War II P-47 Thunderbolt. The plane did not have the rapid grace of a British Spitfire, but what’s the hurry? The realm of dreams is perennial; it will wait until you get there.

If you have a taste for history and other enchanted worlds, think Henri Rousseau and his “The Dream” idyll. The nude in it floats just as does Hamilton’s plane in his own arms in “Same Old Dream.” Time in each is suspended on the edge of the unconscious.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 46 years. He can be contacted at: pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.