It was the summer of 1976 when Heidi Coleman was playing on her family’s farm in Maine, her little toy boat in hand. Somehow the 3-year-old wandered into a pond on the property, where she accidentally drowned.

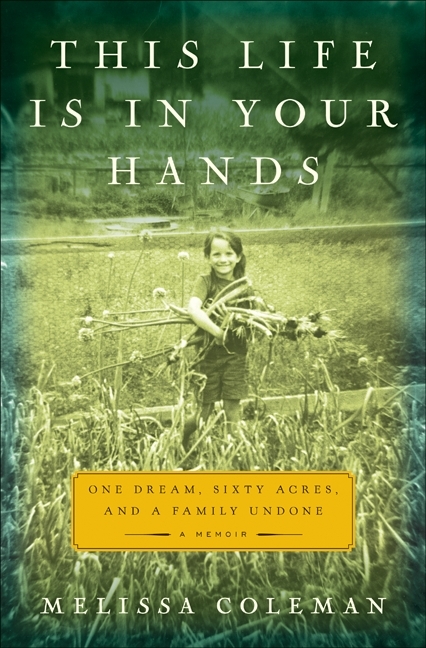

That incident is the puzzle at the core of a haunting new memoir, “This Life Is In Your Hands.” Author Melissa Coleman, who was 7 when her younger sister died, tells the story from dual viewpoints — as a child navigating the bumpy terrain of sibling ties, and as an adult, now in her 40s, looking back at a radically different and simpler time.

The story takes place in the era of Nixon and Watergate, hippies and homesteading. Eliot and Sue Coleman were a handsome, adventurous young couple who had read the homesteader’s bible, “Living the Good Life.”

Drawn to its pioneering values, they sought out its authors, Helen and Scott Nearing in Harborside, Maine, trailblazers in America’s back-to-the-land movement.

In time, Eliot and Sue would become the Nearings’ proteges and neighbors. They bought 60 acres from the Nearings and began living off the grid. Eliot built a 400-square-foot home, cleared the land and planted crops. Greenwood Farm was born.

The farm was an idyllic setting for young children. The author and her little sister, Heidi, could romp and hide in the woods and gardens, their naked bodies natural as the landscape.

In warm weather, the farm resembled a nudist commune, people going about their work in the buff. Then someone would shout, “pants dance!” signaling the arrival of visitors at the farmstand, and everyone clambered to get dressed.

Over time, Greenwood Farm built a reputation for its growing methods and vibrant produce. Eliot was learning about biological agriculture and would later become, through his books and teaching, a major force in the world of organic gardening.

A reporter from The Wall Street Journal came out to interview him and see how the hippie venture operated. One newspaper article begat many others, which brought welcome business to the farm.

Equally welcome were inquiries from students and visitors. People wrote to Eliot, wanting to apprentice at the farm. As the apprentice program grew, it took on a life of its own, requiring a campground to house the rotating influx of trainees.

But while the farm was becoming a bustling and expansive place, the Coleman household was crumbling, a model of dysfunction.

“When Mama ‘checked out’ to cope with her emotions,” Coleman writes, “Heidi and I ran from the house, screen slamming, to find engagement in the life of the farm and intrigues of summer.”

Their mother would often “need some space” or go into “hibernation mode,” as she would tell her girls. Yet a remote, depressive mother was only part of the problem.

In his way, Eliot, too, was an absentee parent. As he began spreading the gospel of organic gardening through mentoring and travel to farms abroad, his focus veered further from the family, compounding his tendency to overwork.

“The more people came to our farm, the more competition I had for (Papa’s) attention,” Coleman says. Then, later: “When Heidi drowned, my heart grew a hidden thought. ‘Maybe now I’ll get the attention I need,’ it whispered. ‘Maybe now our family will be happy again.’ But it didn’t work out like that at all.”

Coleman’s was a lonely childhood marked by her parents’ separations and assorted other lapses.

On visiting her grandmother’s house, for instance, she feared setting the dinner table improperly, as she was familiar only with wooden bowls and spoons. Sometimes she would forget to wear underwear to school — “no one cared about those things at home,” she recalls.

And she was grateful when Frank, one of the apprentices, spanked her for misbehaving. “While I was mad at Frank for a long time after that,” Coleman says, ” I also felt a reverence of sorts. He’d drawn a line, the boundary I so badly needed and I loved him for it.”

Although Coleman cites ample evidence of dubious parenting throughout the book, she casts no blame for Heidi’s death. Nor does she indict the cultural mores of the time that enabled their free-range childhood. It’s safe to say, however, that her parents’ eventual divorce and departure from the farm were hastened by the irreparable course of events.

Coleman’s memoir is, at once, a period piece evoking the counter-culture of the ’60s and ’70s, and a tragedy that transcends time. It’s a powerful and unsettling book, even more so in our current age of helicopter parents and tiger moms.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews for numerous publications.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.