Maine’s chief medical examiner has determined that two men whose bodies were pulled from a sewage pump tank in Kennebunkport on Tuesday died from inhaling sewer gases.

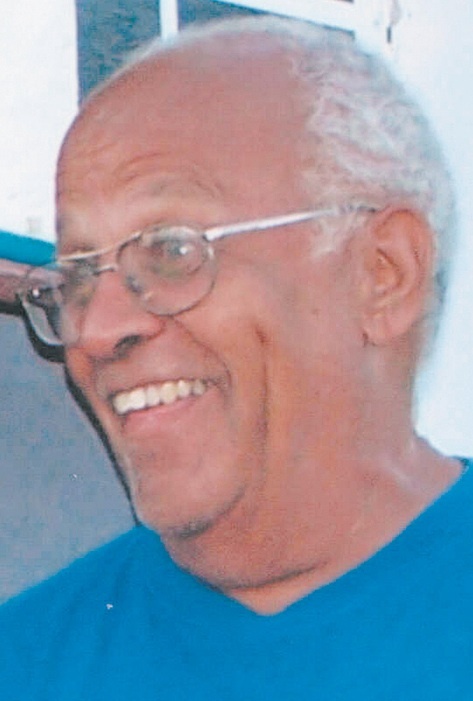

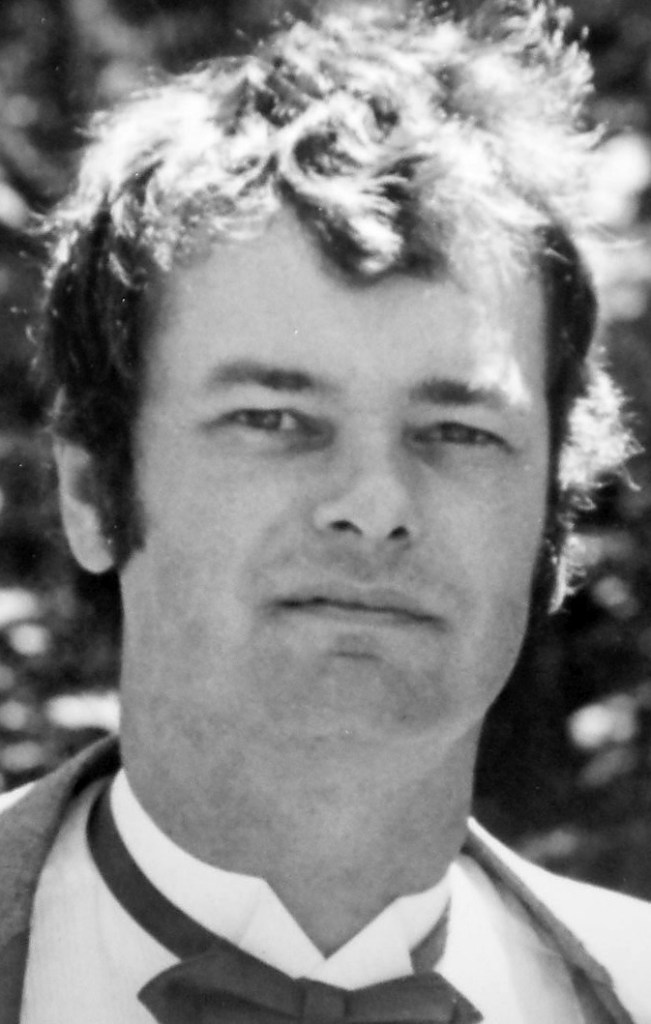

Autopsies done Wednesday on the bodies of Richard Kemp, 70, of Monmouth and Winfield Studley, 58, of Windsor showed they died from “hydrogen sulfide toxicity in a confined space with terminal inhalation of sewage,” said a press release from Kennebunkport police.

Hydrogen sulfide is a toxic gas given off by bacteria in sewage. Its effects are sudden in high concentrations, causing an inability to breathe, unconsciousness and death.

The men were working on a submersible pump in the tank at the Lodge at Turbots Creek. The concrete tank, with its floor 9 feet below the ground, is roughly 4 feet high by 5 feet wide by 6 feet long, accessed by a manhole.

The men were experienced workers who had installed and serviced sewer pumps across the state. Neither one was wearing special breathing apparatus when the bodies were recovered, officials said. One of them was wearing a Tyvex suit.

Officials are awaiting a report from a contractor who was hired to inspect the tank to determine what may have happened.

The federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration plans to review video and photographs taken inside the tank as investigators probe whether an equipment malfunction may have played a role in the men’s deaths.

When the bodies were found just after 11 a.m. Tuesday, the 1,000-gallon tank they were in was overflowing, even though it had been pumped out less than an hour earlier. That would suggest that wastewater from the municipal sewer system had flowed back into the private system, which serves the 26-room hotel where the men were working.

The Kennebunkport Sewer District maintains a 6-inch sewer line that is under constant pressure because the sewage is pumped uphill from the base of Turbots Creek Road.

Kemp and Studley knew the dangers of working in enclosed spaces, and with the gases that can accumulate when sewage is present. They were employed by Stevens Electric and Pump Services of Monmouth, a well-regarded company that services sewage and water pump stations around the state.

The men apparently were replacing the pump for the tank, but the pump they had was the wrong size so they were waiting for a replacement to be delivered, said Police Chief Craig Sanford.

There were no witnesses to the incident. The men were outside the tank while it was being pumped by another contractor, and were in it when he returned from dumping his load, 30 to 45 minutes later.

Kemp’s friend, Paul Fox of Monmouth, said he believes that Kemp and Studley were flooded with water while down in the hole, and that it was an accident and not the result of negligence or a failure to follow correct procedure.

Karen Billups, assistant area director for OSHA, said she cannot comment on specifics of the investigation until it is complete. She said the agency’s investigator will be given a copy of the pictures taken inside the tank, and the report prepared by an investigator retained by the town.

Working in confined spaces is inherently dangerous, say people in the industry. One major hazard in dealing with sewage is hydrogen sulfide. The gas has a “rotten egg” odor, but people can quickly lose the ability to smell it in high concentrations, according to a fact sheet from OSHA.

The fact sheet says that if the gas is present, a work area must be ventilated continually or workers must wear special breathing apparatus.

Workers typically check gas levels before entering a manhole or another confined space, and make sure that any electrical current is turned off and valves are shut to keep liquid from flowing into the space.

“Recognizing we’re entering hazardous or confined spaces, we follow general practices to make sure we do it safely,” said Scott Firmin, director of wastewater for the Portland Water District, which manages four sewage treatment plants and 80 pump stations.

Firmin said he has no direct information about Tuesday’s incident and could not discuss any particular precautions that might have been taken.

The district maintains a confined-space team, which does quarterly training and makes sure that anyone who enters a confined space to work — which happens about once a week — has filled out a checklist of safety steps. The list includes being tethered to equipment above ground, having an attendant monitor them while inside, and taking atmospheric readings before entering.

The meters check for oxygen levels, carbon monoxide, explosive gases and hydrogen sulfide. If hydrogen sulfide levels exceed 10 parts per million, workers won’t enter without breathing equipment.

“It can be dangerous,” Firmin said. “We’re trying through the (confined-space) team to build an understanding and awareness of these issues so we are working safely.”

The OSHA fact sheet warns against trying to rescue someone who has been overcome by hydrogen sulfide unless the rescuer is equipped with breathing apparatus.

Kemp had retired from Stevens Electric, but worked there occasionally on an on-call basis, said his friend, Paul Fox. Kemp installed and replaced pumps that move water and sewage, Fox said. The job typically requires working in a hole.

Kemp’s son, Jeff Kemp, and two of Kemp’s grandchildren, Brian and Shaun Goucher, work for Stevens Electric.

Fox knows a number of Stevens Electric employees and is well acquainted with the family that owns the company.

“I have no doubts whatsoever that Stevens would ever chance a man getting hurt,” he said. “They’re a good company.”

The company has not been cited by OSHA for any infractions, according to the agency’s database.

Kennebec Journal Staff Writer Craig Crosby contributed to this report.

Staff Writer David Hench can be contacted at 791-6327 or at:

dhench@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.