Consider this: The average person’s body contains about 100 trillion cells, but only maybe one in 10 is human.

This isn’t the latest Hollywood horror flick, or some secret genetic engineering experiment run amok.

This, it turns out, is nature’s way: The human cells that form our skin, eyes, ears, brain and every other part of our bodies are far outnumbered by those from microbes, primarily bacteria but also viruses, fungi and a panoply of other microorganisms.

That thought might make a lot of people lunge for the hand sanitizer, at the least. But that predictable impulse may be exactly the wrong one. A growing body of evidence indicates that the microbial ecosystems that have long populated our guts, mouths, noses and every other nook and cranny play crucial roles in keeping us healthy.

Moreover, researchers are becoming more convinced that modern trends — diet, antibiotics, obsession with cleanliness, Caesarean delivery of babies — are disrupting this delicate balance, contributing to some of the most perplexing ailments, including asthma, allergies, obesity, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, cancer and perhaps even autism.

“In terms of potential for human health, I would place it with stem cells as one of the two most promising areas of research at the moment,” said Rob Knight of the University of Colorado. “Everywhere we look, microbes seem to be involved.”

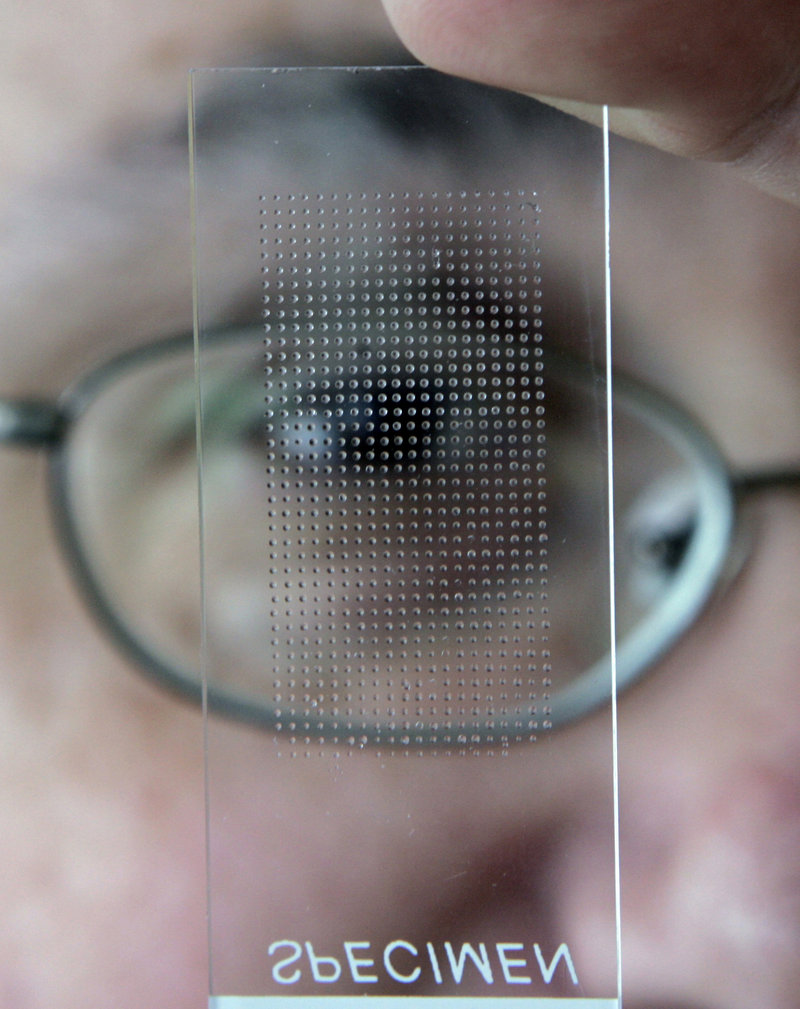

Equipped with super-fast new DNA decoders, scientists are accelerating the exploration of this realm at a molecular level, yielding provocative insights into how these microbial stowaways may wield far greater powers than previously appreciated in, paradoxically, making us human.

“The field has exploded,” said Jeffrey Gordon of Washington University, who pioneered the exploration of humanity’s microbial inhabitants, known as the “microbiome” or “microbiota.”

Some equate these microbial inhabitants to a newly recognized organ. Acquired beginning at birth, this mass of fellow travelers may help steer normal development, molding immune systems and calibrating fundamental metabolic functions such as energy storage and consumption. There are even tantalizing clues they may help shape brain development, influencing behavior.

“The ‘human supraorganism’ is one term coined to describe the human host and all the attendant microorganisms,” said Lita Proctor, who leads the Human Microbiome Project at the National Institutes of Health, which is mapping this world. “There’s been a real revolution in thinking about what that means.”

Investigators are trying to identify which organisms may truly be beneficial “probiotics” that people could take to help their health. Others are finding substances that people might ingest to nurture the good bugs. Drugs may mimic the helpful compounds that these organisms produce.

Doctors have even begun microbiota “transplants” to treat a host of illnesses, including a sometimes-devastating gastrointestinal infection called C. difficile, digestive system ailments such as Crohn’s disease, colitis and irritable bowel disorder, and even in a handful of cases obesity and other afflictions, such as multiple sclerosis.

Many advocates of the research urge caution, noting that most of the work so far has involved laboratory animals or small numbers of patients, many hypotheses remain far from proven and nothing has zero risk.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.