Ten years ago, Jon Hinck was a lawyer representing addicts in a class-action lawsuit against the maker of OxyContin.

It was already clear that the little pills were much more addictive than the company claimed, and that Maine had a new drug abuse epidemic, Hinck said.

“Everywhere you turned were officials saying, ‘We’re getting on top of this problem,’ ” Hinck said. “Ten years later, it hasn’t been getting better. It’s been getting steadily worse.”

Now, as a state legislator from Portland, Hinck is among the state officials and addiction experts who are pushing for a more aggressive effort to cut off the steady flow of prescription painkillers to people who sell and abuse them.

“It’s too damn easy,” he said.

Maine has, in fact, responded to the epidemic with a long list of policies and initiatives. Some, such as tamper-proof prescription pads and overdose prevention campaigns, have made a difference.

Maine is also considered a national leader in collecting and disposing of the unused drugs in medicine cabinets around the state. More collection events will be held around the state on Oct. 29.

But a decade into the effort, there still is limited coordination and communication among the groups that are involved in the problem, including dentists, doctors, hospitals, pharmacies, health insurers, licensing boards, schools, police departments, drug enforcement agencies and state officials.

“This is a silo-breakdown kind of problem,” said Dr. Tamas Peredy, an emergency medical physician in Portland.

Police arrest dealers, for example, but don’t warn the doctors who are writing prescriptions for them. On the other hand, doctors who catch someone abusing prescriptions don’t typically tell the police.

The state now tracks virtually every painkiller prescription filled in Maine, but it hasn’t committed the resources to use the information aggressively.

Doctors can check a database to make sure their patients aren’t getting the same drugs from other doctors, but most never look. Police, meanwhile, need a court order to get access to the records.

“A lot of things have to do with resources and a lot of it has to do with identifying things people can do across jurisdictions,” said William Savage, an assistant state attorney general.

Coordination has improved in some areas.

State-funded Overdose Prevention Projects in Portland, Bangor and Waterville routinely bring together people from the law enforcement, treatment and medical communities to respond to new trends.

Treatment providers and police in Maine’s midcoast also meet periodically to share information.

The Maine Medical Association works with drug enforcement agents and state officials to train Maine doctors how to help legitimate pain patients while reducing abuse and addiction.

And the Maine Drug Enforcement Agency, which hasn’t been able to afford a full-time prescription drug unit since the 1990s, has been using temporary federal funds to employ two full-time prescription drug agents — one in Aroostook County and one in Penobscot and Piscataquis counties. While they carry out undercover stings and drug raids, their primary duty is to talk with physicians and pharmacists to encourage cooperation and gather leads.

“(It) is breaking down those barriers,” said MDEA Director Roy McKinney.

The federal funding is running out, so McKinney is trying to keep the work going within his own payroll.

Chris Gardner, the prescription drug agent for Penobscot and Piscataquis counties, spent part of this summer warning pharmacists about narcotic prescriptions written in Florida. Dealers have been driving or flying south to get prescriptions from clinics known as “pill mills,” then filling the prescriptions in Bangor and other communities and selling the pills for huge profits.

Gardner doesn’t tell pharmacists they can’t fill such prescriptions, but some said they won’t fill them, after hearing about the scheme. Some even called Gardner the next time they got such a scrip, he said.

“We’re under no misconception that we are going to enforce our way out of this problem,” Gardner said. “Sharing information is the key to slowing it down.”

Now, Gardner is helping to develop a Diversion Alert Program in northern Maine. It will send monthly bulletins to doctors with the names of people who have been arrested or charged with possessing or selling prescription pills. He hopes it will give prescribers another tool to weed out patients who may be faking pain and diverting the medication.

It’s not clear how to spread the idea statewide because of the sheer number of arrests in places such Penobscot and Cumberland counties. But some say it is the kind of coordination needed at the state level.

“A lot has been done. I don’t think it’s sufficiently coordinated,” said Hinck, the Portland lawmaker and former class-action lawyer.

Some of Hinck’s clients back in 2001 did win modest settlements, he said. PurduePharma, the maker of OxyContin, eventually faced criminal fines and paid a $19.5 million civil settlement to 26 states, including $719,000 for Maine.

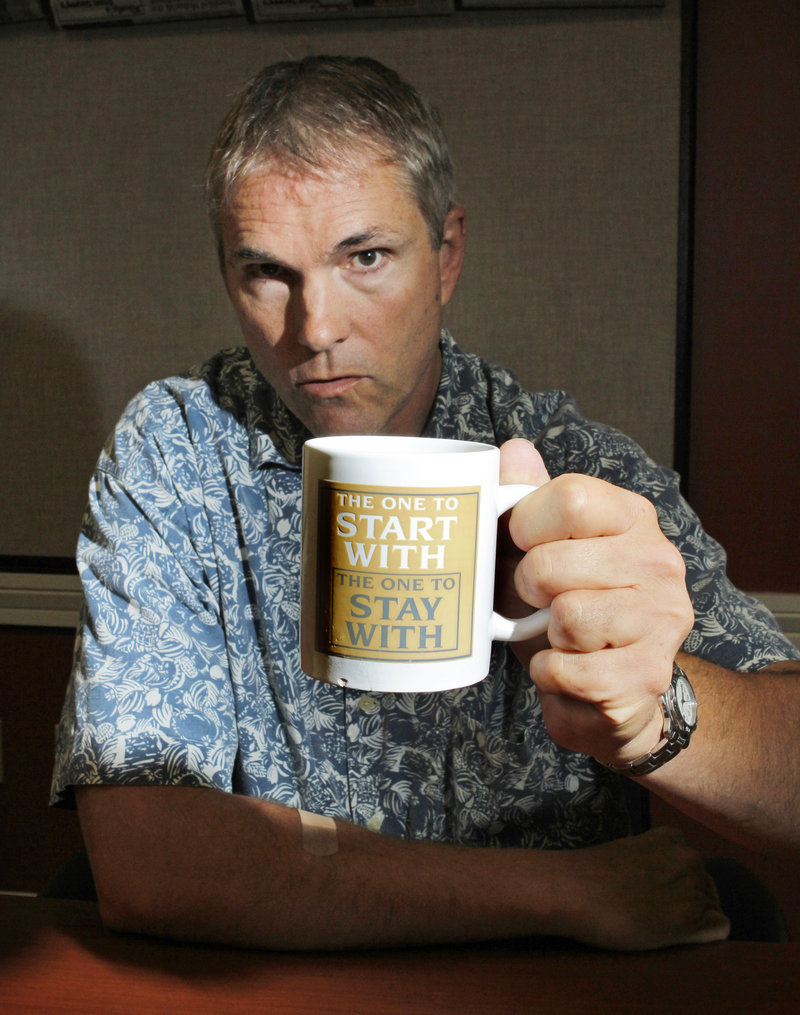

Hinck said he remembers the struggles of the addicts he represented, and he keeps a mug that was part of PurduePharma’s initial marketing campaign to doctors. It reads: “OxyContin: The one to start with. The one to stay with.”

When he became a legislator and learned how much the problem had grown, Hinck said, he researched what was happening in other states.

He proposed legislation early this year that would have mandated new procedures for prescribers and pharmacies. Among other things, it called for all prescribers to join Maine’s drug-monitoring database and all pharmacists to check identifications to make sure patients didn’t forge prescriptions. Both practices are now voluntary and sporadic.

The proposal was based on legislation enacted recently in Washington state and considered the most aggressive in the nation. It failed in the Maine Legislature.

The medical community, and ultimately lawmakers, said the bill went too far by mandating a range of medical practices. It would have required that some patients be referred to pain management specialists, for example, even though Maine has few such physicians.

Doctors must be free to care for their patients and adapt to new treatments and care standards, opponents said. Cumbersome mandates also might lead some doctors to stop prescribing the painkillers to patients who legitimately need them, some warned.

“I think doctors do need to recognize that they have some responsibility for the problem of diversion and addiction, but my concern about legislating the behavior is that it may have unintended adverse consequences for patients,” said Dr. Stephen Hull, co-director of the Mercy Pain Center in Portland.

Pharmacies viewed the mandated ID checks as a burden on customers.

Pharmacists can already request identification if they are suspicious, said Douglas Carr, an attorney who represents Rite-Aid of Maine. But they don’t want to make customers wait unnecessarily, he said. “If you do that for everyone, you’re going to have some very unhappy customers, and 95 percent of the customers are legitimate.”

While it rejected the mandates, the Legislature created a study group to find ways for the medical community to tighten up access to the pills. The group, which includes doctors, addiction experts and lawmakers, is due to report to the Legislature in December.

“We need to be thinking a lot harder about what we’re doing and whether it’s really needed, and not giving a lot more pills than patients really need,” said Rep. Linda Sanborn, a retired physician and a Democratic lawmaker from Gorham who serves on the study group.

Some doctors support new requirements.

“This is such a big social problem that I think doctors should suck it up” and check their patients’ prescriptions, said Dr. Ira Stockwell, who treats addicts as part of his primary care practice in Westbrook.

Stockwell has written letters to the governor and others urging ID checks at pharmacies because of the ease with which prescription sheets can be stolen and forged. “That is so important. They need to hold up customers for that,” he said.

Members of the study group solidly opposed such mandates at a recent meeting.

“We’ll get a whole lot more done by educating. … and getting voluntary support,” said Carr, Rite-Aid’s representative, during the meeting. “I think you have to really have demonstrated ongoing ignoring of the issues before you even get to a decision of mandates.”

The study group doesn’t include law enforcement experts or recovering addicts. Several members said they were disappointed that some important players in the medical community, such as dentists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and osteopaths, were not participating.

“It would be a great thing if all of them were there,” said Sanborn.

A more diverse group is about to convene next week, and may come up with its own proposals.

Maine Attorney General William Schneider will host a daylong summit on prescription drug abuse Oct. 25 in Northport. The summit will bring together leaders in the fields of prevention, treatment, education, enforcement and public policy to develop an action plan for the state, said Schneider. He said he hopes to include the perspective of recovering addicts.

Schneider, who prosecuted drug cases in the Attorney General’s Office in the 1990s, said he wants to improve coordination and move beyond fingerpointing.

“We’re not going to engage in that. We’re assuming that everybody there wants to make the situation better and we’re going to look at the costs of not doing anything,” he said. “I hope to end up with three or four specific, concrete things we can do.”

Guy Cousins, director of Maine’s Office of Substance Abuse, said the problem is too big and complex for any one group to tackle. It requires prevention education, responsible prescribing practices, medication tracking, drug collections and disposal, law enforcement, and adequate treatment and recovery services.

“If you only have one hook to hang stuff on, not a lot is going to hang on it,” Cousins said. “Everybody’s got part of the problem. Everybody’s got to have a part of the solution.”

Staff Writer John Richardson can be contacted at 791-6324 or at: jrichardson@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.