The other day, a friend gave me a card from master woodcarver Robert Jones of Thomaston depicting a working French horn that he had made out of wood rather than brass. (Search for “58scallop” on YouTube to see it yourself.) The instrument is most certainly a tour de force, but I was wondering why anyone would go to all that trouble.

Then I looked at it from a little distance and found that the French horn is a work of art in itself, aside from the sounds it makes. The contrast of multiple curves, bell, circles and straight lines is somehow deeply satisfying.

Perhaps Jones’ next endeavor should be a tuba, which artist Rene Magritte turned into a collection of intestines in his painting “Le temps menacant.” Jones has already carved a working trumpet and trombone.

Perhaps aesthetics has as much to do with the design of an instrument as sound quality. There is really no acoustic reason why a violin, viola, cello or bass viol looks the way it does except for its resemblance to the female form. Near-perfect violin forms have been found from the Cycladic period of Greece (5,000-4,000 B.C.E.). They are thought to have been idols of a mother goddess.

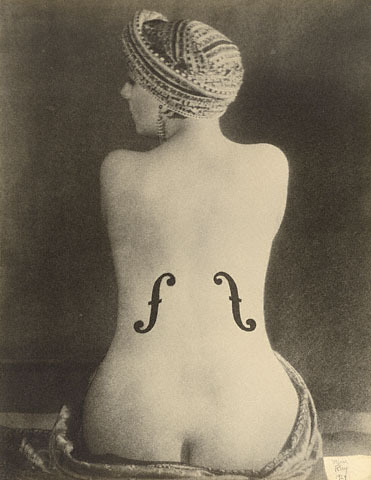

Artists and musicians have always known this. Witness photographer Man Ray’s alteration of a postcard entitled “Violon d’Ingres,” by painting f-holes on the back of a female nude. Ingres has the first laugh, however, with his portrait of Paganini cradling his violin.

The harp is yet another ancient shape, reduced to its most basic form — a triangle with a curved hypotenuse, depicted in another Cycladic sculpture from 3,000 B.C.E. The modern harp has more florid decorations (the frame of the Cycladic version is a snake), but even the most primitive have bells and whistles that have nothing to do with the sound.

The woodwinds have their own beauty. I like to have a flute on the mantelpiece even though I can’t play a note on it, as an example of the aesthetic appeal of the machine. The bassoon, the oboe and the clarinet are also works of art that have evolved from simple origins, both musically and aesthetically.

I have often wondered if the side-blown flute replaced the recorder because of its greater range and sound quality, or because it could be played with propriety by a female. Women were also excluded from violin-shaped instruments for a long time.

The earliest instrument, far predating the harp, is the end-blown flute, examples of which have been found in pre-historic cave dwellings, usually made from a hollow bone.

The iconic musical instrument depicted most in the arts is the grand piano, which can furnish an entire room by its presence alone. Swedish poet Tomas Transtromer pictures it in “Balakirev’s Dream” this way: “The black grand piano, the gleamy spider/ Stood quivering in the center of its music net.” Uprights somehow just won’t do, unless they happen to be virginals or harpsichords.

It’s strange that so simple and commanding a form has evolved only recently from the ornately decorated baroque cases that used to house the strings and sounding board. Or that uprights, some of which are merely grand piano frames stood on end, should be banished to the studio, in spite of their fine sound quality. Of course the grand, once again, has a feminine shape, at least on one side, combined with a masculine attitude.

An instrument that has devolved aesthetically is the drum. Shiny and utilitarian, it still appears often in art, as in Marcel Duchamp’s “The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even.” African versions, however, were sculptures that testify to the reverence in which it was held.

Christopher Hyde is a writer and musician who lives in Pownal. He can be reached at:

classbeat@netscape.net

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.