HELENA, Mont. — A notorious “mountain man,” who abducted a world-class athlete in 1984 to keep as a wife for his son, once wrote that blame for the “incident” lies with her and a would-be rescuer whom he shot and killed. Don Nichols undoubtedly will need to be more contrite later this month in front of the historically stern Montana Parole Board.

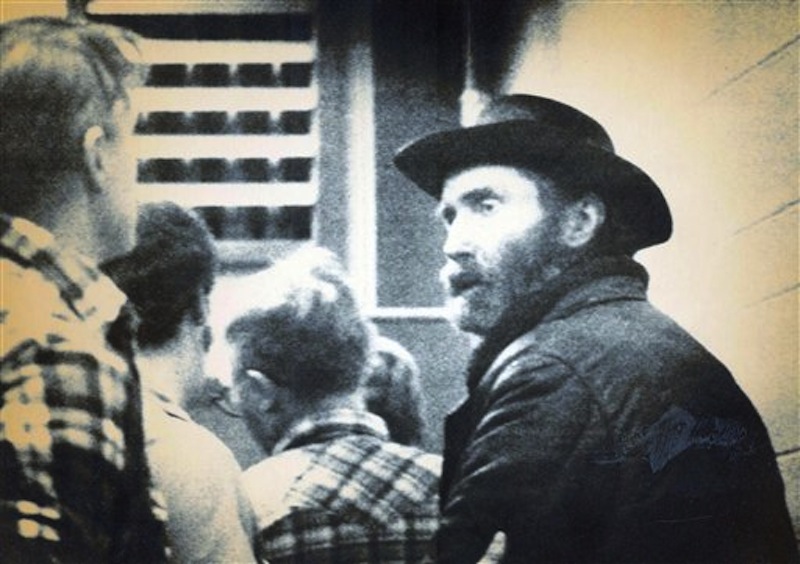

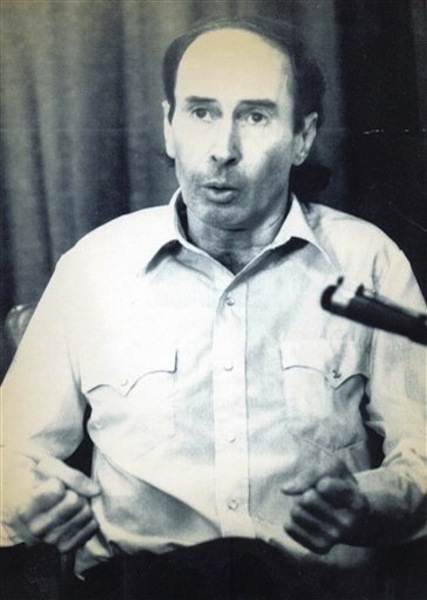

Nichols gained international notoriety for the bizarre crime and prolonged manhunt in the wilderness northwest of Yellowstone National Park that ended when a sheriff stormed his camp. He is now a frail, 81-year-old convict with a weak chin whose 150 pounds stretch over a six-foot frame.

Nichols and his son, Dan Nichols, were known to spend long stretches in the mountains living off the land. Prior to the abduction, they had lived for a year poaching game and growing hidden gardens at various camps they set up — earning them both a “mountain man” moniker they embraced.

The elder Nichols comes up for parole April 27.He has a good track record in prison, where he has worked on the yard crew, and over the years has reportedly become a bit more apologetic for taking Kari Swenson.

But for years after the crime, he wasn’t.

“We more or less only intimidated Kari into coming with us. We were only going to keep her with us for a few days if it didn’t work out,” Nichols wrote in a collection of letters, journals and lengthy manuscript dating from the late 1980s and early 1990s now housed at the University of Montana library. “Also, we treated her very humanely all the time, in fact cordially, except for the unusual circumstances. I did not hit Kari. The chain involved was a real lightweight chain. One end was fastened comfortably around her waist and other end around a tree.”

Nichols sent the manuscript, which had previously been released in hopes of publishing a book, along with his personal collection of letters and notes to the library, intending for them to be preserved.

Don Nichols’ crime, however, still looms large for his victims and many in the Bozeman-area community who want to make sure he doesn’t get out of prison. And the collection of writing he sent to the library reveals a disdain for laws, modern life and seemingly little regret for his crime — suggesting that “flatlanders” may just forget about what he referred to as the “incident.”

Nichols’ new parole hearing comes five years after another request for parole was met with close to 200 letters in opposition from people who strongly remembered the kidnapping and five-month long manhunt that remains one of the state’s most notorious crimes.

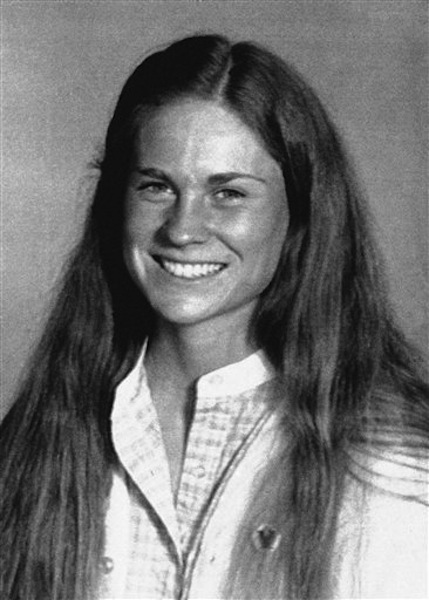

Nichols is serving an 85-year sentence for kidnapping Swenson, then a 22-year-old world-class biathlete. He also was convicted of killing Swenson’s would-be rescuer, Alan Goldstein.

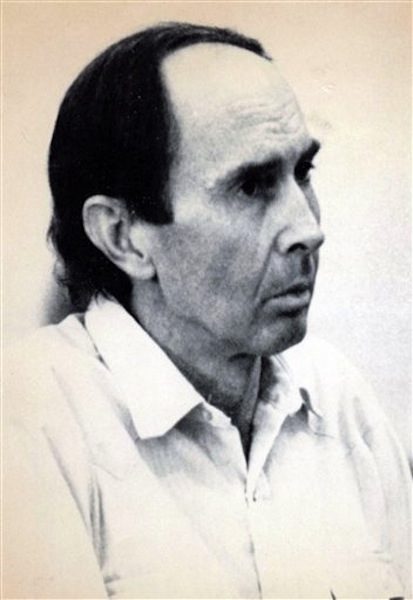

The parole hearings comes as Dan Nichols — paroled in 1991 from his kidnapping and assault sentence received for his role in the infamous crime — is in trouble with the law again. Jefferson County officials issued an arrest warrant last month for the younger Nichols after he failed to show up for a pretrial hearing in a drug case.

The younger Nichols faces many more years in prison after getting caught last summer at a rock concert with possession of marijuana with the intent to sell it, and allegedly resisting arrest.

Has he escaped into the mountains again?

“I wouldn’t want to speculate,” said Jefferson County attorney Mathew Johnson.

Back in the 1980s, the abduction and manhunt gripped the state — and nation.

In July of 1984 the Nichols ambushed Swenson with guns while she was on a training run in the mountains above the resort town of Big Sky.

They forced her into the woods and kept her chained her to a tree most of the time when would-be rescuers stumbled upon the camp. In the melee, Dan Nichols accidentally shot Swenson. An armed standoff ensued, and the elder Swenson gunned down Alan Goldstein.

The Nichols left Swenson severely wounded and escaped into the woods. The experienced woodsmen evaded capture for five months living in the Madison Range, until a daring Madison County sheriff and former bronco buster named Johnny France took it upon himself to follow a tip and gave chase alone before storming the Nichols camp and forcing their surrender.

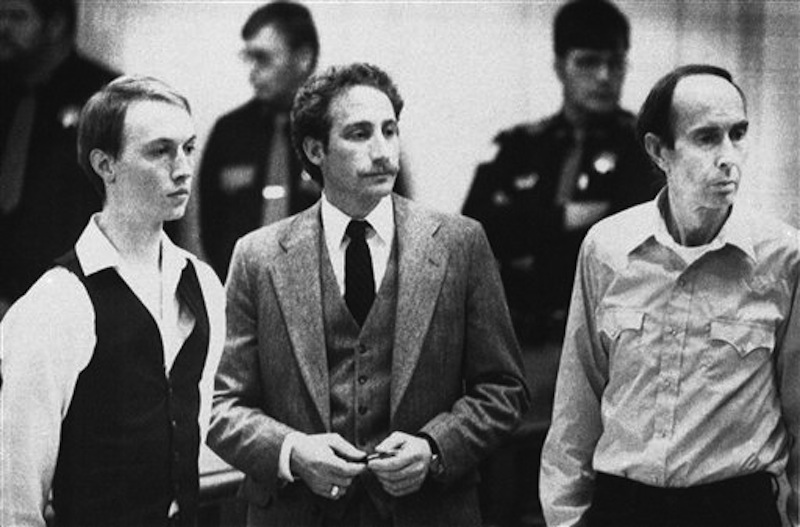

Swenson, despite diminished lung capacity from the gunshot wound, went on to win a bronze medal in the world biathlon championships. The Nichols faced a prosecutor, Marc Racicot, who would later become governor and a jury who didn’t buy their argument that modern society misunderstood their mountain man ways.

The sensational tale made the cover of national newsmagazines, spawned two books and a TV movie “The Abduction of Kari Swenson.”

Nichols had a far different take on the series of events, believing he was being unfairly judged by people who didn’t understand nature or the mountains.

His “manuscript”, written in tight cursive and finished in 1992, trashed modern society’s pursuit of material goods, quoted famed environmentalist John Muir as he extols life in the woods and Friedrich Nietzsche’s view of human nature.

The writing is filled with a yearning for pioneer days that Nichols believed more natural, castigates businessmen and politicians as the real thieves and killers, and claims “civilization is the insane byproduct” of rules and laws. All conspire to trample freedom, he argued, like the “virtual Nazis” running the country.

“The deer on the mountains don’t spend much time worrying that there are a lot of things that might have notions on their freedom,” he wrote. “Neither do Danny and I worry about such things.”

His sketches include his son walking through the woods carrying a bow. One — that depicts events just one day prior to the Swenson abduction — shows a tranquil pond in the woods, with a tree inscribed “Dan and Don live in these mountains. July 14, 1984.”

His recollection of the abduction, in writing that stretches from the time of the trial to after he spent several years in prison, appears to show no remorse whatsoever. Even after the shootings, he and his son continued to live in the woods seemingly with little care, or knowledge, that a manhunt was under way.

“In the summer of 1984, after the incident with Kari Swenson, Danny and I felt safe in our mountains, as usual, and spent most of our time wishing for pretty sunsets, planning the next day’s activities, or talking over the continuous adventure of hunting, camping, and other things that is our life in the mountains,” he wrote. “Maybe we should have thought about the flatland people more. Maybe we should have realized the truth wouldn’t be told.”

He goes on to argue his victims are to blame for the events, and believed it was being twisted by a “corrupt” media.

“Regardless of what the other facts are, if Kari had not been up at Ullery’s Lake in the manner she was, Goldstein wouldn’t have been killed by me,” the elder Nichols once wrote. “That’s a fact and her subconscious mind will always tell her that. So what does she think of herself now that her ‘hero’ is dead?”

Nichols even felt that in some way his actions “inspired” some Montanans and “scared the pants off totalitarians all over America, those who have been running things since the insanity of the Reagan presidency started.”

His regret was missing life in the mountains. After a few years in prison, Swenson wrote longingly about the names he and his son had given to various camps.

“I think of a thousand beautiful sunsets and sleep so sweet we could taste it,” he wrote in 1987. “There must always be mountain men.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.