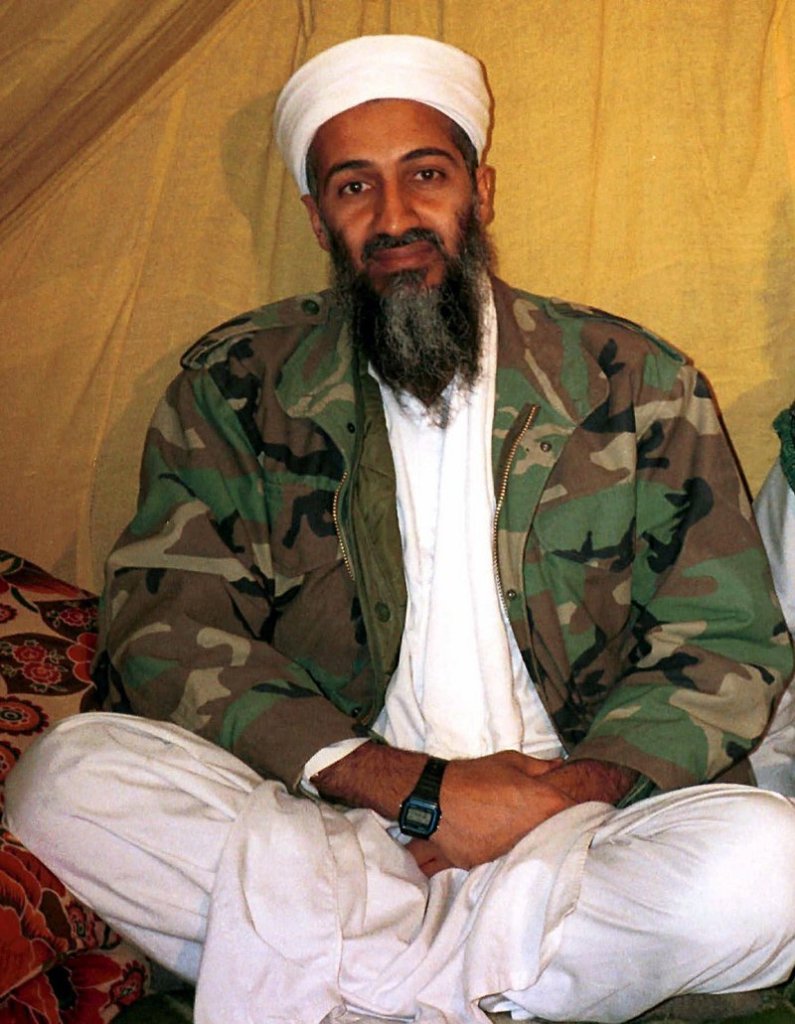

A year ago, U.S. Navy SEALs slipped into a heavily fortified compound in Pakistan and killed the face of international terrorism. There is a growing fear, however, that Osama bin Laden’s death didn’t even seriously wound the international terror threat.

This past decade — as al-Qaida’s core leadership was hunted, scattered and disrupted in Afghanistan and Pakistan — a number of sympathetic groups and individuals sprang up around the world. In the year since his death, their importance in this shadow world has grown.

Richard Fadden, the head of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, said that this many-headed beast is expected to strike more and more frequently in coming years, and he cited the difficulty of identifying “lone wolf” terrorists — small groups or individuals who self-radicalize.

“It’s not easy,” he told a Canadian Senate committee last week. “These individuals seem to be a mix of terrorists and people who simply have very big personal problems.”

An unexpected example emerged in a Norwegian courtroom: Anders Behring Breivik, the anti-immigration nationalist on trial for the murders of 77 people, admitted that he closely studied al-Qaida’s methods. He called the group “the most successful revolutionary movement in the world.”

Anti-terror experts see the al-Qaida influence extending even as the core of the organization is thought to be down to an estimated 100 or fewer followers in its traditional home of Afghanistan and Pakistan’s ungoverned tribal areas. A Pentagon spokesman said that even that estimate could overshoot the total number who sleep in Afghanistan on any given night, which might be no more than a few dozen.

Throughout the world, offshoot groups have adopted the al-Qaida label. They’ve pledged cooperation, shared money and weapons, often trained together or advised each other on al-Qaida methods, and shared both strict Islamist roots and a fervent hatred for the West.

Rather than waiting for orders from above, these groups act first, then give credit to the mother organization, which in turn often offers praise that bolsters the affiliate group’s standing. U.S. and international forces have battled al-Qaida in Iraq for years, and AQI is thought to be trying to make inroads in the uprising against President Bashir Assad in neighboring Syria.

Experts said that five other such groups are considered the most dangerous, or the most capable: al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula, based in Yemen; al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, based in Algeria and Mali; Lashkar-e-Taiba of Pakistan; al-Shabaab of Somalia; and Boko Haram, a relatively young Nigerian militancy.

They organize on the Web and use social media to communicate and recruit. They’re in contact with each other, offering advice, money, weapons and planning. They’ve been involved in attempted attacks in New York’s Times Square and aboard a Detroit-bound jetliner, as well as assaults in London, Mumbai and Fort Hood, Texas.

The groups appear to have direct ties to al-Qaida’s central organization.

“What we’re facing today is a much, much larger global threat,” said Seth Jones, an expert at the RAND Corp. who’s advised the Pentagon on Afghanistan and Pakistan. “It’s a more dispersed threat. The threat is decentralizing to a broad network of groups. Al-Qaida inspires, but doesn’t control, and they work with locals.”

The meaning of that threat: Massive attacks such as those on 9/11 are unlikely to be repeated. But expect smaller-scale attacks — the “strategy of a thousand cuts,” it was called in AQAP’s slick online propaganda magazine Inspire.

A deadly example came in 2009 with the rampage at Fort Hood, Texas, where Army psychiatrist Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan, allegedly radicalized online by AQAP, is accused of shooting dead 13 soldiers. His trial is scheduled to begin in August.

Experts note that these groups have largely localized agendas. Generally, they’re looking to impose Islamic Shariah law and, if not overthrow a local government, carve out a space in which to operate in their home country.

But the al-Qaida model encourages ideological hybridization: think locally, act globally.

Al-Shabaab, which began in 2006 as the militant wing of a group of Islamist courts that briefly ruled southern Somalia, has also shown global ambitions — recruiting dozens of youths, mostly from Minnesota but also from Alabama, California and Ohio, to fight an insurgency against Somalia’s weak government and an African Union peacekeeping force.

But Tom Sanderson, co-director of the Transnational Threat Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, says that one of the most puzzling questions for those who track international terrorism is why al-Shabaab — so far — hasn’t lashed out at the United States.

“The Shabaab network inside the United States is tailor-made for what al-Qaida wants to accomplish in this country,” Sanderson said. “They have ties to al-Qaida, they have the rhetoric. It’s not a very big stretch to turn that into attacks in the United States.”

To date, al-Shabaab’s efforts have mainly focused in Somalia. In Pakistan, Lashkar-e-Taiba — the Army of the Pure — has been around since 1993 and has been focused for most of that time on India. Its biggest attack — a November 2008 assault on a hotel and other sites frequented by tourists in India’s commercial capital Mumbai — killed 164 people, including six Americans.

The group’s anti-Western rhetoric and alleged ties to Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence directorate spy agency have fueled fears that it will soon look to strike farther afield — perhaps to the United Kingdom, where Sanderson noted there is “a ready-made diaspora, including youths who’ve become disenchanted with the West.”

Similar reasoning applies to al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, which is thought to want to strike outside Africa and particularly in France, the former colonial master in the region. The Algeria-based group has been using money from kidnapping and smuggling to buy up weapons from the caches of former Libyan strongman Moammar Gadhafi. Military and counterterrorism experts believe AQIM played a role in the success of the Tuareg rebellion in Mali, which touched off a military coup in the West African nation this spring.

The group has also thought to have gotten some help from Nigeria’s Boko Haram, a worrying addition to international terrorism whose 115 attacks killed 550 people in Nigeria last year alone. The name — which translates to “Western education is forbidden” — tells of the group’s disdain for the West. Experts fear that its participation in Mali shows it’s willing to operate outside its national borders.

“What is happening in Mali started as a nationalist, separatist movement, but has it been co-opted by a collection of Islamists?” said J. Peter Pham, director of the Atlantic Council’s Michael S. Ansari Africa Center.

Experts agree that the main emerging danger is these localized groups expanding their ambitions outside their homelands. One year after bin Laden, international terror may no longer have a face, but its teeth are still sharp.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.