LOS ANGELES — Ray Bradbury anticipated iPods, interactive television, electronic surveillance and live, sensational media events, including televised police pursuits — and not necessarily as good things.

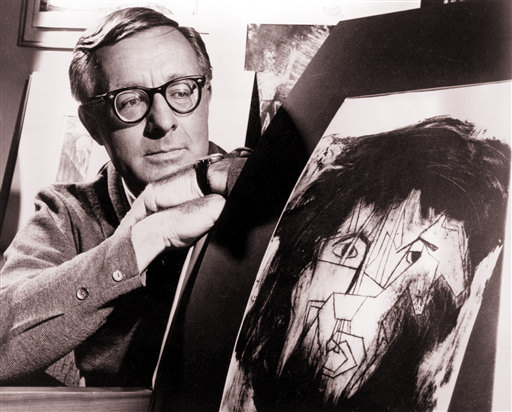

The science fiction-fantasy master spent his life conjuring such visions from his childhood dreams and Cold War fears, spinning tales of telepathic Martians, lovesick sea monsters and, in uncanny detail, the high-tech, book-burning future of “Fahrenheit 451.”

All of them, in short stories, in the movie theater and on the television screen, would fire the imaginations of generations of children and adults across the world. Years later, the sheer volume and quality of his work would surprise even him.

“I sometimes get up at night when I can’t sleep and walk down into my library and open one of my books and read a paragraph and say: ‘My God, did I write that? Did I write that?’ Because it’s still a surprise,” Bradbury said in 2000.

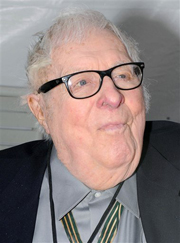

Bradbury, who died Tuesday night at age 91, was slowed in recent years by a stroke that meant he had to use a wheelchair. But he remained active over the years, turning out new novels, plays, screenplays and a volume of poetry.

Just this week he wrote in The New Yorker about discovering science fiction when he was 7 or 8 years old.

“It was one frenzy after one elation after one enthusiasm after one hysteria after another,” he wrote. “I was always yelling and running somewhere, because I was afraid life was going to be over that very afternoon.”

He wrote every day in the basement office of his home in the Cheviot Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles and appeared from time to time at bookstores, public library fundraisers and other literary events around Los Angeles.

It was a career he often said was inspired by a chance meeting in 1932 with a carnival magician called Mr. Electrico who, at the end of his performance, reached out to the captivated 12-year-old, tapped him with his sword and said, “Live forever!”

“I decided that was the greatest idea I had ever heard,” Bradbury said later. “I started writing every day. I never stopped.

His writings ranged from horror and mystery to humor and sympathetic stories about the Irish, blacks and Mexican-Americans. Bradbury also scripted John Huston’s 1956 film version of “Moby Dick” and wrote for “The Twilight Zone” and other television programs, including “The Ray Bradbury Theater,” for which he adapted dozens of his works.

“What I have always been is a hybrid author,” he said in 2009. “I am completely in love with movies, and I am completely in love with theater, and I am completely in love with libraries.”

Much of Hollywood was also in love with him, and tributes from actors, directors and other celebrities poured in upon news of his death.

“He was my muse for the better part of my sci-fi career,” director Steven Spielberg said in a statement. “He lives on through his legion of fans. In the world of science fiction and fantasy and imagination, he is immortal.”

Bradbury broke through in 1950 with “The Martian Chronicles,” a series of intertwined stories that satirized capitalism, racism and superpower tensions as it portrayed Earth colonizers destroying an idyllic Martian civilization.

That book, “Fahrenheit 451” and others continue to be taught at high schools and universities around the country.

“He was always my favorite science fiction writer because what he did was rooted in reality. He never got really out there,” writer Tom Wolfe said.

Like Arthur C. Clarke’s “Childhood’s End” and the Robert Wise film “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” ”The Martian Chronicles” was a Cold War morality tale in which imagined lives on other planets serve as commentary on human behavior on Earth. “The Martian Chronicles” has been published in more than 30 languages, was made into a TV miniseries and inspired a computer game.

“The Martian Chronicles” prophesized the banning of books, especially works of fantasy, a theme Bradbury would take on fully in the 1953 release, “Fahrenheit 451.” Inspired by the Cold War, the rise of television and the author’s passion for libraries, it was an apocalyptic narrative of nuclear war abroad and empty pleasure at home, with firefighters assigned to burn books instead of putting blazes out (451 degrees Fahrenheit, Bradbury had been told, was the temperature at which texts went up in flames).

It was Bradbury’s only true science-fiction work, according to the author, who said all his other works should have been classified as fantasy. “It was a book based on real facts and also on my hatred for people who burn books,” he told The Associated Press in 2002.

A futuristic classic often taught alongside George Orwell’s “1984” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World,” Bradbury’s novel anticipated today’s world of iPods and electronic surveillance. Francois Truffaut directed a 1966 movie version and the book’s title was referenced — without Bradbury’s permission, the author complained — for Michael Moore’s documentary “Fahrenheit 9-11.”

Although involved in many futuristic projects, including the New York World’s Fair of 1964 and the Spaceship Earth display at Walt Disney World in Florida, Bradbury was deeply attached to the past. He refused to drive a car or fly, telling the AP that witnessing a fatal traffic accident as a child left behind a permanent fear of automobiles. In his younger years, he got around by bicycle or roller-skates.

“I’m not afraid of machines,” he told Writer’s Digest in 1976. “I don’t think the robots are taking over. I think the men who play with toys have taken over. And if we don’t take the toys out of their hands, we’re fools.”

Bradbury’s literary style was honed in pulp magazines and influenced by Ernest Hemingway and Thomas Wolfe, and he became the rare science fiction writer treated seriously by the literary world. In 2007, he received a special Pulitzer Prize citation “for his distinguished, prolific and deeply influential career as an unmatched author of science fiction and fantasy.” Seven years earlier, he received an honorary National Book Award medal for lifetime achievement, an honor given to Philip Roth and Arthur Miller among others.

Other honors included an Academy Award nomination for an animated film, “Icarus Montgolfier Wright,” and an Emmy for his teleplay of “The Halloween Tree.” His fame even extended to the moon, where Apollo astronauts named a crater “Dandelion Crater,” in honor of “Dandelion Wine,” his beloved coming-of-age novel, and an asteroid was named 9766 Bradbury.

Born Ray Douglas Bradbury on Aug. 22, 1920, in Waukegan, Ill., the author once described himself as “that special freak, the man with the child inside who remembers all.” He claimed to have total recall of his life, dating even to his final weeks in his mother’s womb.

His father, Leonard, a power company lineman, was a descendant of Mary Bradbury, who was tried for witchcraft at Salem, Mass. The author’s mother, Esther, read him the “Wizard of Oz.” His Aunt Neva introduced him to Edgar Allan Poe and gave him a love of autumn, with its pumpkin picking and Halloween costumes.

“If I could have chosen my birthday, Halloween would be it,” he said over the years.

Nightmares that plagued him as a boy also stocked his imagination, as did his youthful delight with the Buck Rogers and Tarzan comic strips, early horror films, Tom Swift adventure books and the works of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells.

“The great thing about my life is that everything I’ve done is a result of what I was when I was 12 or 13,” he said in 1982.

Bradbury’s family moved to Los Angeles in 1934. He became a movie buff and a voracious reader. “I never went to college, so I went to the library,” he explained.

He tried to write at least 1,000 words a day, and sold his first story in 1941. He submitted work to pulp magazines until he was finally accepted by such upscale publications as The New Yorker. Bradbury’s first book, a short story collection called “Dark Carnival,” was published in 1947.

He was so poor during those years that he didn’t have an office or even a telephone. “When the phone rang in the gas station right across the alley from our house, I’d run to answer it,” he said.

He wrote “Fahrenheit 451” at the UCLA library, on typewriters that rented for 10 cents a half hour. He said he carried a sack full of dimes to the library and completed the book in nine days, at a cost of $9.80.

Although some academics doubted that account, saying he could not have created such a masterpiece in such a rapid, seemingly cavalier fashion, Bradbury maintained in several interviews with The Associated Press over the years that that was exactly how he did it.

Few writers could match the inventiveness of his plots: A boy outwits a vampire by stuffing him with silver coins; a dinosaur mistakes a fog horn for a mating call (filmed as “The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms”); Ernest Hemingway is flown back to life on a time machine. In “The Illustrated Man,” one of his most famous stories, a man’s tattoo foretells a horrifying deed — he will murder his wife.

A dynamic speaker with a booming, distinctive voice, he could be blunt and gruff. But Bradbury was also a gregarious and friendly man, approachable in public and often generous with his time to readers as well as fellow writers.

In 2009, at a lecture celebrating the first anniversary of a small library in Southern California’s San Gabriel Valley, Bradbury exhorted his listeners to live their lives as he said he had lived his: “Do what you love and love what you do.”

“If someone tells you to do something for money, tell them to go to hell,” he shouted to raucous applause.

Until near the end of his life, Bradbury resisted one of the innovations he helped anticipate: electronic books, likening them to burnt metal and urging readers to stick to the old-fashioned pleasures of ink and paper. But in late 2011, as the rights to “Fahrenheit 451” were up for renewal, he gave in and allowed his most famous novel to come out in digital form. In return, he received a great deal of money and a special promise from Simon & Schuster: The publisher agreed to make the e-book available to libraries, the only Simon & Schuster e-book at the time that library patrons were allowed to download.

Bradbury is survived by his four daughters, Susan Nixon, Ramona Ostergren, Bettina Karapetian and Alexandra Bradbury. Marguerite Bradbury, his wife of 57 years, died in 2003.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.