The Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockport is celebrating its 60th anniversary. It’s a notable occasion in the art scene of Maine, and CMCA has introduced it with a beautiful exhibition. The Honors Exhibition is a generous opportunity to reflect on the current work of its five honorees — John Bisbee, Katharine Bradford, Frederick Lynch, Todd Watts and Mark Wethli.

I emphasize that opportunity, because reflection is not a common ingredient in large shows. Here, the pace of the presentation, the limitation of the work to what the artists are currently doing, the fact that the artists are for the most part long-familiar and their work is within easy comprehension, give the show its tone. So it comes to us as a tonic.

It’s buoyant; there’s plenty of time to look at the art — enough to form lasting impressions of specific works. I’ve seen the show twice, and certain of its works sustain themselves vividly.

Having said all this, it is these exact qualities that make the event difficult to review. The artists are so perennial, so written-about in so many journals, that offering fresh insights requires a mood that is not always available. But the show calls for reflection, so I will reflect.

John Bisbee stops you in your tracks. His pieces achieve a balance between the brutality of the medium — steel — and his ability to endow it with grace, however uneasy that quality may be.

Hammering 12-inch spikes into celebratory wreaths or bending steel bars into baroque insubstantialities civilizes the material, but it is not to be trusted. Steel comes to us as a product normal to other purposes, and its history is too clear to have faith in its acquiescence. The artist can disguise the material into a masquerade of something else, exploit its obduracy or travel a difficult middle ground.

It is in that middle that Bisbee’s work resides, and much of it strikes me as small miracles. In those pieces, there is a balance between the hostility of the material and its aesthetic perfectibility, its common usage and its reluctance to accede to art. Achieving a balance between the conventions of beauty and the public suspicion of the material is Bisbee’s grand accomplishment.

Katherine Bradford has acquired near-iconic status in Maine. It’s just a question of time until the designation becomes official. The understatement of her forms and the silence in which they gather give her work an enchanting ephemerality.

And her forms do exist in perfect silence. They can be group swimming, dodging ocean liners or just raising hell, but they don’t utter a sound, and they have bewildering senses of personal space. In Bradford’s “Island Luncheon,” the participants are miles apart at the luncheon table, and in “Shadows,” two rump-first beach figures are in soundless duet.

I am, of course, charmed by the beauty and enigma of Bradford’s paintings. I will go on looking for answers to her work, and her work will go on telling me not to.

Fred Lynch has already become an icon. The permutative history of his work is a wonder, and the work itself can be wonderful. Lynch’s pieces in this show carry on the attitude offered in his recent show at ICON. Small, freestanding and supported by architecturally intricate frames, they continue his exploration into the division of spaces — some geometric, some organic, some near floral.

His spatial boundaries usually find their way onto sides of the works and, as often as not, onto their backs — thus forfeiting their enclosure. The work is exquisite by any measure, baffling in its ingenuity and a little troubling. I am concerned that the possibilities of infinite division may so enthrall the artist that a dilution of intensity will follow. I felt such rumblings at CMCA.

Having said all this, Lynch’s “Division Piece, #1” is a small, primarily two-sided masterpiece in black and white. An image of it is an example of what I have carried away from the show.

I’m convinced that my recollection of it will be as durable as those of the artist’s wonderful stripe paintings of years past. Their bluntness and a fluency somehow joined. Here, the work seems less intense, more lyrical.

I have written appreciatively of Mark Wethli’s small panel paintings in the past. His work in this show is of the same genre. It deals with the interplay of raw exposed linear and near-linear forms with one another; sometimes with geometric regularity, sometimes with an eccentric excursion from any mathematical rule. That adjustment harbors fascination.

I am sorry that I cannot be as fulsome about the work of Todd Watts. I am willing to ascribe my hesitation to the period from which I come. While his images are photographically achieved, they, in my eye, have the character of lithographs.

I accept the fact that photographs are no longer exclusively a product of chemistry and light, and are entitled to the title as long as something that can be likened to a camera is involved in their creation. I also accept that the maker is entitled to any liberty that he wishes to take in achieving his ends.

Nevertheless, I look for some reliance in it on the limitations of ancestry. There should be at least the smell of a camera to the product.

Still, I thought Watt’s diptych “Blue Guns and Gold” to be graphic and powerful. I also admired “A Shadow Too Many 4.” Its surrealism — light descending from some other world — is encouraged by Watts’ enormous technical skill.

The artists in the exhibition were selected by CMCA director Suzette McAvoy.

MARTHA GROOME AT ICON

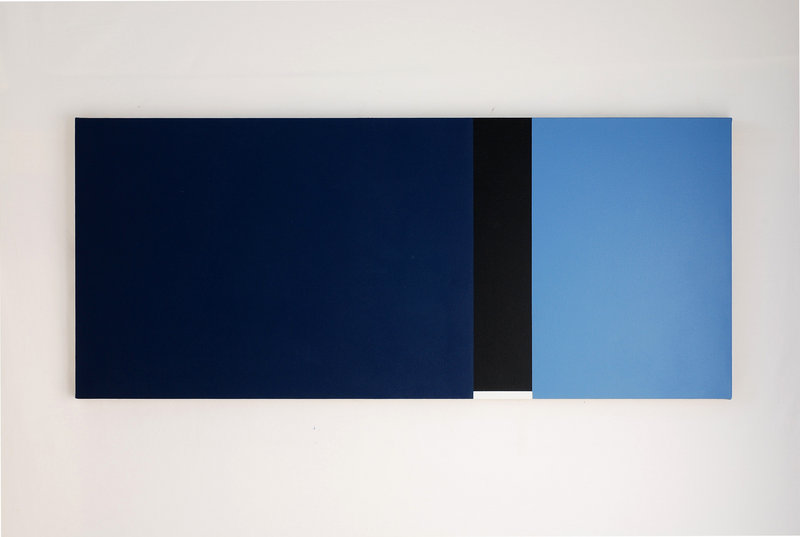

Martha Groome is the doyenne of geometric abstractionists. In her current show at ICON Contemporary Art in Brunswick, and throughout her career, she has congregated relentless horizontals and verticals into gracious equilibrium.

What that labored-over sentence means is that Groome appears to gather rectangles of various dimensions and align them with one another in a manner that exposes the dynamic force within each.

And what that explanatory sentence means is that the artist appears to treat the canvas as a surface on which to construct a collage and, in doing so, moves rectangles of moderated color around it until the canvas disappears and the resulting oppositions restrain one another.

These are fairly new considerations on my part. I had originally regarded Groome’s work as a matter of ruling the canvas into felicitous flat regions and then applying felicitous pure color. That wasn’t satisfactory, because it didn’t explain the presence of the dynamic content of the work. Lining off a canvas is passive; building on the canvas, as in a collage, adds force to the enterprise.

I note that the artist does not add boundary lines to her work; the areas in it simply touch one another. Boundary lines would support my earlier thoughts, because they propose the confinement of energy; they contain and make energy more apprehensible. Without them, the energies are free to circulate as they would in a collage.

Thus far, I have treated the paintings as two-dimensional. At ICON, I note the possible appearance of depth. This, if so, would be a radical departure.

In “Either Way,” for example, a long black passage succeeded by one in shorter white reads like a shallow channel cut through a solid gray field. In “Two Shadows,” a black channel creates a horizontal division through a white field. In both works, I sense both depth and motion. I also note “One Up”: It is exquisite in its refinement and grace.

This beautiful exhibition reminds us that formal limitations and innovation can support one another.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 47 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.