One of the semi-secret art gems in Portland is the Coleman Burke Gallery window on Congress Street. While rather small and even dingy, it inevitably contains excellent art installations.

It currently features James Marshall’s “Continuance” — 18 lead-looking paper shopping bags lined up on a plank apparently bowing under the weight. The raw plank is suspended across two ziggurat-like plinths built up of alternating and progressively narrowing steps of 2-inch-square raw wood beams.

“Continuance” is a puzzling piece. The bags were treated with Marshall’s signature myriad layers of glue and graphite until they attained a structural solidity and sculptural presence. They are fascinating objects — perplexing, perhaps, but intriguingly so.

The bend in the wood makes the table part of the installation rather than simply an element of display. The arch — an elliptical stress curve — creates extraordinary dialectical tensions with the bags. (Why are they so heavy? Is this thing a table, a pedestal or a bridge?) The mystery challenges us to unfurl the irrational against the backdrop of the mundane: Why 18 bags and 18 wooden steps?

The unspoken power of Marshall’s installation stems from the piece of furniture — that table, or whatever it is. The presence of furniture forces a sense of place defined by human purpose — whether endeavor, repose or ritual.

MECA IS HOSTING the national conference of the Furniture Society from Thursday to Saturday, so it’s not surprising there are several nearby exhibitions featuring furniture art and woodworking. Two of the most interesting include an exhibition of three Maine College of Art professors at June Fitzpatrick Gallery and then a show of MECA students past and present at Rose Contemporary, “Then & Now.”

“Then & Now” is very mixed in terms of quality, but it’s a handsome and terrifically concise introduction to issues at play in contemporary woodworking and art furniture.

Although not my favorite pieces, I particularly liked the disparate pairing of Steven Anderson’s hand-crafted red oak and coco bolo chair with Ted Lott’s “Habituation, No. 2” — a found chair over which it looks like Ken has been hard at work framing out a dream house for Barbie.

The strongest work is Vivian Beer’s “Anchored Candy No. 1,” a bench that looks something like a giant yellow woman’s pump morphing into a monolith from “2001: A Space Odyssey.” It is tight, dense, funky and intense.

My favorite, though, is Sarah Bouchard’s “White Cube,” comprising three rows of 25 standing white ladders. Each has three rungs and therefore four spatial modules. That 75 is three-quarters (think money or percent) transitively implies a fourth term which, in this case, is the whole — the gestalt. Despite its smart ironies and coolness, it’s uncannily satisfying and inclusive.

“NEW WORKS” by Matt Hutton, Jamie Johnston and Adam John Manley at June Fitzpatrick is a great show featuring nothing but highly sophisticated work by mature artists.

While 80 percent of the work is by Johnston, Hutton and Manley make significant impacts on the show. Hutton’s work is the quietest, but it forces the viewer to consider everything in the context of furniture. His three tables and a shelf are part of a project about the beautiful old Midwestern barns that are being torn down for their semi-valuable wood only to be replaced by pre-fabricated metal structures.

Hutton’s three delicately refined oval tables exude almost Roman elegance. They are defined, however, by oval boxes (that do not open) floating under the table top. It’s a haunting form — subtly funerary — that imparts the work with an unexpected sense of memorialism.

Nostalgia is, in fact, the common theme of the show.

Manley’s works all play on the idea of ships — but as toys. “Armada/Regatta” is a packed group of 2-by-4s carved elliptically to mast-like points with sails wired onto them. This group sits on a rocking base — like a crib — with clear childhood connections.

“Buoy” features a 9-foot sail-topped cedar pole bolted into a semi-spherical concrete base. Just to set this rocking is worth the trip.

Manley’s “Waterline” is a human-sized, deeply tilted wooden crow’s nest. It’s amazing for what it implies with Oldenbergian wit, from physical data to fantasy play. Manley may or may not be the son of a sailor, but these pieces will resonate with anyone who has ever visited the Admiral Benbow Inn.

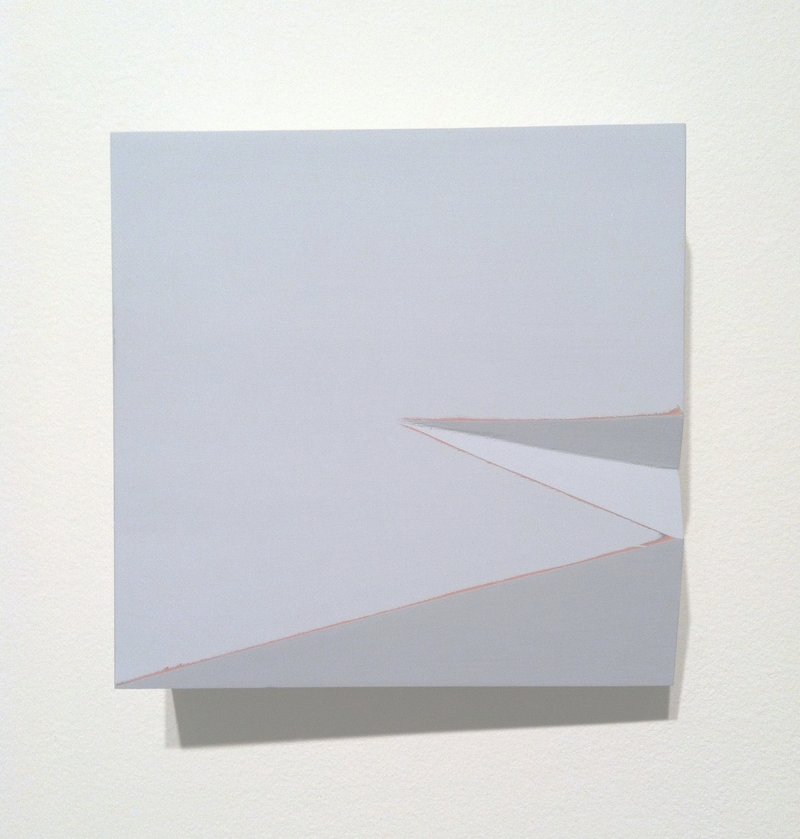

I reserve special praise for Jamie Johnston’s work, and regret not having the space here to do it justice. His wall pieces use sculptural logic, and his sculptures soar on the terms of architecture and furniture.

Most notable is the set of standing works — like a figure group — that use re-purposed table leaves. Three of the six are taller and made of darker wood, angled, jointed and painted on the edges. (It so happens that one is the leaf from Johnston’s childhood family dining table. Its edges are colored with mantis green and vermillion sign paint.) Each of the works has a unique personality, and the other two “male” pieces have geometrically fabulous gray edges that, in painterly terms, telegraph their architectural qualities.

Johnston’s fluency in furniture technique allows him to move past fussy and into the smoothly familiar textures of wear by long use. When edges are worn through, they feel natural by revealing layers past. His “paintings,” likewise, are sometimes wall objects with script so covered by layers of finish that they are only visible to the extent of the depth of their carved marks. His metaphorical deployment of mark and memory is brilliant. It’s unrecoverably subtle but wonderful nonetheless.

Furniture-related art often now addresses some of the most complex conceptual real estate of contemporary art, because it touches so many cultural boundaries with integrity rather than deflected irony.

I hardly scratched the surface of Johnston’s work here, but, like everything in this review, it’s best seen in person.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.