While many Americans are riveted by the Penn State sex abuse trial, it has been particularly wrenching — and sometimes heartening — for those who were themselves victims of abuse in their youth.

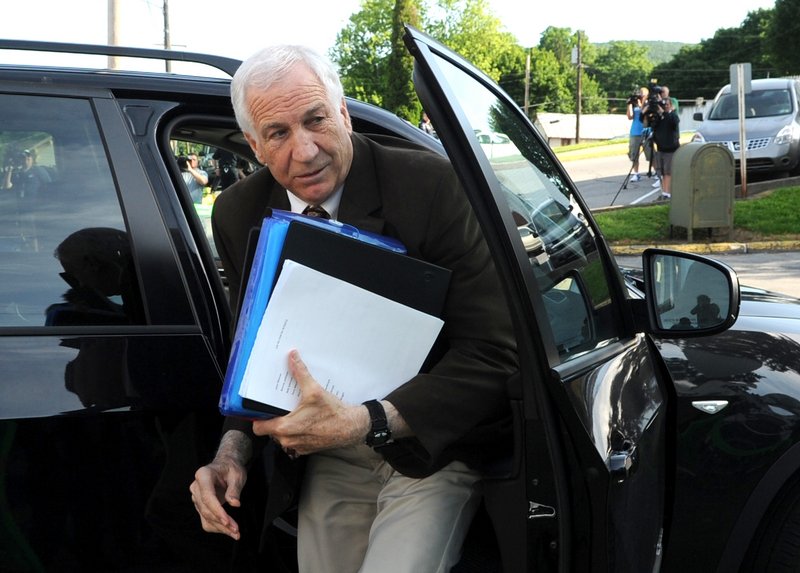

Unlike the witnesses testifying against Jerry Sandusky, most of them never got the chance to confront their abusers in court, so the trial has been cathartic as well as troubling.

“It’s vicarious justice — the closest many survivors will ever get to a courtroom where the perpetrator is held accountable,” said Claudia Vercellotti of Toledo, Ohio, who says she was molested for years in her adolescence by a Roman Catholic youth minister.

Vercellotti, a 42-year-old hospital employee, has immersed herself in news reports of the past week’s often-graphic testimony from eight young men who said Sandusky, a former Penn State assistant football coach, had abused them.

“It takes raw courage to get up there and face their abuser,” she said. “They are liberating other victims of sex crimes who have not been able to speak up. There are people across this country saying, ‘Me, too. Me, too.’ “

Vercellotti and others who were interviewed clearly believe Sandusky is guilty. But to them, the testimony in a Bellefonte, Pa., courtroom is not just about allegations that one man assaulted boys; it also shines a spotlight on all abuse, including their own. And painful as it is, some say this can only be a good thing.

“Once you accept the notion that child sex abuse is stunningly widespread, then every instance in which it emerges into the public consciousness is essentially good — painful but good,” said David Clohessy, the St. Louis-based executive director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. “Kids are safer, and victims move further toward recovery.”

Clohessy, who says he was abused by a priest while in his teens, expressed admiration for the witnesses testifying against Sandusky and standing up to cross-examination.

“It’s one thing to deal with horrific pain privately … and perhaps toughest of all to deal with it in a public, adversarial setting,” he said. “They’ve moved from a therapist’s couch to what’s essentially a battleground.”

Among the vast number of sex abuse cases, the Sandusky trial is relatively unusual in providing a direct courtroom confrontation between alleged victims and their alleged abuser. Victims often wait many years before speaking out, and often no trial takes place because the alleged abuser is dead or the statute of limitations precludes prosecution.

That was the case for John Pilmaier, a 41-year-old social worker in Milwaukee. He says he was abused by a priest while in second grade at a Catholic school in Brookfield, Wis., but told no one about it until he was 36. He reached a financial settlement with the Milwaukee Archdiocese, he said, but was prevented by Wisconsin’s statute of limitations from taking the priest to court.

Pilmaier has gained some vicarious satisfaction as he follows the Sandusky testimony.

“It’s heartening for me to see them testify and hold the person accountable — a lot of us weren’t able to do that,” Pilmaier said.

“That can be a very healing thing — to be able to stare down the person who so grievously harmed you,” he said. “It’s what you couldn’t do as a child. You’re able to take power back from the abuser.”

Becky Ianni of Burke, Va., waited until she was 48 to reveal abuse she says she endured at the hands of a priest when she was 9 and 10.

When she decided to speak out, in 2006, she went before a church review board to make her allegations, and burst into tears as she underwent questioning. She said memories of that encounter resurfaced as she followed the reports of some of the Sandusky witnesses fighting back tears during their testimony.

“I remembered sobbing and crying when I went to the church and told my story … and being challenged about it,” she said. “To me, it felt like I was on trial. I remember how hard it was for me, and how ashamed I felt about what happened to me. My heart went out to these victims, thinking how hard it must be for them.”

Ianni admitted to a trace of envy that the witnesses have a chance to confront Sandusky. “My perpetrator committed suicide in 1992,” she said. “I had no chance to confront him.”

Not all abuse survivors are following every twist and turn of the trial. Deborah Donovan Rice of Stop It Now, an abuse-prevention organization based in Northampton, Mass., says she reads the headlines and skims the articles, but purposefully avoids the graphic details.

“It’s self-protection,” said Rice, who says she was abused as a girl by a child-care worker. “I’ve lived that story. Going into the details would pull me into a zone of being awash in emotions. It would be disempowering.”

By contrast, Al Chesley, a former pro football player, attended one of the trial sessions, and has been speaking out about parallels between the Sandusky case and his own story of being abused by a police officer as a youth in Washington, D.C.

Chesley, 54, who played linebacker for the Philadelphia Eagles and Chicago Bears, didn’t talk about being abused until 2008. He has since become a children’s rights advocate.

Another abuse survivor who traveled to Bellefonte for the trial was lawyer Jeff Dion, the deputy executive director of the National Center for Victims of Crime. He expressed empathy with the accusers, suggesting that most of them would have preferred to avoid having to recount their experiences in public.

“I’m so glad that’s not me having to testify, because the shame and humiliation is so strong,” he said. “Survivors everywhere find themselves rooting for these victims … If they are validated and vindicated, it’s in many ways a vindication for victims everywhere.”oach must make himself available for prosecutors so they can prepare rebuttal psychiatric testimony.

The American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual calls histrionic personality disorder “a pervasive pattern of excessive emotionality and attention seeking” and “often characterized by inappropriate sexually seductive or provocative behavior” and rapidly shifting emotions.

The defense motion said people with the condition would not necessarily be grooming boys to molest them but instead might be trying to “satisfy the needs of a psyche” with the disorder.

“The jury should not be misled into believing these statements and actions are likely grooming when they are just as likely or more likely histrionic in origin,” wrote defense attorney Karl Rominger in the June 11 filing.

Testimony in the 68-year-old former coach’s criminal trial is expected to resume Monday.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.