Nancy Meader’s pots have an organic feel that revels in their maker’s hands. On her tall vases, her thumbprints run up and down the outer seam. Her “People Pots” are loose and varied. With a head, neck and body, they have that recognizable regularity that makes them human but enough individuality to make them people. A group of them in the corner of the Harlow Gallery, for example, looks like family.

Nancy’s landscape pots feel like Marsden Hartley paintings in sculptural clay. Their mountainous top edges play off each other. A simple sun in the sky gives the whole thing life and warmth. And while the forms are stylized, they never lose the feel of the artist’s hand. They seem humble but they are smart, loose, well-designed and well-executed.

Nancy’s ceramics are raku — low-fired outdoors with a portable kiln. They are finished with reduction processes that make the copper glazed pieces iridescent: In reflected light, their metallic sheen is shiftingly prismatic. About half, however, have crazed (crackled) surfaces. The reduction firing fills the lines (made by blowing on the pots when they are glowing hot) with black carbon.

Abbott Meader’s landscape drawings are not traditional in the sense of art history, but they fit perfectly with the American mythos about the artist realizing and translating his view of the world through his hand. They are colorfully spirited images of intimate spaces in the Maine woods that blend spiritual presence with energized enthusiasm.

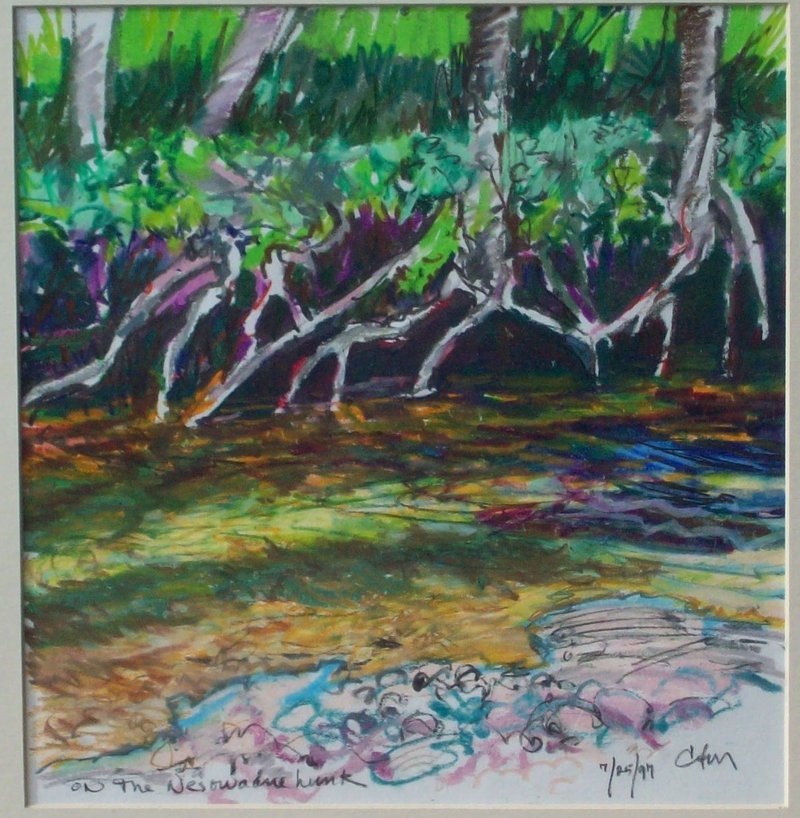

Abbott’s “On the Nesowadnehunk” (1997) shows an undercut bank up close. Four gray trunks shoot up through three layers of green growth at the top of the image. Below is a layer where their exposed roots reach down through purple-dark space toward the water — orange and maroon in the shadows and greened yellows where the sunlight reflects up off the stony shallow bend in the stream bed.

The striated logic continues throughout the piece with the near shore depicted by a wonderful set of scribbled light blue and periwinkle marks set among the bold and script-like pencil depicting the pebble beach.

Rather than some eternal portrait, this piece is more like a snapshot of a memorable encounter. But it is handled with the artistic presence of Abstract Expressionism (spiritual) or even Richard Diebenkorn (structural).

It’s rare to see a husband and wife art show that really works, but “Streams, Stones and Frozen Fire” succeeds brilliantly.

The two-person show comprises Abbott’s framed landscapes on paper on the walls with Nancy’s raku pots on low pedestals flowing throughout the gallery. It’s a large show with about 40 landscapes and a similar number of Nancy’s ceramics.

Abbott has never mounted anything like this show of his work. It’s a coherent body of plein air landscape drawings mostly in oil pastel and pencil. They are all framed works on paper and range from the last 25 years.

It’s a very strong body of work — strong enough to make anyone who doesn’t know Abbott’s paintings, films, collages, et cetera, believe this is who Abbott Meader really is as an artist. It’s an extremely appealing idea because there is something very personal about drawing. Maybe this is the real Abbott Meader standing up.

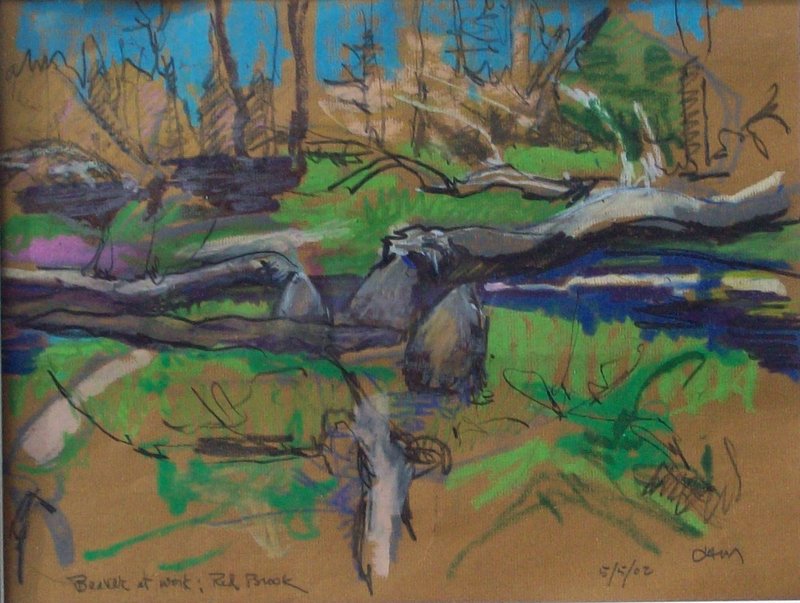

My favorite piece, “Beaver at Work,” leaves much of the brown paper revealed. There is a complex form of a downed tree that wells up from the bottom center of the image and then visually flows off to each side. The beaver (which wouldn’t be recognizable if not for the title) is working quietly, well away from the unobtrusive artist. While the drawing marks are impressive, it is the satisfying and sophisticated complexity of the composition that makes this piece great.

Abbott’s work has always maintained an artistic vision that runs deep with a nature-worshipping spirituality that, at times, is even mystical. Yet Abbott’s pictures exude an urgency that makes a clarion call for the here-and-now. You can see in these drawings that he was racing to gather his observations of a specific space/time moment that included light, shadows, clouds, beams of light and visible currents in a stream. Abbott’s nature is alive and dynamic. It is organic, colorful and energized.

I think oil pastels are an under-valued medium. They are small paint sticks, but since kids can use them, we tend to look down our noses at them. (I think the similar attitude about watercolor is practically tragic: After all, this is the place of Homer, Marin, the Wyeths and scores of great artists associated with watercolor.)

But with oil pastels, to draw is to paint — and vice versa. This means we can see energetic gestures, the hand of the artist, draftsmanship, contour and color. The medium allows Abbott to work quickly on site and then return to the piece later to finish it with an eye to taking it from first-person experiential observation toward a strong work of art from the viewer’s perspective. It’s clear from these drawings that Abbott is critical of his own work. Fortunately for us, however, he knows when to leave well-enough alone.

“Streams, Stones and Frozen Fire” is a fantastic show.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at: dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.