Other than Colby’s paean in perpetuity to Alex Katz, no major living artist’s work can be more broadly seen in Maine than that of Lois Dodd.

I don’t have statistical support for that carefully hedged declaration, but I believe it devoutly. Lois Dodd has a stream of thoughts about how we look and, for an artist of her distinction, is remarkably generous about making them available. Her paintings are a feature of art about Maine and seem to appear almost spontaneously.

What’s all that got to do with the price of apples? Well, the frequency and nonchalance of her gallery venues are a physical expression of the nonchalance that I find in her art. As shrewd as her eye is — she can separate the instantaneous impulse from its longer-lived cousins — she offers it with the casualness of a painter asking for but a moment of your time. It’s a terrible risk, and I can think of no other painter of her stature willing to take it.

Usually I expect a display of some insistent variety of brilliance — technique, philosophical insight, shock, etc. — something that will demand your attention. In Dodd’s case, the brilliance is in quickly noting the moment and endowing it with the energy to preserve it. Her work has a circular form of perpetual motion; she finds the moment, allows it to move along and then recaptures it. It’s magic.

The sources of that magic lie in the freedom that gestural painting has granted her and in the fact that she paints plein air. Gesture enables speed, and plein air requires it.

You can interpret that sentence at Dodd’s current show at Caldbeck in Rockland. Look for “Moonlight on Incoming Tide, September,” a postcard-sized painting on a piece of aluminum. In it are night, clouds, water, the moon and a ladder. Everything is pushed by the forces of nature. Those forces exclude it from being a leisurely nocturne; rather, they speak of motion and the artist’s urgency to depict it. There are flowers, raindrops, evening clouds and spooky houses on dark roads in this jewel of a show.

Dodd is not alone at Caldbeck. The principal galleries are given over to work by Stew Henderson and by John D. Woolsey.

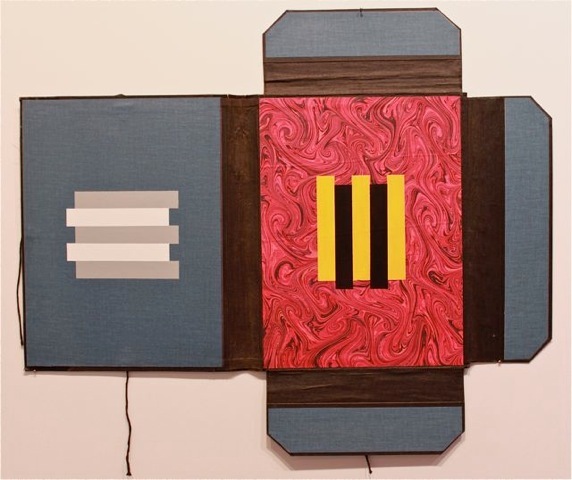

Henderson’s work is gathered under the title “Distilled Concrete.” My weakness in art history popped up when I concluded that “Concrete” meant concrete. It doesn’t. Henderson, in an Artist’s Statement, advises that it is a term applied to a group of Western European art made during the early 20th century. It fits under the umbrella of abstract art; unlike the pack, however, it removes any social or political content, but works to remain relevant and even useful to society at large.

I offer no further information about the original group, but assure you that Henderson’s handsome distillations on the walls at Caldbeck are entirely relevant to today. They strike me as further contributions to the revival of geometric abstraction, a noble and severely demanding approach to beauty.

I see in Henderson’s work the aesthetic satisfactions of logic, lineal harmony, precision and animation. The latter, animation, is not a common component of the type, but this artist breaks from the mold with shaped canvasses and an interplay of colors. Some of the larger pieces are right triangles — a form that implies motion — and, as I recall, all of the works offer linear repetitions in limited colors that give them a beat encouraged a bit by the effect of a keyboard.

My favorite is “German Suite,” a group of small wood-embraced linear work contrapunctually arranged and pulsing with black and silver. It could have hung at the Bauhaus if it had been born two generations earlier.

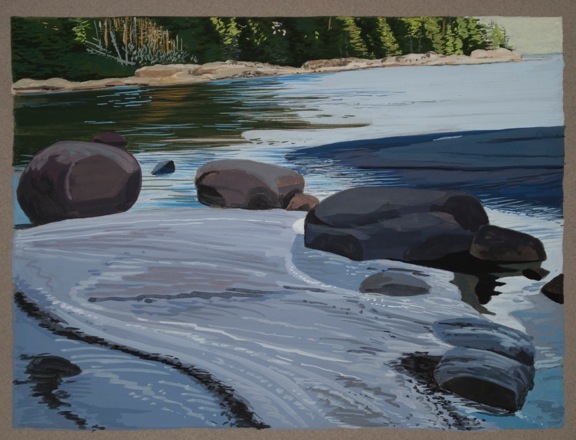

John D. Woolsey’s paintings are grouped as “Musing on the Relativity of Time.” The concept is too challenging for me, but the work is distinguished for an embrace of the coast that shifts from voluptuous to respectful. The first tends to be in gouache on paper and small in scale. The respectful works are accomplished in pastel on paper and present a glacier-scrubbed area (which I take to be at or near Brooksville) as rough-shelled and unyielding. These are in significantly larger scale.

The gouaches are more summary, but with their blended strokes they capture the moment with such fluidity that I found them enchanting. I mention “Erratics on Ledge, McGlathery Island” and “Late Light on Ledge” in this group.

“Ledge and Small Island,” McGlathery Island” is one of the principal images among the pastels. The weight of its glacier-age ancestry will keep it durable.

SHOW LOOKS AT ARTISTRY IN BOOKS

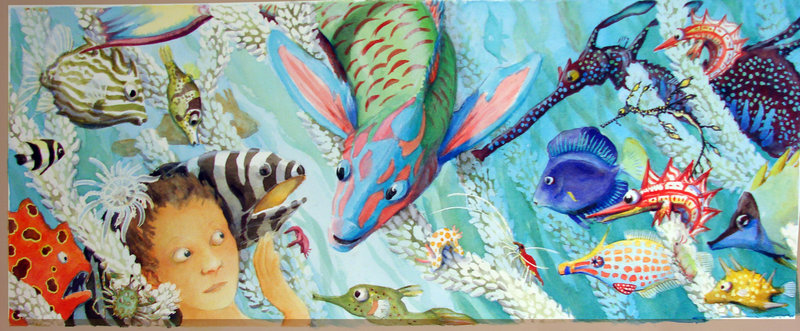

A show for all ages is as scarce as hen’s teeth. I’m not certain whether there are hens in a show that I’ve just seen, but there are plenty of other fowl among the creatures that occupy its galleries. The event is called “Tell Me a Story: A World of Wonders” and treats children’s book illustrations on science-related themes.

Organized and presented by the Atrium Art Gallery at USM, Lewiston-Auburn College, it gathers work by 11 Maine artists commissioned for books for young readers from preschool and on. The lure, of course, is the charm of the works’ intentions, viz, the intrinsic beauty of the creatures in their given habitats presented explicitly and with sympathy.

The images make their point, and take advantage of the visual opportunities and the fanciful conjunctions that the genre allows. Fish gotta swim, but they can enjoy themselves in the process. In other words, it’s a beautiful show.

The particular pleasure for older eyes is the fact that you are looking at the watercolors, pastels and collages from which the book printers worked. Some are technical marvels in themselves, and translating them into print must have turned those technicians into artists of another kind.

The works in this show are achievements that never get seen. After they leave the hands of the printer, they go into a long, wistful seclusion. This adds to the allure of the event.

Selecting at random, I note “Everybody Is Somebody’s Lunch,” a watercolor by Gustave Moore. His peaceable kingdom is a prelude to an essay on the balance of nature and the recognition that, in nature, it’s not a question of the good versus the bad. It’s a hard lesson to learn.

Olga Pastuchiv’s “Minas and the Fish” is a spooky ride on a magical fish. It would have made my grandchildren scream, with the pleasure blunted with fear.

Jim Soller’s watercolor “Beau Beaver Goes to Town” is a lesson in urban detritus and its casual disposal.

I was charmed by the elegance and precision of “Mermaid in a Tidal Pool” by Mimi Gregoire Carpenter. It’s a guide to the overlooked on the way to water’s edge.

This show, like so much at the atrium, deals with the overlooked of Maine aesthetic abundance.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 47 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.