CLEVELAND – John Wise watched a tear roll down his wife’s face as he stood alongside her bed in the intensive care unit. She’d been unable to speak after suffering a stroke and seemed to be blinking to acknowledge him, Wise confided to a friend who had driven him to the hospital.

The couple had been married 45 years and Wise told his friend that they had agreed long ago they didn’t want to live out their years bedridden and disabled.

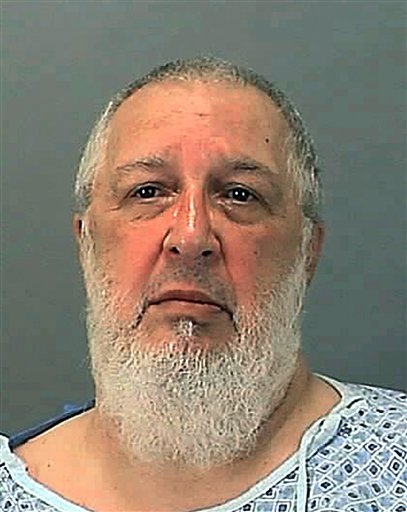

So a week after Barbara Wise’s stroke, investigators say, her husband fired a single round into her head. She died the next day, leading prosecutors to charge the 66-year-old man with aggravated murder Wednesday in what police suspect was a mercy killing.

The shooting leaves authorities in a dilemma that some experts say will happen with greater frequency as the baby boom generation ages — what is the appropriate punishment when a relative kills a loved one to end their suffering?

More often than not, a husband who kills an ailing wife never goes to trial and lands a plea deal with a sentence that carries no more than a few years in prison, research has shown. In some instances, there are no charges.

“It’s a tragedy all around that the law really isn’t designed to address,” said Mike Benza, who teaches law at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

A Brentwood, N.Y., man in March was sentenced to six months in jail after suffocating his 98-year-old disabled mother and slitting his own wrists. Juan Gonzalez, 70, told authorities he had just been told he had skin cancer and believed he was going to die soon, and feared no one would care for his mom.

Donald Neely, 54, of Bothell, Wash., accused of shooting his terminally ill 52-year-old wife this year, told investigators she had begged him to kill her; he is free on bail while prosecutors weigh charges.

Almost always, there are deeper issues involved with the accused, including depression, their own health problems and the stress of taking care of a dying spouse, said Donna Cohen, head of the Violence and Injury Prevention Program at the University of South Florida.

Seeing a dying or disabled spouse suffering can be enough to push someone over the edge, said Cohen, who is writing a book called “Caregivers Who Kill.”

She worries this will happen more often with longer life expectancies and a continuing shortage of mental health services for older people.

In the early 2000s, testifying before a Florida legislative committee, Cohen cited research showing that two in five homicide-suicides in the state involved people 55 and older. The number of cases grew among older people while staying the same with those under 55.

Wise’s lawyer has said that he was a good man who was devoted to his wife.

The former welder also suffered from nerve damage that made his hands and feet numb, survived bladder cancer and had diabetes, said Terry Henderson, a 30-year steel plant co-worker.

Those issues could help his case if it goes to trial. “The facts surrounding her death are sympathetic and may actually foster a plea before trial,” said Jeff Laybourne, a prominent Akron defense attorney.

But just because his wife may have been suffering isn’t a valid defense under the law, Laybourne said.

Other factors that could determine whether the case goes to trial include the timing of the shooting and that it happened in such a public place.

Henderson thinks Wise may have snapped under the weight of both of their health concerns. “He never dreamed, given his history of medical problems, that this would happen to her before he’d go,” Henderson said.

That kind of situation can be deeply depressing for a person dependent on the care of a spouse who suddenly is disabled, said Dr. Peter DeGolia, a physician specializing in care for the aging at University Hospitals Case Medical Center in Cleveland.

“If this man was dependent on his wife for care and basic well-being, and suddenly she’s gone, he’s going to feel very vulnerable, highly at risk,” he said. “Older white males are the highest risk group for carrying out suicide plans.”

It’s a scenario that DeGolia said can be defused with help from social workers and hospice care for the dying.

“There are lots of options,” he said, “aside from going and shooting them.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.