In a characteristically chatty letter from Paris to her sister-in-law, Freddie, Julia Child expresses curiosity about a “newfangled sensation” called television. “How much do you really use it? . . . How do you like the programs? . . . My heavens, I am beginning to feel very out-of-date indeed.”

It was 1952. Television was a novelty, and Child was debating the wisdom of collaborating with her new friend Simone Beck on the cookbook that would become “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.” No one, least of all Child, could have predicted she’d become food TV’s first superstar.

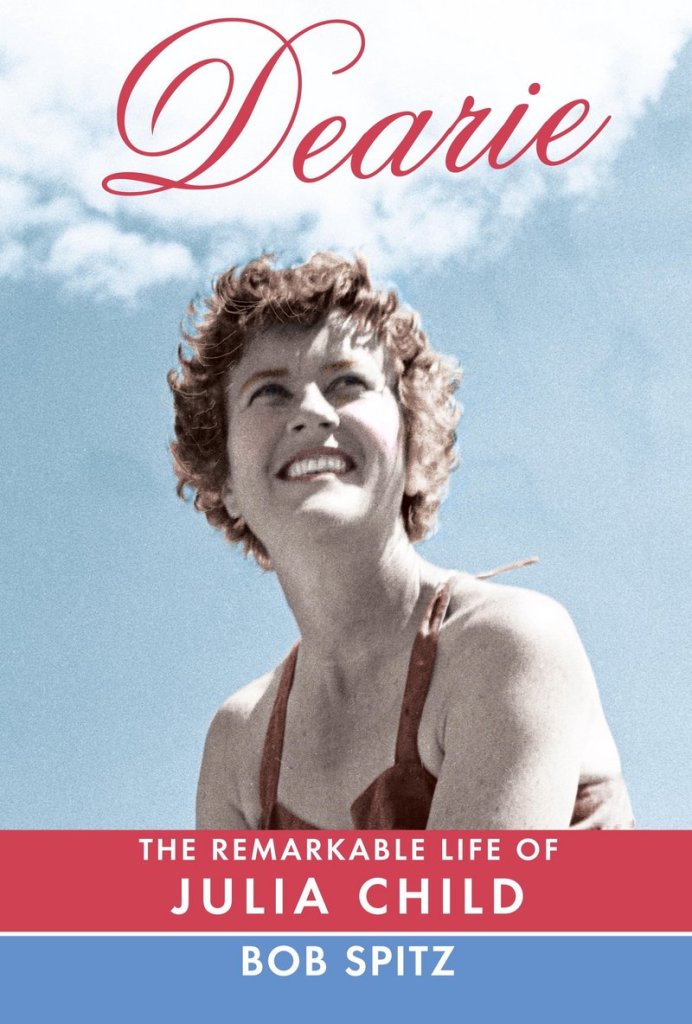

There are plenty of deliciously ironic moments like this one in “Dearie,” Bob Spitz’s detailed and broadly contextual new biography of Child, which debuts in time for her 100th birthday. After “Julie and Julia” (book and movie), “As Always” (a compilation of Child’s letters to friend and literary agent Avis DeVoto) and Child’s own posthumously published memoir, “My Life in France,” a nearly 600-page hagiography might seem like overkill.

But “Dearie” has much to add to these personal accounts. A consideration not only of her life but of her place in 20th century American history, the book makes a strong case for Child as a “cultural guerrilla” on par with Andy Warhol, Bob Dylan and Helen Gurley Brown.

Born into a wealthy family in Pasadena, Calif., Julia could have followed a conventional path, marrying well and pursuing the country club lifestyle to which she was destined. But natural restlessness and a wild streak prevented her from settling down.

“A grand person generally, but she does go berserk every once in a while,” wrote her Smith College housemother. After graduation, Child cast about for meaningful work in publishing and merchandising, finding time to swill martinis with the smart set. The war provided her with a reason to travel. She joined the OSS (a predecessor to the CIA) and spent almost a year in Ceylon, contributing to the intelligence effort.

In Ceylon she met Paul Child, a career diplomat and frustrated artist who became her biggest supporter. After their marriage, a felicitous posting in postwar Paris ultimately led her to the classrooms of the Cordon Bleu. Along with a bunch of tough-talking American GIs, Julia learned to prep vegetables and make sauces.

Immediately, she was captivated, rushing home from school every day to practice. In the first six weeks alone, she served rabbit terrine, quiche Lorraine, vol-au-vent, duck a l’orange and much more to her stunned husband. Finally, she had found an occupation that satisfied her intellectual curiosity and boundless hunger.

It also brought out her latent perfectionism. In an attempt to understand mayonnaise, she made dozens of batches, experimenting with temperature, moisture, energy and time; these trials would become a template for her later work.

In 1951, she met Beck. The two toiled away on “Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” even after it was rejected, revising recipes and rewriting several times before it finally came out with Alfred A. Knopf in 1961.

The same perfectionism marked her television debut on the “Today” show to promote the book. The night before her appearance, she went through five dozen eggs, choreographing the cooking of an omelet to fit into a two-minute time slot. When “The French Chef” premiered on public television in 1962, it was an instant sensation.

Child’s apparent spontaneity was part of her appeal. In reality, she left very little to chance. Of the first three pilot episodes, she explained, “I knew my lines, and Paul had mapped out a master plan, like an Arthur Murray dance diagram.”

Her drive and professionalism were key to her cultural importance: “Julia tapped into a housewife’s desire to expand the boundaries of her own world,” writes Spitz. “Nobody knew American women were out there hungering for this, but out there they were. And Julia offered them an outlet for that pent-up ambition.”

Spitz gives us plenty of the wacky one-liners that endeared Child to her television audience, and a warm, nuanced portrait. But his bigger achievement is in setting her career against the most significant movements of the 20th century, from McCarthyism to the sexual revolution to the greening of America. He reveals how she helped redefine domesticity in the media age, transforming the way we cook, eat and think about food.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.