“Two of the most remarkable aspects of the maritime war of 1812 were the extraordinarily high casualty rate among officers on both sides of the conflict and the mass of recorded anecdotal evidence pointing toward an equally high incidence of magnanimous behavior on the part of the same officers toward their opposite numbers in the British and American navies.”

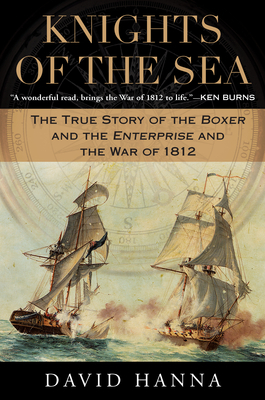

So observes historian and teacher David Hanna in his stirring new book, “Knights of the Sea: The True Story of the Boxer and the Enterprise and the War of 1812.”

Indeed, what Maine-born historian Alan Taylor has termed (for other reasons) “the Civil War of 1812” was also a war of high civility within the upper echelons of the armed services.

Civility amid appalling carnage — as well as the wish for noble conquest or glorious death — may be Hanna’s chief interest, but he does not stint on any other parts of Maine’s most memorable sea fight.

“Knights of the Sea” is the finest overall account of the vessels; the captains; the short, horrific battle; and its meaning since Sherwood Picking’s classic “Sea Fight Off Monhegan” (Portland, 1941).

Hanna’s great advantage has been to build on Picking and subsequent documentation steeped in the novels and serious researches of C.S. Forester and Patrick O’Brien. Few writers have understood life and work in the late 18th- and early 19th-century better. They were able to make it come alive in spell-binding stories.

Clearly, they inspire Hanna, and he occasionally quotes them. But he clearly knows their facts from their fictions. If anything, the documented truths about Boxer and Enterprise — and the commanders and their missions — only bolster the authority of the literary crew.

In a compact, well-organized and carefully illustrated book, Hanna propels the reader both general and scholarly with sure, swift and colorful prose: “A member of one of the Enterprise’s gun crews by the name of Jordan grew so impatient at the rate of fire that he used his own forearms to ram the shot home before it was discharged!”

Hanna ventures from Portsmouth, England: The great naval town that produced Boxer’s future captain, Samuel Blyth, to Philadelphia, the hometown of the future Enterprise commander, William Burrows. Both captains were born to sea-faring families.

He discusses the histories of the Boxer and Enterprise, and goes on to deal with the attitude and outlook of naval officers in the era.

All this is nicely handled, and I think there is little to argue with regarding Hanna’s thesis: “What Burrows and Blyth were fighting about was less important than the fact that they were fighting.”

On Sept. 5, 1813, Blyth was being paid by American merchants to escort a smuggler into the Kennebec River, and their feigned exchange of gunshots brought Burrows into action.

The Brits, though slightly less powerful, had no honorable choice but to challenge and fire the first shot. Enterprise fired the second, blowing Capt. Blyth in two. While Enterprise gained the weather gauge, Capt. Burrows was mortally wounded. The Boxer was decimated.

All this was heard or seen through smoke by folks at Pemaquid, and the Boxer, with some 50 casualties, was towed to Portland by the American vessel, with three men killed and 14 wounded.

It was a welcome victory, but with both captains killed, a somber show was made. They were buried together in Eastern Cemetery, and remembered in Longfellow’s verse and in subsequent joint naval memorials.

Hanna brings it all together with dignity and skill.

William David Barry is a Portland historian who has authored or co-authored several books, including “Maine: The Wilder Half of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.