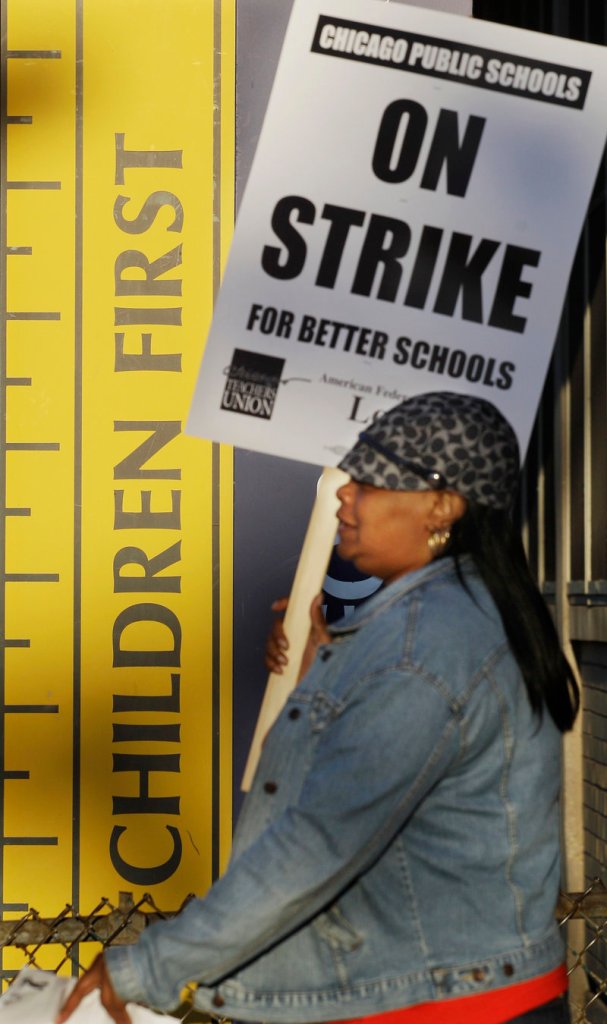

CHICAGO — For the first time in a quarter century, Chicago teachers walked out of the classroom Monday, taking a bitter contract dispute over evaluations and job security to the streets of the nation’s third-largest city less than a week after most schools opened for fall.

The walkout forced hundreds of thousands of parents to scramble for a place to send idle children and created an unwelcome political distraction for Mayor Rahm Emanuel.

In a year when labor unions have been losing ground nationwide, the implications were sure to extend far beyond Chicago, particularly for districts engaged in similar debates.

“This is a long-term battle that everyone’s going to watch,” said Eric Hanuskek, a senior fellow in education at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University. “Other teachers unions in the United States are wondering if they should follow suit.”

The union had vowed to strike Monday if there was no agreement on a new contract, even though the district had offered a 16 percent raise over four years and the two sides had essentially agreed on a longer school day.

With an average annual salary of $76,000, Chicago teachers are among the highest-paid in the nation, according to the National Council on Teacher Quality.

But negotiators were still divided on job security measures and a system for evaluating teachers that hinged in part on students’ standardized test scores.

The strike in a district where the vast majority of students are poor and minority put Chicago at the epicenter of a struggle between big cities and teachers unions for control of schools.

Emanuel, who has sought major reforms while also confronting the district’s $700 million budget shortfall, acknowledged his own fight with the union, even as he urged a quick resolution.

“Don’t take it out on the kids of Chicago if you have a problem with me,” he told reporters Monday.

As negotiators resumed talks, thousands of teachers and their supporters took over several downtown streets during the Monday evening rush.

Police secured several blocks around district headquarters as the crowds marched and chanted.

The protesters planned to rally through the evening at an event that resembled a family street fair. Balloons, American flags and homemade signs hung above the crowd.

Teacher Kimberly Crawford said she was most concerned about issues such as class size and the lack of air conditioning.

“It’s not just about the raise,” she said. “I’ve worked without a raise for two years.”

The strike quickly became part of the presidential campaign. Republican candidate Mitt Romney said teachers were turning their backs on students. President Obama’s top spokesman said the president has not taken sides but is urging both the sides to settle quickly.

Emanuel, who just agreed to take a larger role in fundraising for Obama’s re-election, dismissed Romney’s comments as “lip service.”

But one labor expert said that a major strike unfolding in the shadow of the November election could only hurt a president who desperately needs the votes of workers, including teachers, in battleground states.

“I can’t imagine this is good for the president and something he can afford to have go on for more than a week,” said Robert Bruno, a professor of labor and employment relations at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.