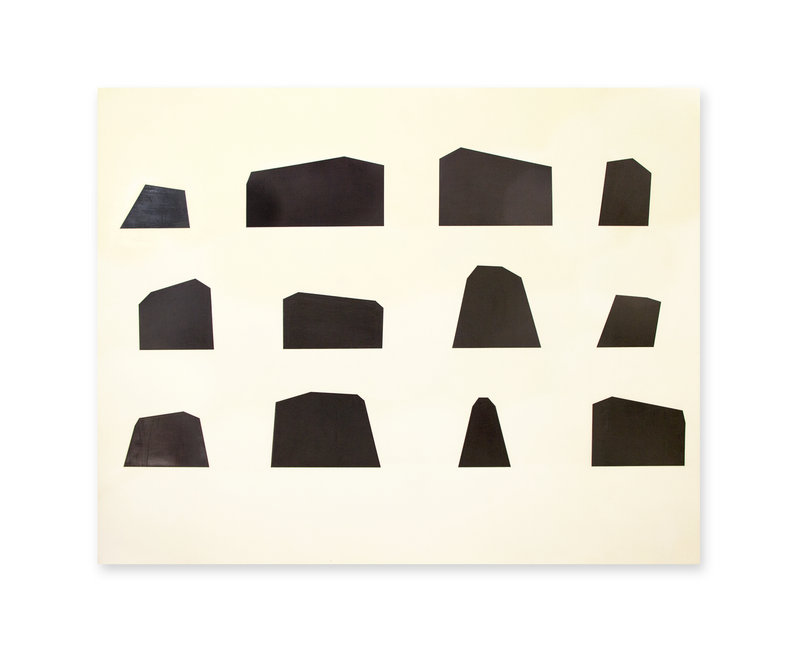

Jeff Kellar works on the severe edge of geometric abstraction. On first impression, his pieces are so chaste that thoughts about sensual qualities are a concealed form of leering. They seem so plotted, so engineered, so exquisitely achieved, that any potential for sensory delight has been squeezed out of them.

His pieces appear to sit as skeptical observers of the immoderate world of forms and colors squirming around them.

I have collected these high-flown thoughts over a period of many years — in fact, since the days when Kellar was a furniture maker. Back then, his case pieces had the intellectualized and engineered finesse of one of the leading forms of modernism. Purity of line and craftsmanship were the thing; in fact, you couldn’t have one without the other.

I see my memories embedded in much of Kellar’s fine art in “Prospect,” his current show at ICON Contemporary Art in Brunswick.

Called wall pieces, his two-dimensional works are intellectualized, engineered to within an inch of their lives and so brilliantly achieved that, at first view, the works are paeans to chastity.

The dignity of the work at ICON urges this conclusion, but the generosity of a one-person show — its amplitude — forestalls quick judgment. It gives us a second chance to look and think chastity over.

Ultimately, Kellar emerges less as ascetic than I have held and more as a poetic contemplative. I’ve cobbled that term together to suggest that there is a tempo of repetition within his pieces that can be extracted on quiet effort.

There is movement in the application of the materials in the pieces — resin, clay, pigment applied to aluminum panels. His art can be read as a compilation of distinct rectangular forms that work against one another, sometimes through shifts in elevation, sometimes through shifts in color or proportion.

These factors may combine to make a piece oscillate as in “Wall Drawing 24,” or more so in “Glimpse (Night).” They can, in my aesthetic closet, suggest the fantasy that I suspect lurks in certain forms of geometric abstraction. It is not easy to extract fantasy from Kellar’s austerity, but it gives the pieces emotional energy.

And finally, as a modification of the initial resoluteness of his work, I see Kellar’s fastidious craftsmanship. It becomes a component in the poetry. Generally, I avoid excursions into craftsmanship — a subject that I know particularly little about — but Kellar has raised it to a high element in his art.

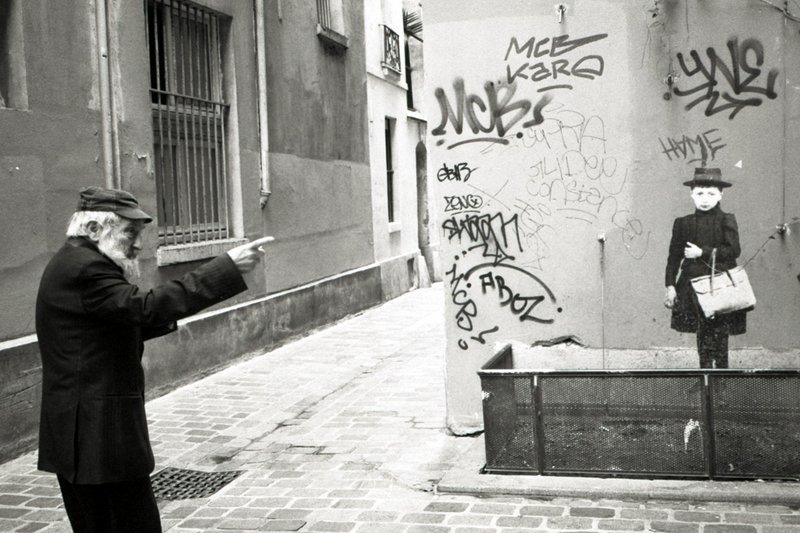

IT IS A PLEASURE to review the work of Ruth Sylmor. It often has to do with Paris, a city that she loves, knows well and photographs with an eye for its curious anomalies. If I knew Paris better, it’s unlikely that I would find Sylmor’s forages an embrace of the anomalous. Paris is probably cooler than I realize.

Her subject is street art going back to the 1980s. Another term for it is graffiti. That it endures in Paris — a city that thinks particularly well of itself — surprises me.

I am not surprised that it is produced, but the fact that the authorities have quietly tolerated it for so long is unexpected.

Sylmor’s show at Addison Woolley Gallery, “Paris Walls re/con/figured,” deals with the lessening of that tolerance. As an artist drawn to street photography, the subversiveness and graphic value of street art hold her attention.

In the 1980s, Paris embraced a generation of street artists who were largely skilled in the use of large stencils. They attacked the establishment, shunned museums and thumbed their noses at highbrows. They climbed the ladders at night, avoided the police and flourished in unexpected places.

In time, some among them rose to prominence. Although their images were intended to be impermanent, the most gripping works became icons and their makers became celebrities. In fact, some of their images were, in time, commissioned.

Now time, weather and the lessening of official tolerance threaten even the most established images. For years, Sylmor has tracked the celebrities and their work — negotiating, as she has said, the space between the real world in which the images exist and the world of fantasy that they imply.

Sylmor’s images in this show are graphic. All in black and white, they embrace both worlds and join them with the activity of the streets around them. She works very much in the tradition of the instant eye at the perfect moment, and calls to mind Cartier-Bresson. Her photographs are a presentation of form and vitality offered with love.

DISCOVERING “MAINE’S WOODS” at the Atrium Art Gallery at Lewiston-Auburn College (or, more accurately, being directed there by Bruce Brown) warmed the cockles of my heart. The event is an absolute delight. Offered for both the rich beauty of its images and their historical association, it is not burdened by art-historical thoughts or duties. Plus, a good story goes with it.

First, the story. A gentleman by the name of Bert L. Call was a portrait photographer in Dexter from 1886 until the late 1940s. He was also an inveterate explorer of the woods, waterways and mountains of northern Maine.

Beginning some 120 years ago (only 30 years after Thoreau), Call began the process of recording events and impressions along his journeys. Considering the times, hauling photo equipment along with camping gear was a significant undertaking.

After his death, Call’s images in both negative and print form made their way to the Dexter Historical Society where, until recently, they have had limited public attention.

“Maine Woods” enlarges the public’s opportunity to appraise Call’s efforts and to see images of a part of Maine that in many cases were, to Call, unchanged since the journeys of Thoreau.

I don’t want to put too fine a point on this. The images are matched to quotes from Thoreau’s “The Maine Woods,” but there are things or instances that Thoreau could not have seen — for example, a sporty gent in blousy knickers and black-and-white wingtips standing and fishing among a medley of canoes, as in “Fishing” (1929), or the giant paper mill at “Mill at Howland” (1926).

You can see camping in the 1920s without a labeled food product in sight, or for that matter, a labeled garment of any kind. In those days, people did not shop for outfits; they used old clothes.

And, more important, you can see many images of the stunning wonder of northern Maine made during a lifetime in which nature seemed in control of its destiny.

As to aesthetics, Call’s images are harmonious and often quite grand. He appears to have waited for the luminous moment, and knew a felicitous congruity when he saw one.

If I were to attempt a classification, I would say this: He moved from the pictorial to what came to be called straight photography. But such inconsequential notions aside, Call was a photographer open to nature without posture or conceit, but influenced, of course, by the attitudes of his times.

It is important to note that the reprinting of old negatives such as Call’s, whether photographically or digitally, is laborious and demands highly developed skills, both technologically and aesthetically.

The reprinting for this event was done by Todd Watts, who also did some of the principal printing for Berenice Abbott. His efforts are inspirational.

This gorgeous exhibition is for everyone.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 47 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.