FALL RIVER, Mass. – He worked in a mill, as so many men did here. He worked as a steamfitter, too. He died in 1969 at 69 years of age.

His name was Frederick L. Mayo, and for 26 months, he was one of the “doughboys,” the boys of the Yankee Division who went to France during World War I.

And he was an artist.

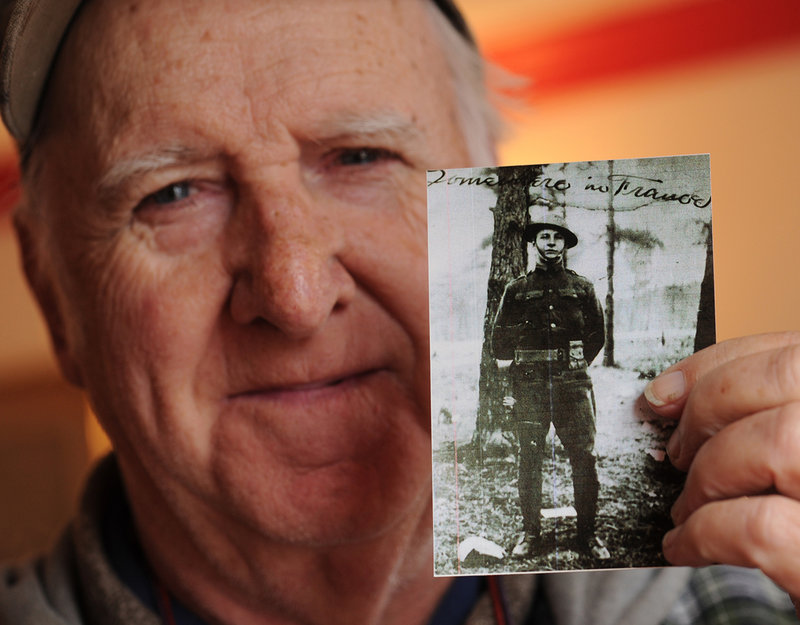

His son, John Mayo, 76, has the drawings his father made as the Americas of the Yankee Division careened about the front, butting bloody heads with the Germans. Frederick Mayo was bayoneted in the arm.

Now the drawings, startling in their energy, are at the Lafayette-Durfee House, 94 Cherry St., where — along with WWI weapons and uniforms belonging to the David Jennings collection — they can be seen for free on Sunday from 1 to 4 p.m. A $3 donation would be appreciated.

“I’d like the kids to see them,” Jennings said of the sketches, which show life on the battlefield.

“He always drew, even when he was a little kid,” John Mayo said of his father. “He told me when they were in the trenches and guys were crapping their pants, he was sketching.”

His family sent him colored pencils, and Frederick Mayo drew it all, sometimes sketching with his feet hanging out of the door of a boxcar, one of many he would ride from battle to battle in his 26 months overseas.

“The officers told him to get rid of his sketches and his diary,” John Mayo said. “They told him if the Germans captured him with them, they’d put him up against a wall and shoot him because there was too much information in there.”

Frederick Mayo kept sketching, rigging up a special mechanism in a pouch he wore to keep a bottle of ink from going dry.

“He had it in a pouch,” John Mayo said. “He had a spring underneath the ink bottle and one on top, so when he ran, the ink would stay liquid.”

And Frederick Mayo ran. He was a liaison runner, running from unit to unit with messages. Liaison runners typically did not have long life spans.

“He saw hell,” John Mayo said of his father. And he didn’t forget.

“He didn’t talk much about it,” John Mayo said recently, his father’s sketches laying on a table. “But when he did, I listened.”

The images are startling. A man crushed by a tank, just his legs peeking from beneath the cruel treads. A German pilot falling from a damaged plane. Men going “over the top,” leaving the trenches for an attack. Pictures of Australian “diggers” and French “poilus” in their uniforms.

Frederick Mayo’s pictures tell the story.

“When we used to go get groceries, my father used to say, ‘God bless America,”‘ John Mayo said. “He said it every time.”

John Mayo asked his father why he uttered this little blessing every time he went to the store.

“I went without food many a time,” came the answer.

And Frederick Mayo made it home, sketches intact, memories still stinging.

“When he saw the Durfee tower, when he was coming home on the train, he sat down and cried because he never thought he’d make it back.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.