When you read a novel, you expect fiction. When you read a memoir, you expect facts. Somewhere between these genres lies a battleground where truth has become the weapon of choice.

Some authors have paid dearly for writing memoirs that were long on embellishment, short on fact. But should novelists be held to the same standard? Or does a novel’s reality, by definition, allow room for invention? And if you believe the substance of a novel, would you feel duped to learn that things weren’t quite as they appeared?

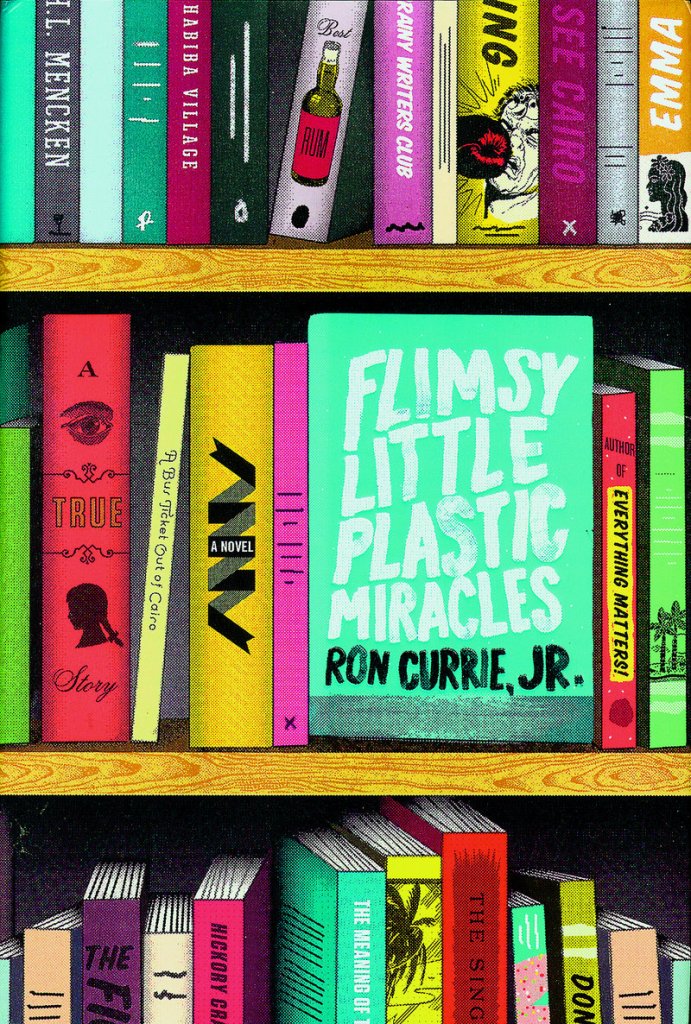

These are some of the questions posed by Ron Currie Jr.’s dazzling and audacious novel, “Flimsy Little Plastic Miracles.” In his metafictional world, Currie pulls out all the stops. His protagonist shares not only the author’s name, but much of his personal bio: Among other things, both are in their late 30s, bearded and bald; each is a novelist and native of Maine.

If inquisitive readers find themselves Googling certain alleged facts in the story, not to worry — that’s exactly how the character, Ron Currie, discovers that his posthumous suicide note has gone viral and his unfinished novel has become a bestseller.

Confused?

Welcome to the house of mirrors that is the book’s central riddle. This is a story about hope and heartbreak, actions and consequences, where the ring of truth often vies with the truth itself. While the book spans two continents and multiple time frames, the narrative reflects the turbulent life of its main character.

Currie’s meditations and longings, his carousing and deceit, are all part of the same puzzle. The story he tells is, by turns, stark, moving and lyrical — and it’s hilarious to boot.

What propels this postmodern novel is the anguished tale of its anti-hero. First, we meet Emma, his ever-elusive sometimes flame, who’s never quite available. Now that she’s getting a divorce, Currie’s prospects would seem to improve. Still, they make a combustible pair, troubled at the core.

“With Emma, her trademark is the distance she creates,” Currie writes. “No one could ever really have her.” Then later: “She doesn’t realize it, I don’t think, but she hides. Sometimes right in front of you. You always find yourself reaching for her an instant too late, and grasping at smoke.”

Furthermore, Currie’s father has recently died of lung cancer. Currie’s bedside dispatches are an elegy of sorts, and one of the book’s stunning achievements.

The loss of his father and the prospect of being “dismantled” yet again by Emma lead Currie to a muddle of despair. He goes on a bender, gets into fights, starts a fling. Then he drives off a pier into the ocean in hopes of ending it all.

That he manages to survive sets in motion a bizarre chain of events — his fake suicide and subsequent disappearance, publication of his unfinished “Emma novel,” media fanfare and more. Meanwhile, our distraught narrator has exiled himself to Egypt for several years, where he seeks nothing so much as the blankness of the desert to mirror the self he hopes to erase.

But erasure is not in the cards. Currie’s faux suicide spawns a host of unintended consequences.

“I would end up needing hours to take in all the ways in which my life had changed since I’d died,” Currie says of Googling his name at a Cairo Internet Cafe. “The suicide note had hit some great neglected nerve and people came to bookstores as if on a pilgrimage.”

Nor does he properly anticipate people’s reactions to news that his suicide was a hoax. Some were furious, demanding refunds of the book’s price; others filed class-action lawsuits.

Above all, when Currie and the newly remarried Emma meet again at a coffee shop in Maine, she slaps him across the mouth, claiming he could have had her in the palm of his hand. Perhaps. As with so much of this inventive tale, Currie reports and readers will decide.

Fact and fiction mingle well in this equal opportunity forum. But ultimately, the degree to which the lives of the author and narrator overlap is beside the point. What matters is that Ron Currie has written an irresistible story, revealing truths as profound and startling as any you’re likely to read.

Joan Silverman of Kennebunk writes op-eds, essays and book reviews for numerous publications.

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.