Through Sept. 8, the Portland Museum of Art will be much more than it usually is. Icons of Modernism have made their way to summer in Maine.

Even if you have never actually seen any of the William S. Paley Collection’s 60 paintings, drawings and sculptures, you will recognize many of them in “A Taste for Modernism.”

From a curatorial standpoint, the show is a fait accompli, because it comprises the collection Paley bequeathed to the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1990. But Paley himself was the lifeblood of MoMA. For more than 50 years, he helped lead the (arguably) most important American museum of all time.

There are various valid filters through which to consider this show, including: One man’s personal art collection; an element of MoMA’s collection; a collection dynamically and inextricably bound to the cultural and institutional growth of MoMA; or simply as individual major works of art.

From its start, MoMA adopted a polemically linear approach to its presentation of Modern art. The art was hung in rooms with a single direction through which visitors had to flow. It had a theory, and it sought to persuade. And, boy, did MoMA work its magic on American culture.

MoMA’s history can explain some apparent anomalies in the PMA show, such as the distortedly discomfiting 1962-63 Francis Bacon triptychs. (I remember the trio of gold-framed Bacons on MoMA’s first floor in the 1980s.)

However, the collection is so overwhelmingly strong that it’s almost impossible not to get caught up in individual or small groups of works.

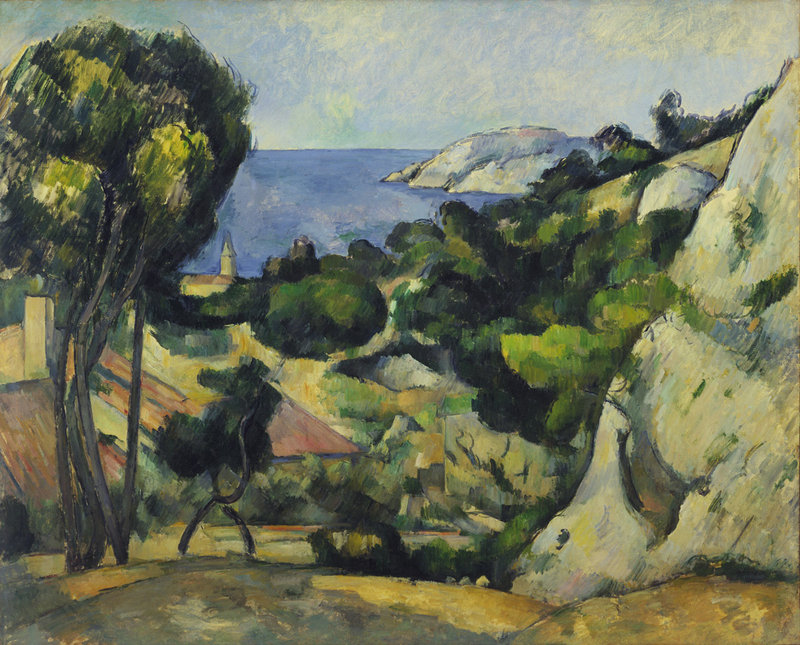

The first thing you see just might change how you understand Maine coastal painting. Paul Cezanne’s “L’Estaque” (1879-83) is not only a masterpiece, it was owned by Claude Monet. It is quintessential Cezanne — an unusual but serenely structured and value-attenuated whole painted with forcefully staccato but rhythmic pulses of brushwork that intertwine both spatially and as surface. (I suggest looking to the pink triangle in the lower center next to a flat, vertical rectangle to consider what they are doing there.)

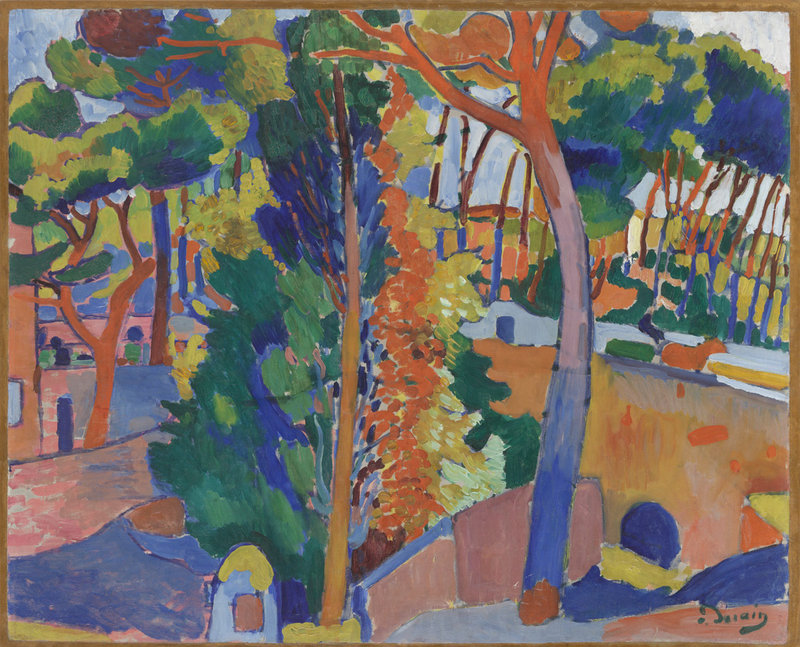

The first room echoes MoMA’s original didacticism by facing off Gauguin’s masterwork “Seed of Areoi” (1892) opposite one of the greatest Fauvist canvases, Andre Derain’s “Bridge over the Riou” (1906). Together, they make the case that Gauguin’s indulgently vivid palette helped spawn Fauvism, but in truth, they reveal the brilliance of each other.

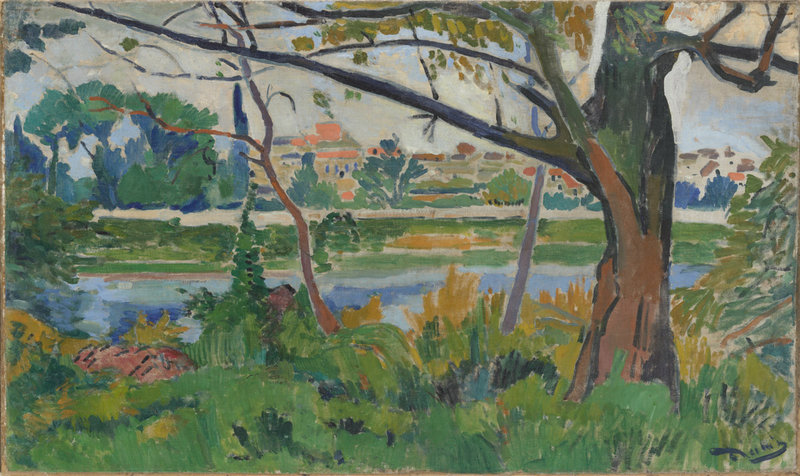

Derain’s Fauvist-era work has always been my favorite representational painting. While the “Bridge” is a coloristic triumph, Derain’s “Seine at Chatou” (1906) is a structural and compositional tour de force. By following a startlingly long and straight tree branch visually through the far space and sky across the river, Derain mobilizes elegantly subtle geometry to enter the space from the painting’s surface.

Conversely, Derain’s 1933 “The Rehearsal” is the show’s enfant terrible. The bleak and bleary depiction of two classically draped actors gesticulating theatrically was unfinished when Paley visited the artist’s studio and no doubt bought it through pity or pressure. (That Paley later persuaded Derain to finish it hints that Paley never particularly liked it.)

MoMA’s story of Modernism resembles a tree beginning with Cezanne as the trunk and then branching out with Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Picasso, Matisse and so on. This is also the narrative of the Paley Collection and its handsome installation by the PMA’s Margaret Burgess.

The most powerful presence is Picasso. His blue/rose “Boy Leading a Horse” (1905-06) is a work of brilliance on a scale we associate with tableaux. But its genuinely sensitive humility is largely betrayed by what we can no longer see.

This work would have appeared as a cartoon — a preparatory work to scale not even pretending to be a finished painting. That would explain the simplified forms and drawing.

But in Picasso’s hands, the classical references, nudity, economy — and poverty — come together with subversive brilliance to dismiss the academic status quo. And like his clothes, Picasso reveals the emperor’s new reins.

Overshadowed somewhat by the larger work is the greatest piece of the collection, Picasso’s “Architect’s Table” (1912) — the very apogee of Analytic Cubism.

Placement and lighting certainly matter in this show, and it’s important to remember that Picasso’s (and all other) drawings aren’t brightly lit in order to preserve them.

Still, light and color are the main reason no one should miss this show. No photograph could capture the subtle color (density, transparency, reflection, juxtaposition, saturation, etc.) of Matisse’s gorgeous “Musketeer” (1903). Nor could it reveal the reworking of his Nice period “Seated Woman with Amaryllis” (1941) that’s visible (in person) in her flesh-and-yellow dress.

While Matisse’s paintings look fresh and spontaneous, they are anything but. The artist worked them for months until he was satisfied.

There are too many great works to list, let alone discuss.

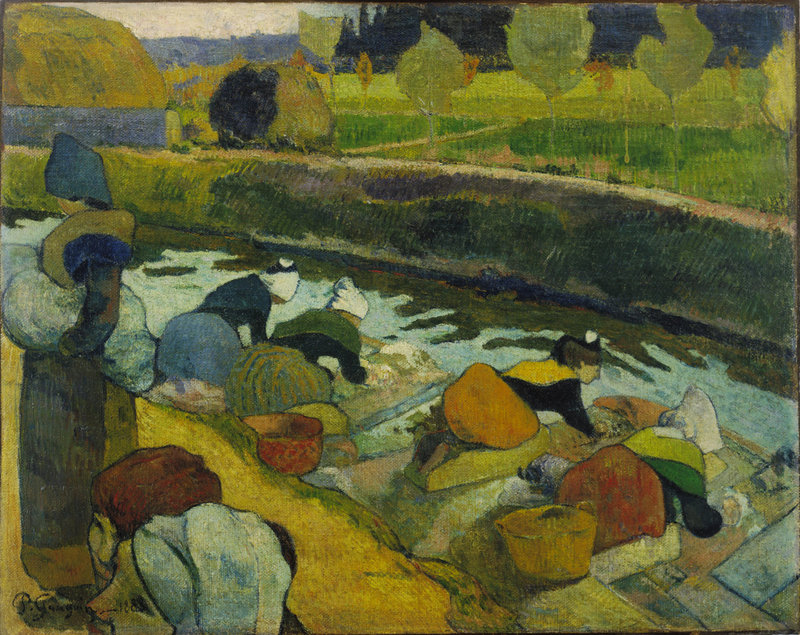

My favorites include Cezanne’s drawing of his wife; Giacometti’s painting “Annette” (I like his paintings even more than his sculpture); Gauguin’s “Washwomen,” painted in the company of Van Gogh, who gushed about it in letters to his brother; a pair of great Toulouse-Lautrec portraits; Maillol’s terra cotta seated nude, beautifully placed in front of a weird/beloved Rose Period Picasso nude and drawings; Rodin’s pedestal-scaled “Burghers of Calais” (Paley’s sculptures are small but strong); Manet’s tragically late pair of creamy roses; and a smattering of exquisite Nabi interior scenes.

Although they don’t even make the show’s short list, the works by Degas, Renoir, Hopper, Rouault and Braque would lead the PMA’s collection.

Featuring the work underlying the great Maine art of Hartley, Marin, Nevelson, Hopper, Homer, Kuniyoshi and so many others, the Paley Collection shows up particularly well at the PMA.

We are the beneficiaries of Paley’s insistence that his collection travel to 20 venues. The PMA is the 18th stop, and the only in New England. After the collection goes to Arkansas and Quebec, most of it may never travel again.

So don’t miss it now.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.